Teaching Inception

John Bruns

The gateway course for the Film Studies program here at the College of Charleston is ENGL 212: “Cinema: History & Criticism.” The course is historical, although I do not teach it in an exclusively chronological way. Yet I always begin the course with a discussion of early film spectatorship, assigning Tom Gunning’s essay “The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator, and the Avant-Garde,” and we end the course with a discussion of the rise of digital cinema, supplemented by a screening of Christopher Nolan’s 2010 film, Inception and the first chapter from D.N. Rodowick’s The Virtual Life of Film (which is also entitled “The Virtual Life of Film”).[1] In many ways, the discussion of digital cinema allows us to return to concepts dealt with at the beginning of the class, and indeed throughout the semester. Primarily, we return to the question of film’s ontological status—a status that is, quite frankly, understood as a given throughout most the semester: this thing we call “film” is rooted in photography. One of the first pieces of film theory I assign my students is the excerpt of Siegfried Kracauer’s Theory of Film reprinted in the Oxford U. Press anthology, Film Theory & Criticism, entitled “Basic Concepts.” In it, Kracauer argues that the basic property of film is photography: “Film, in other words, is uniquely equipped to record and reveal physical reality and, hence, gravitates toward it.”[2] It is not until we arrive at the end of film that we confront this claim head-on.

What is the end of film? I pose this question to my students and add that, for the duration of this final, week-long unit (which reads, in my syllabus, simply as “Digital Cinema”) we will attempt not only to answer the question but see to what extent the question is loaded, perhaps over-loaded. If one were seeking a clear and precise answer to the question, one might first mark the date when film dies (or began to die). An obituary of sorts was run in the Los Angeles Times on June 18, 1999:

Starting today, the Force will be with digital cinema for the next four weeks as audiences in Los Angeles get their first glimpse of moviegoing of the future…Through July 15, The Phantom Menace will be shown digitally on one screen at AMC’s Burbank 14 theater and on another at Pacific’s Winnetka theater…The experiment marks the first commercial digital presentation of a full-length feature film. It also heralds a competition among companies with rival technologies and business models.[3]

I then indicate that this report of film’s death is greatly exaggerated (cue Monty Python & the Holy Grail reference: “I’m not dead yet!”). Nevertheless, by May of last year (according to the National Association of Theatre Owners) 37,711 out of 40,048 movie theatres (or approximately 94% of all theatres) have been converted to digital.

I find that “The Virtual Life of Film” is a useful supplement to our discussion of Inception because, although Rodowick’s book came out a few years before Christopher Nolan’s mind-bending film, it deals with films that, like Inception, depict a struggle between a virtual world and the real world. Although Rodowick mentions in passing Dark City, Thirteenth Floor, and eXistenZ, the film that, for him, best illustrates what he calls “the allegorical conflict between the digital and the analog” is the Wachowski brothers’ 1999 film The Matrix.[4] Released the same year that Hollywood introduced, in Los Angeles but in New Jersey as well, digital screenings of The Phantom Menace, Rodowick sees a connection between The Matrix’s nightmare battle between virtual and real as an allegory for the rise of digital cinema and the resulting “death” or disappearance of film:

The Matrix is a marvelous example of how Hollywood has always responded ideologically to the appearance of new technologies. Incorporated into the film at the levels of both its technology of representation and its narrative structure, the new arrival is simultaneously demonized and deified, a strategy that lends itself well to marketing and spectacle.[5]

One of the ways I elaborate on Rodowick’s point about Hollywood’s ideological responses to new technology is by reminding my students of the previous week’s discussion, in which we looked at the rise of television in the 1950s. A more useful approach is briefly to touch on Victor Fleming’s 1939 film The Wizard of Oz. Everyone familiar with the film (and most of my students are) knows that the film magically transforms from black and white to full color at precisely the moment the Land of Oz is revealed to Dorothy (Judy Garland), and to us, for the first time.

The film celebrates, or, to use Rodowick’s term, “deifies” the relatively new technology (in this case, the three-strip Technicolor process) by coloring Oz so it looks like the wonderful, magical, “over the rainbow” place Dorothy has been dreaming of (and singing about). Yet at the level of narrative, the film simultaneously demonizes this imaginary world (which is haunted by cranky talking trees, blanketed above by creepy flying monkeys, ruled by a frightening, extortionist wizard, and terrorized by the Wicked Witch of the West) by making Dorothy’s desire to return home more and more urgent. When Dorothy is safely home, in the “real” world, the film reverts back to the more familiar (and comforting) black and white stock. The film’s famous coda is “There’s no place like home.” Why? Because home is real, and everything else is new, virtual, and frightening—but also visually spectacular.

The point here is that, of course, Dorothy’s “home” is no more real than Oz. Both are studio constructs, photographed fictions, projected illusions—or to put it another way, Kansas is just as virtual as Oz. Nevertheless, as Rodowick argues, by staging a dramatic opposition between two different narrative registers, one real and one imagined, “Hollywood narrative, even in its most outlandish form, asserts all the more stridently its status as ‘reality.’”[6] Note the way Dorothy, in The Wizard of Oz (which is certainly an outlandish form of Hollywood narrative), repeats, literally, the film’s ideological project: “There’s no place like home….there’s no place like home…there’s no place like home.” The phrase becomes a mantra; simply by asserting it, over and over again, “home” claims the status of the real. It’s the very ticket that gives Dorothy access out of the virtual and into her bed, safe and sound and surrounded by loved ones.

Today, the “new” that Hollywood is coming to terms with is digital technology. But it’s been a long time coming. And here is where I lead students through a brief timeline of digital imaging in Hollywood narrative film—one that is borrowed partly from Rodowick and partly from chapter 21 of David Cook’s History of Narrative Film, 4th ed.[7] I begin with a clip from Futureworld (dir. Richard Heffron, 1976), which is the first mainstream feature film that has a three-dimensional computer generated image in it. Then I show them a brief featurette about the making of the “Genesis sequence” from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (dir. Nicholas Meyer, 1982), which utilizes composite imaging and an effect known as “motion blur,” which is meant to simulate the blurring caused by the shutter in analog motion picture photography. Young Sherlock Holmes (dir. Barry Levinson, 1985) is next. This film lays claim to the first three-dimensional computer generated character—a medieval knight that leaps from the stained glass window of a church. A clip from Ron Howard’s 1988 film Willow demonstrates the CGI effect of “morphing”—where one computer generated image “morphs” into another. The timeline takes us up to the 1999 release of The Matrix, and back to Rodowick.

The so-called allegorical narrative conflict between digital and analog plays into Hollywood’s interests in two ways. On the one hand, something “new” can be marketed: spectacular computer generated imaging (CGI). The key player here is George Lucas’s special effects company Industrial Light and Magic, formed in the 1970s, which has contributed effects for something around 320 films and has garnered 19 Academy Awards.[8] More than any other company, ILM has defined cinema in the digital era. But as I am suggesting here, and what makes Christopher Nolan’s Inception such a useful film when discussing the arrival of the digital era, is that this definition of “cinema in the digital era” is extraordinarily complex. The promotional blurb for a new documentary about ILM, Industrial Light & Magic: Creating the Impossible (dir. Leslie Iwerks, 2015) states:

The digital era that dominates modern day visual effects was ushered in by ILM, and through the years ILM has given filmmakers the means to achieve anything. Photorealistic characters and fantastic worlds can be created from scratch, such as on Terminator 2, Jurassic Park, Pirates of the Caribbean, Iron Man and Avatar.[9]

What the above blurb reveals is the way in which photography and realism continue to play vital roles in today’s digital era. So on the one hand, film (“the mechanical recording of images through the registration of reflected light on a photosensitive chemical surface”) is regarded as “the sign of a vanishing referent,” the warm medium to which only a few pure purists continue to cling.[10] Even among these purists, these filmmakers who prefer to shoot with film, many see the wisdom in working exclusively with digital video (this is because a celluloid image, when transferred to digital and then projected digitally, loses considerable quality).

On the other hand, as the above blurb indicates, “photorealism” remains the touchstone of digital imaging. Take, for example, the effect of motion blur, which I demonstrate with the clip from the Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan documentary. The point of motion blur is to simulate photographic realism, to achieve an optical flaw unique to celluloid filmmaking. Digital imaging can indeed create “fantastic worlds” and, as Rodowick concedes, experiments in digital imaging have given us many stylistic innovations. But by and large, these “fantastic worlds” adhere to the same conventions of pictorial representation that we’ve been using since the Quattrocento. As Rodowick puts it, there is a strong sense in which what counts intuitively as an “image” has changed very little for Western cultures for several centuries. Indeed, there is much to be learned from the fact that “photographic” realism remains the Holy Grail of digital imaging. If the digital is such a revolutionary process of image making, why is its technological and aesthetic goal to become perceptually indiscernible from an earlier mode of image production?[11]

The answer Rodowick offers is an intriguing one, and it is an answer that Inception helps to illustrate. My students are well prepared to engage in a discussion of this very pointed question, using Nolan’s film. Well prepared because they have already been introduced to the films and ideas of the French New Wave, particularly the work of Jean-Luc Godard. To be sure, throughout the course of the semester, no other filmmaker has been more adamant about challenging our inherited notion of “photographic realism,” and here is where my students are challenged to do some serious synthetic thinking. Godard’s films persistently undermine narrative absorption by calling attention—through direct address, jump cuts, and disruptive use of soundtrack and intertitles, to name but a few of his techniques—to the artificiality of the photographic image. Here an oft-quoted line from Godard is useful: “Cinema is not a reflection of reality, but the reality of that reflection.”[12] It’s the sort of mind-puzzle that fans of Christopher Nolan’s films appreciate, and it becomes the springboard to a full-on discussion of Inception and its place within our current “digital era”—specifically, the popularity of what Rodowick calls the allegorical narrative conflict of digital versus analog, and the ways in which this narrative conflict works to camouflage the imaginary status of the photographic image.[13]

What makes Inception different from many of the films Rodowick cites (and to which we might add dozens of other films, such as Avatar—which actually reverses the values in Rodowick’s allegorical narrative conflict, making the imagined, “digital” world superior both aesthetically and morally) is that Christopher Nolan chose to use as few digital effects as possible, relying instead on what are commonly known as “practical effects.” More interestingly, Inception was shot using anamorphic 35mm, with a few sequences shot in 65mm. Nolan, like other filmmakers such as Paul Thomas Anderson and Quentin Tarantino, prefers and continues to work with celluloid film. What makes Nolan stand out, here, is that his films are known for staging variations of the narrative conflict—understood more broadly, perhaps, as “real versus imagined.” More importantly, as Todd McGowan shows in his book The Fictional Christopher Nolan, Nolan’s films “intervene on the larger question of creation itself.”[14] Although McGowan is here speaking of The Prestige, the statement may apply to many if not all of Nolan’s films. Indeed, McGowan argues that Inception actually exposes our misguided faith in reality and, in doing so, privileges the dream, the illusion, over reality.[15]

The path to such a conclusion is as tangled as a Christopher Nolan plot. But most students are prepared to think critically about Inception and its status within the “digital era” specifically, and its status as “cinema” generally—and there is no way the two can be separated. One cannot, perhaps should not, reflect on the state and direction of digital cinema without also reflecting on the very nature of the medium. And there is, to my mind, no better film to use to get students to synthesize the material covered in the course in order to do just this. Students who love Inception love it more than I do, and I’m a big fan. Students who have seen the film many times have seen it many more times than I, and I’ve taught it regularly since its release. And students are eager to interrogate the film’s ostensible narrative trajectory: to get Dominick “Dom” Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) back home. But is Cobb Dorothy? And is Inception The Wizard of Oz?

While McGowan focuses on the relationship between Cobb and Mal, and the significance and status of the top—the totem, originally belonging to his wife Mal, which enables Cobb to distinguish dream from reality—I ask my students to think about the role of Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy). Initially, Cobb is caught trying to steal secrets (or engage in dream “extraction”) from Saito, head of Proclus Global and rival of the energy conglomerate Fischer Morrow, founded and headed by Robert’s dying father, Maurice Fischer (Pete Postlethwaite). Saito then makes a deal with Cobb: he will use his powerful influence to clear Cobb of any responsibility for his wife’s death, which will allow Cobb to be reunited with his two children. In exchange, Cobb will attempt a heist, an unprecedented act of “inception”: infiltrate Robert Fischer’s dreams and plant a memory that will make him want to break up Fischer Morrow. As spectators, we root for Cobb as he leads his team deep into Fischer’s subconscious, one fortified with militarized “projections” whose sole purpose is to protect Fischer’s subconscious from extractors. What makes this act of inception so urgent is our faith in Cobb’s innocence (he is responsible for Mal’s death, but not criminally so) and his desire to be reunited with his children. But the success of this act of inception hinges on Robert Fischer, and whether or not he responds favorably to the planted memory. And this is what makes Inception so fascinating.

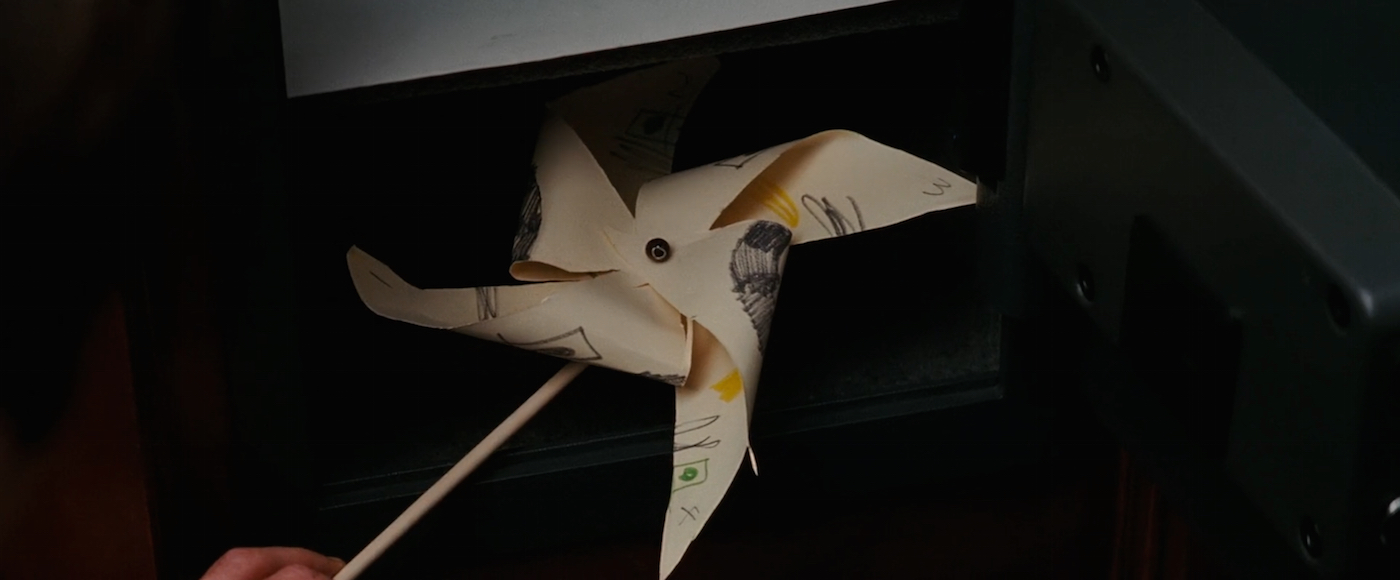

The “plant” is a child’s homemade pinwheel, which Robert finds in a safe next to his father’s deathbed. The first time we see the pinwheel is in photograph of Robert, as a young boy, blowing into the pinwheel with his father’s arms around him [Fig. 1]. This photograph, we learn, captures a cherished moment in Robert’s life, one of the few happy memories—if not the only happy memory—of his father. Early in the film, we see Robert standing by a window in his father’s office, which has been converted, in part, into a hospice. Maurice Fischer’s chief legal counsel and Robert’s godfather (Robert refers to him as “Uncle Peter”), Peter Browning (Tom Berenger), enters the room to ask to speak with Maurice. The camera pans right to reveal Maurice, in bed and heavily sedated, agitated and speaking incoherently, “Robert, I told you to get out the damn—Wait! So do it! Get…Put it through! Never! Never, never do the same as I asked!” Just as Maurice begins shouting these unloving and confused demands at his son, his arm swings violently to his right and sends a framed photograph sailing off the table and crashing to the floor. It is the photograph of Robert, pinwheel in hand, embraced by his father. Robert picks it up off the floor. In close-up, we see the photograph, its glass frame shattered, in Robert’s hands as we hear Peter say, “Must be a cherished memory of his,” to which Robert responds, in the next shot, “I put it beside his bed. He hasn’t even noticed.”

In this way, the film Inception pivots on the importance of the photographic image. More importantly, it poses the question about its status as “real.” And in doing so, poses the very same question about the photographic image in general. To ensure the success of this act of inception, Robert must be moved by the pinwheel he finds in his father’s safe—so much so that he is convinced of his father’s love for him, convinced that his father was not disappointed in him but disappointed that he tried to be like him, convinced that his father’s final wish is for Robert to break up Fischer Morrow [Fig. 2 and 3].[16] Of course this pinwheel is not real, as we are deep within Robert’s subconscious. In fact, we are (as everyone knows, including those unfamiliar with the film) in a dream within a dream within a dream. What empowers this object is its status as referent to the image in the photograph, thus reversing the conventional way in which we associate a real image with the photographic image. This is the film’s greatest switcheroo: the photographic image’s status as the “real” is Inception’s biggest, most beautiful lie.

In his chapter on Nolan’s film, McGowan writes,

There is a truth in Inception, but one discovers it not in reality but in the dream. Like all of Nolan’s films, Inception reveals the fiction—or here, the dream—as the path to this truth rather than as a barrier to it. The insistence on the real world as a separate realm from that of the dream is the film’s primary deception, and one must work through this deception to grasp its privileging of the dream world. Nolan demonstrates that waking up serves as a path for escaping the truth, not finding it.[17]

One might put the matter this way: Inception helps us understand how, like Robert Fischer, we are all dupes. But this truth comes to us as, or through, the lie: elsewhere McGowan states “This deception is necessary for the film because Nolan realizes that one cannot simply tell the truth about the primacy of the lie.”[18] Too many films, according to McGowan, “fail to lie enough” in their efforts to expose the truth. In this way, McGowan’s view of Christopher Nolan is similar to Godard’s view of Georges Méliès. In a famous sequence from La Chinoise (1967), Guillaume (Jean-Pierre Léaud) takes on the role of lecturer and leads his fellow students through a discussion of the films of Méliès and those of Lumière, and it is a scene well worth showing students during this discussion of Nolan’s film. Guillaume begins, “They say Lumière invented current events. He made documentaries. But there was also Méliès, who made fiction. He was a dreamer filming fantasies. I think just the opposite.” His incredulous comrades, in unison, shout, “Prove it!”

Guillaume: Two days ago I saw a film by Mr. Langlois, the director of the Cinémathèque, about Lumière. It proves Lumière was a painter. He filmed the same things painters were painting at that time, men like Charo, Manet, or Renoir…He filmed train stations, he filmed public gardens, workers going home, men playing cards. He filmed trams.

Veronique: One of the last great impressionists?

Guillaume: Exactly, a contemporary of Proust.

Henri: So, Méliès did the same thing!

Guillaume: No, what was Méliès doing at that time? He filmed a trip to the moon. Méliès filmed the King of Yugoslavia’s visit to President Fallières. And now in perspective, we realize those were the current events. No kidding, it’s true. He made current events. They were re-enacted, all right. Yet they were the real events. I’d even say Méliès was like Brecht. We mustn’t forget that. And why mustn’t we? Why mustn’t we? So why?

This last question is met with a prolonged silence, as Guillame’s comrades are flummoxed. It is here that I stop the clip from Godard’s film and turn the question to my students. Why is it important we not forget that Méliès made newsreels? This is not an easy question, but Inception provides students with a useful context in which to search for answers.

That Christopher Nolan continues to prefer shooting his films with 35mm and 65mm film (he angered many theatre chain owners by insisting that his 2014 film Interstellar be screened in 35mm film and 75mm IMAX as well as 4K digital and IMAX digital) might seem to reassert (like so many recent Hollywood narratives) that photography is “the sign of a vanishing referent,” a purer medium than its digital counterpart, more “real.” But students who engage with Rodowick’s argument are able to use Inception in order to question this received wisdom, and, more broadly, to fully appreciate the question posed by André Bazin decades ago: “What is cinema?”

John Bruns is an Associate Professor of English and Director of Film Studies at the College of Charleston. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Southern California and is the author of Loopholes: Reading Comically. His film articles have appeared in Hitchcock Annual, Film Criticism, and New Review of Film & Television Studies.

Notes

[1] David Cook. A History of Narrative Film, 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2003. Tom Gunning. “The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde.” Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative. Ed. Thomas Elsaesser. London: BFI Publishing, 1990. 56-62.

[2] “Basic Concepts: from Theory of Film.” Film Theory and Criticism, 7th ed. Ed. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. 144.

[3] Bill Desowitz. “L.A. Film Fans Preview New Digital Projection.” Los Angeles Times. 18 June 1999.

[4] Rodowick, D.N. The Virtual Life of Film. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007. 5.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] David Cook. A History of Narrative Film, 4th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2003.

[8] Marco della Cava. “Lucas on 40 Years of ‘Star Wars,’ ILM.” USA Today. 14 June 2015.

[9] “Industrial Light & Magic: Creating the Impossible and the Empire Strikes Back.” School of Cinematic Arts Events. Accessed November 4, 2015. http:www.cinema.usc.edu/events.

[10] Rodowick, 9, 5.

[11] Rodowick, 11.

[12] Qtd. in Yosefa Loshitzky, The Radical Faces of Godard and Bertolucci. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1995. 48.

[13] Rodowick, 5.

[14] The Fictional Christopher Nolan. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2012. 113.

[15] I refer in this essay to McGowan’s work on Christopher Nolan but I do not assign it as a reading for my students. Instructors may choose to assign McGowan’s chapter on Inception in lieu of the Rodowick reading or, if teaching a more advanced course (perhaps a graduate course or advanced undergraduate course on film theory), assign both.

[16] This observation will no doubt spark a discussion among students about whether or not we consider the act of inception a “success”—and, further, whether or not Cobb is still dreaming and, if so, whether or not we may consider this the film’s “success.”

[17] Ibid., 150.

[18] Ibid., 151.