The Early Elvis Presley Movie: Star as Genre

Will Scheibel

“That ain’t tactics, honey. It’s just the beast in me.”

– Elvis Presley, Jailhouse Rock (1957)

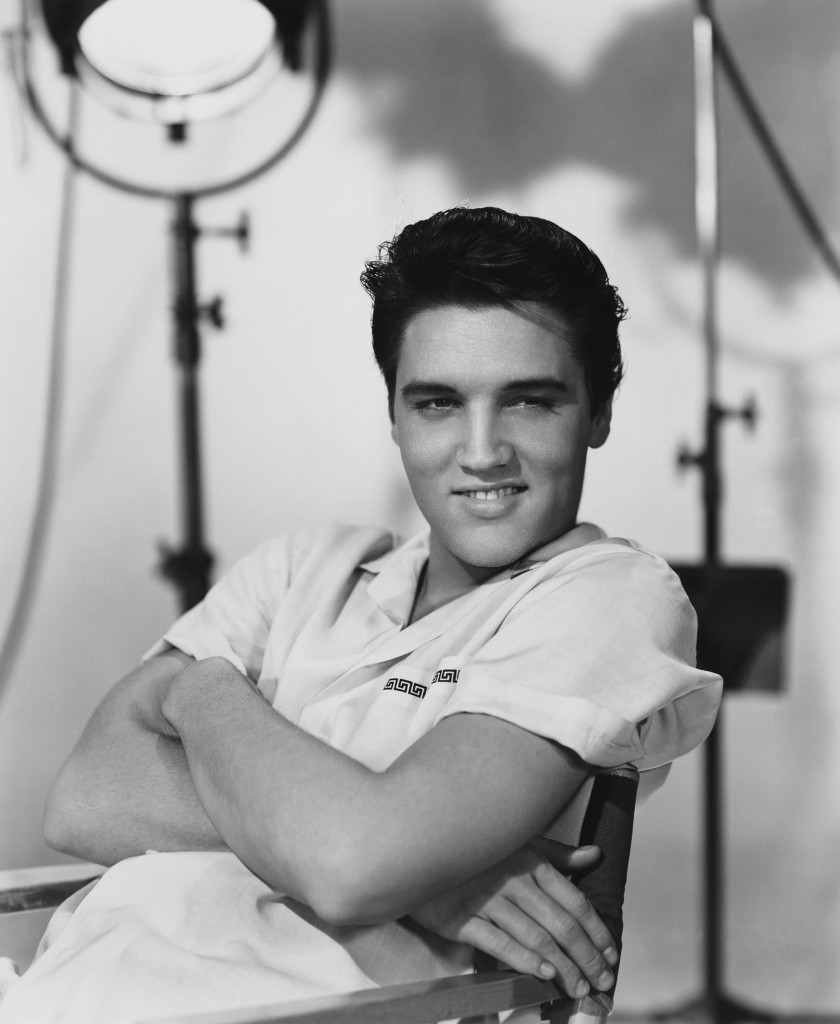

Perhaps more than any other Hollywood star of the 1950s and 1960s, Elvis Presley was burdened with a reputation up to which he could never live. RCA Victor released his self-titled debut studio album, now a fixture of rock-and-roll lore, in March of 1956. Movies immediately followed and formed a genre unto themselves: the “Elvis Movie.”

Critically maligned and often blamed for ruining Presley as a serious artist, the association of these films with bad taste is so prevalent that one is likely to forget Presley’s different course as a star in those first years with the films Jailhouse Rock (1957), King Creole (1958), Flaming Star (1960) and Wild in the Country (1961). Presley was angrier, the films were darker, and the music was dirtier. I do not present a new theory of stardom, genre, or Elvis movies in this short piece, but I hope to begin a more nuanced, rigorous analysis of Presley’s movie career, the subject of old assumptions and generalizations (and also little scholarly attention). Further, I want to introduce some preliminary thoughts about the kind of genre function a star serves, and how the cultural production of genres may adapt to the evolution of particular star images and performance styles, thus producing new conventions, expectations, and discursive fields based specifically on the actor.

Presley’s early film roles came on the heels of young male Method actors such as James Dean, Marlon Brando, and Montgomery Clift, announcing him as a cool 1950s rebel-type. In Love Me Tender, a 20th Century Fox Western released in November of 1956, Presley co-starred with Richard Egan and Debra Paget (henceforth he always received top-billing). Originally called The Reno Brothers, the film underwent a title change to capitalize on the popularity of Presley’s single “Love Me Tender” written for the soundtrack. Presley was particularly excited to meet the film’s producer David Weisbart, who had just produced the James Dean hit Rebel Without a Cause (1955) for Warner Bros., reportedly Presley’s favorite film, and was planning a bio-pic on the late Dean, in which Presley expressed enthusiastic interest.[1]

Record producer Sam Phillips, the founder of Sun Studios and Sun Records in Memphis, where he discovered Presley, predicted that he would go on in Hollywood to become another Dean. Talking to celebrity columnist Lloyd Shearer of the Sunday Parade, Presley spoke of the ways in which he and Dean both personified the figure of the rebel:

I’ve made a study of poor Jimmy Dean. I’ve made a study of myself, and I know why girls, at least the young ‘uns, go for us. We’re sullen, we’re broodin’, we’re something of a menace. I don’t understand it exactly, but that’s what girls like in men. I don’t know anything about Hollywood, but I know you can’t be sexy if you smile. You can’t be a rebel if you grin.[2]

Presley actively cultivated this image during the 1950s, and actually modeled himself after Dean, reflecting his sullen, brooding demeanor, but also his vulnerable masculinity, what Presley’s foremost biographer Peter Guralnick described as “a kind of scornful pity, indifference, a pained acceptance of all the dreary details of square reality.”[3]

The director of Rebel Without a Cause, Nicholas Ray, also saw Presley as another Dean. Ray wanted to cast him in the title role of his upcoming film at Fox, The True Story of Jesse James (1957) (it eventually went to contract player Robert Wagner).[4] Upon meeting Presley, Ray remarked, “he got down on his knees before me and began to recite whole pages from the script. Elvis must have seen Rebel a dozen times by then and remembered every one of Jimmy’s lines.”[5] Independent producer Hal B. Wallis was yet another member of the entertainment industry who viewed Presley as a successor to Dean, essentially contracting him on the basis of his first national television appearance on CBS-TV’s Stage Show in 1956.[6] More significantly, Wallis approached Presley as a direct line into the new American youth market of the 1950s.[7]

After his loan-out to Fox for Love Me Tender, Loving You (1957) was Presley’s second film and the first of nine vehicles Hal Wallis Productions made for him over the next ten years, which Paramount Pictures distributed. Presley’s career in Hollywood lasted until 1969, during which time he acted in thirty-one films and worked with a range of producers and directors. However, it was Wallis who transformed Presley into a movie star. Wallis sensed that Presley had the charisma, talent, and good looks to carry a film, but he also felt the public would only accept him as a singer first and an actor second.[8]

The turning point was Presley’s return from the Army with the Norman Taurog-directed Wallis productions G.I. Blues (1960) and Blue Hawaii (1961), both developed in line with Wallis’s ideas about Presley and both box-office smashes (the Blue Hawaii soundtrack spent twenty consecutive weeks at number one on Billboard’s top album chart, ranking as his most successful record). What proceeded from these two films was a near decade-long string of low budget, quickly made, and highly profitable musical-comedies that comprised something of an exploitation cycle in the 1960s. Presley was recast from a surly, backwoods bad boy to an all-American boy-next-door from the country, with barely a hint of the sensual “beast” that lurked in his juvenile delinquents from Jailhouse Rock, King Creole, and Wild in the Country. The banal, recycled formulas were built entirely around contrived excuses for him to sing songs to sell soundtracks, towards which all of his musical efforts were exclusively dedicated at the time. To Presley’s embittered disillusionment, and at the height of his movie celebrity, he realized he would not be able to demonstrate his full potential as an actor in the Wallis mold.[9]

Although Presley’s charms were well suited for this lightweight fare, most of these films offered him little to work with beyond admittedly bland and forgettable musical numbers. For example, G.I. Blues features eleven songs and Blue Hawaii boasts fourteen, while in the musicals Loving You and Jailhouse Rock, Presley sings only seven and six songs, respectively. Produced by the independent company Avon Productions and distributed by MGM, Jailhouse Rock nevertheless gave Presley one of his most famous soundtracks, courtesy of songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Flaming Star, a liberal Western directed by action auteur Don Siegel, and Wild in the Country, a family melodrama written by social realist scribe Clifford Odets, were also made outside of Wallis’s control at Fox. Presley sings one song in the former film and five songs in the latter film, in addition to the title songs in both, which proved commercially disappointing after G.I. Blues.

The atypical, noiresque outing Wallis produced for Presley, King Creole, was directed by Michael Curtiz, a Hollywood veteran who knew Wallis from their old days at Warner Bros. in the 1930s and 1940s (Presley considered it his favorite of all of his films). Like Loving You and Jailhouse Rock, King Creole thematizes Presley’s rise to stardom. The musical numbers in all three films are narratively integrated and diegetically motivated, justified by Presley’s characters. Deke Rivers, the hero of Loving You, is a delivery man who gets his big break as a singer with the help of a female publicist and a fading country musician, while Danny Fisher, the high school student with a golden voice in King Creole, is vied over by rival club owners in the mob-run French Quarter of New Orleans.

Presley seemed never more natural or comfortable as an actor than in King Creole or Jailhouse Rock, playing a cocky, sneering self, whose musical energy and volcanic sexuality are as raw as exposed nerves, the affective force of which has rarely been matched by a singer in a film. As Vince Everett in Jailhouse Rock, an ex-convict jailed for accidentally killing a man in a bar fight, Presley becomes a musical sensation through the teachings of his cellmate, a washed-up country singer. When he is released, he starts his own record label with a female promoter and eventually signs a deal with a movie studio (Loving You was clearly an influence, but the film also works to align Presley with Dean’s image as an alienated non-conformist). Presley sings to diegetic audiences in prison, where one of his performances is broadcast on television, as well as at a club, a recording studio, and a Hollywood party. Throughout the film, Presley’s band appears as back-up with Stoller on the piano. Yet, these songs are often uncompleted or interrupted. The film forces us to wait until the eponymous set piece for its proper full-blown number, a television special inspired by Vince’s experience in prison, which brings euphoric relief from delayed gratification—for Vince, too, whose fire and passion is unleashed via Presley.

Jailhouse Rock could be interpreted as an attempt to translate Presley’s musical performance ethos into cinematic terms. In his classic book Mystery Train, rock-and-roll historian Greil Marcus argues, “Elvis sang with contempt for a world that has always excluded him; he sang with a wish for its pleasures and status. Most of all he sang with delight at the power that fame and musical force gave him: power to escape the humiliating obscurity of the life he knew, and power to sneer at the classy world that was ready to flatter him.”[10] The desperate pleas behind “Don’t Leave Me Now” and “Treat Me Nice” underscore Presley’s outsider status with earnestness, while his wailing of “I Want to Break Free” articulates a painful cry of existential isolation. On the other hand, “Jailhouse Rock” represents not only anti-authoritarian protest and institutional defiance, including a liberation of the body from utilitarian function into pure, expressive gesture, but also the sheer exuberance with which Presley enjoyed performing—to say nothing of the newfound fame he equally enjoyed. After losing his voice (i.e., potency) when his values are corrupted by Hollywood, the film finally requires Presley to sing the sensitive love song “Young and Beautiful” in order for Vince to regain his integrity and his control over his surroundings.

Presley’s musical performances in his movies promoted his star image at the intersections of music and film, synergistically defining an audience for him across both media. Once Wallis established a system for the Elvis movie, Presley’s films were at the service of their readymade soundtracks. Between 1956 and 1961, though, his earlier films either reduced musical numbers to a minimum to foreground Presley as a musician-turned-actor, or strategically deployed them as a structural device in the “making” of Elvis Presley onscreen that enabled his offscreen stardom.

Will Scheibel teaches at Indiana University, where in May 2014 he will defend his Ph.D. dissertation in Film & Media Studies. He is the co-editor, with Steven Rybin, of Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground: Nicholas Ray in American Cinema (SUNY Press, 2014) and is currently writing a book on Ray’s reputation. He has also written articles for The Journal of Gender Studies, Oxford Bibliographies, Celebrity Studies, and La Furia Umana.

[1] Peter Guralnick, Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1994), 243, 327. Weisbart also produced three more Elvis movies: Flaming Star, Follow That Dream (1962), and Kid Galahad (1962).

[2] Ibid., 323-324.

[3] Peter Guralnick, Lost Highway: Journeys & Arrivals of American Musicians (Edinburgh: Canongate, 2002), 118-119.

[4] Bernard Eisenschitz, Nicholas Ray: An American Journey, trans. Tom Milne (London: Faber & Faber, 1993), 283-284.

[5] Quoted in Guralnick, Lost Highway, 119. For an illuminating discussion of the ways in which Ray’s films resonate with Presley’s musical performances, see Paul Anthony Johnson, “‘You Can’t Be a Rebel If You Grin’: Masculinity, Performance, and Anxiety in 1950s Rock-and-Roll and the Films of Nicholas Ray,” in Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground: Nicholas Ray in American Cinema, ed. Steven Rybin and Will Scheibel (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2014), 139-149.

[6] Bernard F. Dick, Hal Wallis: Producer to the Stars (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2004), 159-160.

[7] Guralnick, Last Train to Memphis, 260.

[8] Dick, Hal Wallis, 160.

[9] Peter Guralnick, Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1999), 171.

[10] Greil Marcus, Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music, 4th revised edition (New York: Plume, 1997), 160.