Teaching Devdas and Mirch Masala: Indian Cinemas in the Global Cinema Classroom

Ani Maitra

One of my main challenges in “Global Cinema” has been to train my students to be sensitive to the complex relationship between the regional, national, and/or transnational social and political contexts shaping a film and those represented within the film. I also want them to be alert to the dangers of assuming a one-to-one correspondence between the film and the “real” culture of the nation that the film seemingly represents. While an awareness of the continuities and the discontinuities between the conditions of cultural production and the representation of culture is crucial to every national context/industry that my students encounter in class—from French counter-cinema to “extreme” South Korean cinema—in this piece, I will focus on my experiences and strategies of introducing students to contemporary Indian cinemas through two contrastingly reflexive representations of “Indianness”—Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas (2002) and Ketan Mehta’s Mirch Masala (1987). In what follows, I discuss how I teach a unit on Indian cinemas over a couple of weeks to students who have little or no familiarity with Indian film history and the linguistic-cultural diversity within India. I show how it has been useful to turn to Bhansali’s Devdas as the quintessential “Bollywood” text that constructs a mythical (colonial) India for its twenty-first-century global audience. Our discussion of the film focuses on the deliberate aesthetic choices it makes to produce a spectacular simulacral India for a transnational marketplace. I then introduce my students to Mirch Masala as an example of Parallel Indian (counter-) cinema that offers (with a very different kind of reflexivity) a far less spectacular and more auto-critical representation of (colonial and post-colonial) India. I also discuss why it has been productive to juxtapose these two post-Independence representations of colonial India that allow my students to delineate at least two competing cinematic legacies structuring representations of Indianness and Indian culture, and more broadly, two contrasting attitudes towards the self-referential logic of the spectacle. Finally, I demonstrate why it has been generative to compare the use of song-and-dance routines in the two films that approach the relationship between gender, social space, and national culture in diametrically opposed ways.

Introducing Bollywood’s “India”

In week five of “Global Cinema,” as we begin our unit on Indian cinemas and our week on Bollywood, I ask my students if they have ever seen “an Indian or a Bollywood” film. Their response is most often one of the following: they have seen a couple of films but cannot remember anything other than the colorful song-and-dance routines; they gingerly ask if Moulin Rouge! (dir. Baz Luhrmann, 2001) and Slumdog Millionaire (dir. Danny Boyle and Loveleen Tandan, 2008) count as “Bollywood”; they have not seen a Bollywood film but have a “general” sense of its heightened melodrama, its disregard for verisimilitude (“it’s not realistic”), elaborate dance routines, and its extraordinary length. I respond by saying that, rather than policing what is or isn’t Bollywood, it would be more productive to take their responses as illustrative of the development of a transnational idiom called Bollywood, of the politics of cultural translation that we can call “Bollywoodization” that many of us can identify even without having seen a Bollywood film. (At this point in the discussion, I say nothing about the conflation of “Indian” and “Bollywood” in my opening question.) As we watch a few minutes of the chartbusting song “Chamma Chamma” from the 1998 Rajkumar Santoshi film China Gate (that none of my students are usually familiar with) followed by its brief kitschy reproduction in Luhrmann’s rendition of early 20th-century French cabaret (that some in the class have already called “Bollywood-esque”), at least one student finds the racialized reappropriation of the song in Moulin Rouge! to be “parodic” and/or “objectionable.” We lean on this critique of Luhrmann’s recycling of “Chamma Chamma” to start unpacking the differences between the materiality and specificity of mainstream Hindi cinema—as an industry that is physically and historically grounded in Mumbai, India—and “Bollywood” as a repeatable, transportable, and translatable idiom/form that we “recognize” in Moulin Rouge!, Slumdog, or even “Bollywood dance groups” on North American campuses. Over the next two sessions, we examine the emergence and dominant traits of this local-global aesthetic by analyzing Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Devdas (2002) alongside readings by Andrew Willis, Tejaswini Ganti, and Jigna Desai.[1]

Students typically find these critics’ arguments about the transformation of the formulaic Hindi blockbuster into a more global Bollywood to be both accessible and intriguing. Through this scholarship, we begin to understand why—even as popular Hindi cinema had acquired certain specific characteristics by the 70s and 80s (such as the use of stock narratives, dance routines, star power, intertextuality etc.)—Indian cinema’s international recognition, as “Bollywood,” was a product of a very particular socio-political conjuncture in the 1990s. The economic liberalization of India, a larger diasporic viewership of Hindi films made possible by major changes in the Indian television industry, and, consequently, generous diasporic remittances produced by nostalgic nationalist investments in cinema from India together gave Hindi cinema an unprecedented makeover. This transformation therefore not only entailed bigger budgets, better technology, and significantly more lavish sets, but also idealized representations of “Indianness” and Indian (read Hindu) “traditions” to preserve the diasporic nostalgia that proved to be very lucrative, accounting for as much as 65% of a film’s total box office remittance.[2]

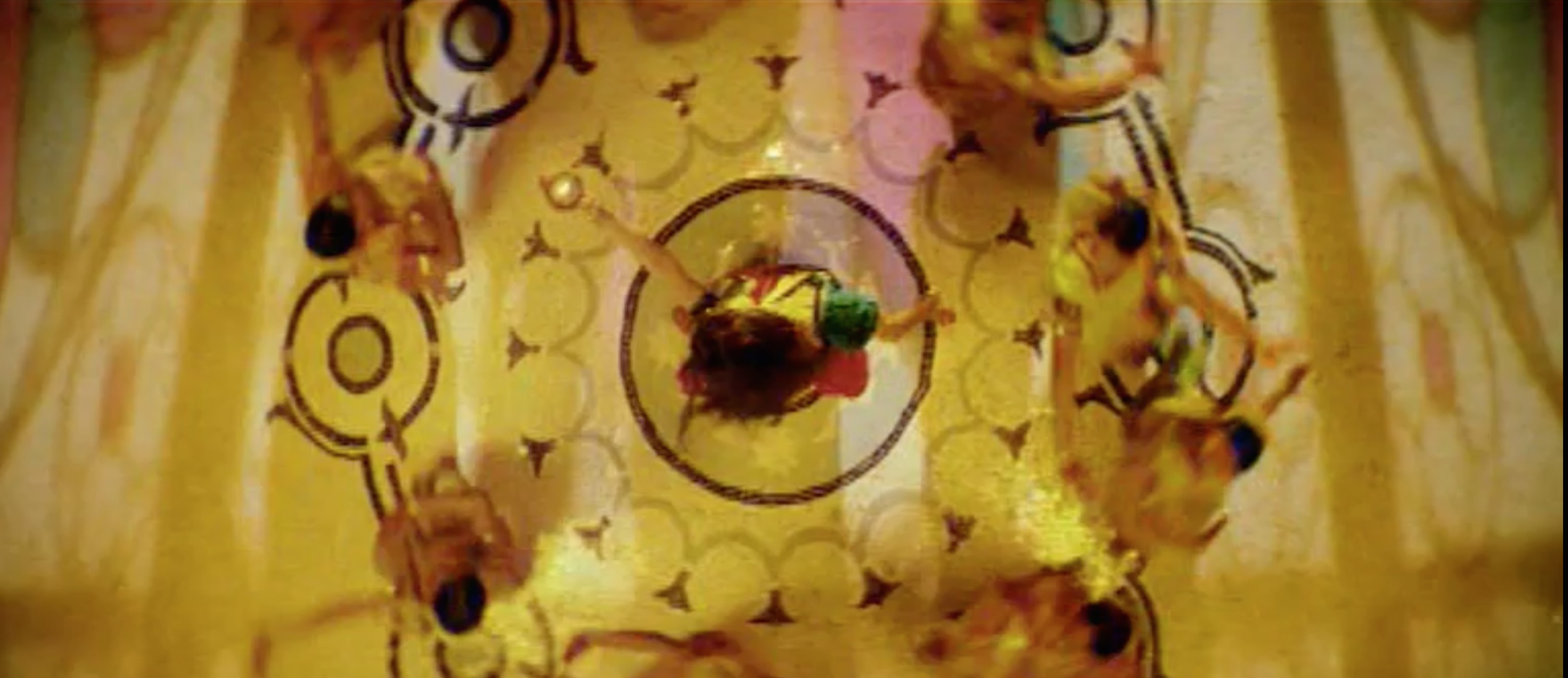

With a better understanding of the national and transnational forces responsible for the emergence of Bollywood, we are now ready to analyze Bhansali’s Devdas—a 2002 adaptation of a 1917 novel set in colonial Bengal—as one of the most extravagant “after” images of the makeover outlined above. We spend some time discussing the plot (a tragic tale of lovers separated by class difference) that irks many of my feminist and postfeminist students: “Why are the two leading ladies so obsessed with this blatantly arrogant and self-sabotaging (anti-)hero who mistreats them? Is the caste system in India (still) that rigid?” We work through some of these questions by discussing the literary origins of Devdas as a modern anti-hero and the evolution of the literary character into an enduring symbol of the contradictions of Indian modernity through cinematic adaptations (in several Indian languages) beginning in 1935. By the second class, I am able to steer the conversation toward thinking about the 2002 version as a post-liberalization Bollywood film, as a familiar Indian story or “content” that is given a very new “form” by Bhansali and his team. We examine how, from the very first establishing canted angle shot of a massive mansion representing colonial and aristocratic Bengal, Bhansali’s film is a kaleidoscopic fantasy called (colonial) “India.” We play close attention to the ways in which the film’s female stars Aishwarya Rai and Madhuri Dixit—in their elaborately choreographed and stunningly costumed dance sequences—visually elide all socio-economic differences between characters, hierarchies of caste and class that are, in fact, central to the narrative. In addition to examining this tension between the film’s style and content, we also note how the singing-and-dancing female stars directly solicit the audience’s gaze in a manner that is reminiscent of the reflexivity of the (European) “cinema of attractions” in the nineteenth century.[3] However, in this case, the gaze is also shaped by a twenty-first-century “ethnic” reflexivity, an awareness of what will sell as a glamorous “Indianness” in the transnational market place [figure 1].

Finally, we pause to reflect on Bhansali’s recurrent use of vertiginous high-angle and bird’s eye-view shots of the film’s female protagonist Paro (played by Rai), who is repeatedly “miniaturized” by the grandeur of the pro-filmic space depicting her father’s and husband’s mansions [figures 2 and 3]. I now encourage my students to extend Willis’s argument further, into Bhansali’s framing of these gendered domestic spaces. We discuss how and why the spatial isolation of women-as-spectacle in Devdas fetishizes not only female entrapment and isolation within colonial Bengali/Indian patriarchy but also contemporary Bollywood’s ritzy simulation of rural India for a global and diasporic audience.[4] This is a representation of female entrapment that is also meant to evoke “visual pleasure” through the expansive mise-en-scène, the costumes, and notably the construction of a certain dazzling “brand” India through Rai, the female star who, incidentally, was also the Indian contestant for and winner of the “Miss World” pageant in 1994.

Figure 3: Paro (played by Rai) trapped in the patriarchal household in Devdas (dir. Sanjay Leela Bhansali, 2002)

Both fascinated and perplexed by the sheen of Bollywood and its critical assessments, my students now raise questions that allow us to complicate further terms like “Indianness” and “Indian culture”: “If Bollywood films cannot be taken as ‘authentic’ representations of contemporary India, which films are more ‘honestly’ Indian?” Some students respond by asking if any film can/should take on that burden of representing an entire country. Others suggest that Bollywood’s India isn’t so much about “faking” as it is about being aspirational, about achieving a certain kind of global recognition for India. Still others take us back to an essay by Susan Hayward that we had encountered earlier in the semester: “Doesn’t Hayward argue for a progressive ‘national’ cinema that aesthetically interrogates the very concept of a (homogeneous) nation prompting viewers to reflect on differences within that ‘imagined community’ at any given moment? Don’t the song-and-dance routines and the overall visual extravaganza that is Devdas flatten these internal differences even as the plot ostensibly revolves around hierarchies of gender, class, and caste in colonial India?”[5]

The Intersectional and Introspective Gaze of Parallel Cinema

Using these questions as a segue, we move into the second half of our unit on Indian cinemas. I ask my students: What if we think about Indian cinemas historically and aesthetically in a more expanded frame, in terms of regional Indian cinemas that may or may not conform to the norms established by Hollywood or the Hindi blockbuster that became Bollywood? What kind of “national” cinemas do we run into then? We look at a linguistic map of India to get a sense of linguistically and culturally divided regions and the regional film industries, and finally turn our attention to a lesser-known genealogy of regional, art house or “Parallel” Indian cinemas. Through clips from Satyajit Ray’s Song of the Little Road (1955), Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome (1969) and, finally, a screening of Mehta’s Mirch Masala, we discover how, this alternative strand of cinema, albeit internally heterogeneous and not always averse to the “popular,” collectively prefers a certain kind of stylistic austerity and economy to the dominant mode of spectacle and excess: on-location shooting and lesser known actors to grandiose sets and big stars, and even avant-garde techniques that challenge the limits of the hermetically sealed world of classical cinema. We dwell on Parallel Indian Cinema as a complex and mutating phenomenon overdetermined by a number of (often contradictory) cultural, economic, and political factors—the eagerness of Indian filmmakers since the 1950s to break away from the dominant song-and-dance formula; funding supplied by the Indian government so that India produces not just “low grade” entertainment films but “high” art cinema that will garner global attention; and, simultaneously, the filmmakers’ desire to represent a more local (and not just a national/global fantasy called) India more attuned to the realities of the internally split postcolonial state.[6] By the end of this class session, we are therefore able to make a conceptual distinction between the history of Indian cinemas and that of the subset called Bollywood. A brief discussion of Ray’s career—beginning with the premiere of Song of the Little Road at the MoMA in New York—also makes clear the fact that regional Indian cinema has been simultaneously local and global well before the arrival of Bollywood.

In the next class meeting, we begin our discussion of Mirch Masala. If Bhansali’s Devdas is a tragic love story that unfolds through mesmerizing dance sequences in hyperreal patriarchal edifices that objectify and imprison women, Mehta’s film tells a powerful story of feminine resistance in India under British rule: Sonbai, a laborer in a spice factory in rural Gujarat, defiantly refuses the advances of a corrupt and predatory local tax collector (subedar) visiting the village with a gang of of marauding soldiers. Chased by the subedar’s henchmen, a desperate Sonbai seeks refuge in the factory whose doors are guarded by the ageing Muslim gatekeeper Abu Miyan. While most of the villagers—including the other women working in the factory—fear the subedar’s wrath and try to coax and taunt Sonbai into giving herself up, Abu Miyan stands firm in his resolve to protect her, barring even the factory owner and the village chief from entering inside. The guard’s insubordination ultimately costs him his life—the subedar shoots and kills Abu Miyan as soon as the soldiers tear down the factory door. However, in the symbolically charged final moments of the film following Abu Mian’s death, the women in the factory spontaneously rally around Sonbai and attack the subedar’s eyes with sacks full of powdered chilies from which the spices are made. The subedar falls on his knees screaming in pain as the chilies burn his eyes. In the final shot of the film, Sonbai breaks the “fourth wall” in a medium close-up, confronting us with her defiant gaze.

While comparing Bhansali’s and Mehta’s depictions of colonial India, we notice some key differences at the level of the narrative. First, while Devdas focuses on the private lives of the colonized, the larger political climate of colonialism remains peripheral to the love story between the protagonists. (Bhansali’s Devdas is an upper-caste Bengali educated in England but the film itself has little to say about the social impact of the British occupation of India.) Mirch Masala, however, offers a more complex view of colonization. Although the visiting subedar represents British presence, he is, significantly, an Indian subject, an indigenous comprador who is utterly indifferent to the plight of the illiterate and extremely poor farmers and factory workers. Second, even as the narrative underscores the urban/rural divide in India—the subedar enthralls the villagers with the wonders of the gramophone player—Mehta’s film also draws our attention to further hierarchies of gender and caste within the village. The village chief assaults and locks up his wife when she attempts to lead a women’s march protesting the men’s decision to hand over Sonbai to the subedar; simultaneously, the plot emphasizes the fact that Sonbai is treated as an expendable object by the villagers because she is not upper caste like the village chief or his wife. Importantly, these hierarchies are not represented as being simply “autochthonous” to India but as relationships indirectly abetted by the colonial system of exploitation and oppression (via the figure of the subedar) in the name of “governance.”

Next, our class turns to the aesthetics of the film, beginning with the obvious differences between the shimmering interiors of the mansions in Devdas and the earth tones of rudimentary huts and outdoor shots of a far more rustic countryside in Mirch Masala. Students also note how the color red, in particular, produces divergent associations in the two films. In Bhansali’s film, red is frequently used in the opulent decor, in costumes, as the decorative dye used by Paro on her hands and feet, and of course in the dramatic scene where Devdas hits Paro causing her forehead to bleed. Red, here, seems to connote romantic love, passion, and perhaps even a “deathly passion” foreshadowing the anti-hero’s death by tuberculosis. Cut to the opening credits of Mirch Masala, where long shots of rural women working the land are followed by a close-up of a deep red chili pepper against the green foliage on the ground [figure 4]. Henceforth, throughout the film, red recurs in the various settings and spheres within this agrarian community—on the headdresses of the men assembled in public spaces, on the clothing of the women in the factory, and most powerfully in long shots of massive heaps of chili peppers that visually diminish the plundering soldiers [figure 5], anticipating the women’s resistance in the final scene.

Figure 4: The opening credits foreground the centrality of the red crop in Mirch Masala (dir. Ketan Mehta, 1987)

Figure 5: The red crop “miniaturizes” the marauding soldiers in Mirch Masala (dir. Ketan Mehta, 1987)

Having established that Mehta’s visual emphasis lies not on a seductive “brand (Miss) India” but on the association between female agricultural labor and the products of that labor, we move towards a comparison between the spatial politics of Bhansali’s and Mehta’s films, particularly with regard to the song-and-dance scenes. Against the high-angle shots of the isolated and domesticated woman-as-Bollywood in Devdas, we examine the single song-and-dance scene in Mirch Masala. Significantly, this is a scene that is shot outdoors—the women gather in a circle in the village square to dance to a folk song, a sight that provokes the men’s (specially the subedar’s) quite visible erotic pleasure. However, a number of students are quick to point out that, compared to the carefully framed performances of the resplendently attired Rai and Dixit in Devdas, the dance in Mirch Masala is strikingly lackluster and appears to be filmed in a rather haphazard manner. The scene alternates somewhat erratically between high-angle shots including the dancers and their spectators, medium-shots of the men and the dancing women, close-ups of the lustful subedar presumably watching Sonbai, close-ups of the women’s feet, and, finally, out-of-focus extreme close-ups of the swirling red skirts of the dancers. Furthermore, while close-ups of the subedar call attention to his objectification of Sonbai, the camera refuses to align our gaze with his, offering us profiles of several women instead. Might this lackluster quality and lack of focus be, some students suggest, not just due to the low production value of the film but also a deliberate aesthetic choice underscoring the objectification of women under patriarchal systems without perpetuating the same?

This observation takes us deeper into the analysis of the scene and simultaneously allows us to turn to the assigned essay by Ranjani Mazumdar on gender in Indian Parallel Cinema.[7] I now ask my students to read the dance scene through Mazumdar’s main argument about the film, which is simply that, in Mirch Masala, Mehta rejects the gendered separation of the public and the private realms, repeatedly prompting spectators to see the women’s personal experiences of gender in colonial India in relation to their larger social experiences of class and caste. That is to say, gender in the film is not confined to the domestic space or to an essentialist notion of domesticated femininity (as suggested for instance, by Bhansali’s Devdas). Instead, Mehta’s film, Mazumdar argues, repeatedly locates patriarchal oppression “outside,” in the public realm, in the hierarchical social matrix, captured for instance, by the high-angle shots of the dancing women surrounded by a larger community [figure 7]. These high-angle shots, in a sense, represent an “intersectional gaze” that sees gender oppression articulated in and through larger and distinct forms of oppression represented by patriarchal and colonial agents like the village chief and the subedar. Needless to say, this discussion is most fruitful when we visually compare the intersectional gaze in Mirch Masala with the now-familiar high-angle shot in Devdas where domestic grandeur at once emphasizes and romanticizes patriarchal violence inflicted on the socially isolated woman-as-spectacle [figure 6].

As we near the end of our comparative discussion of Bollywood and Parallel Indian Cinemas, I reintroduce the concept of “reflexivity.” How should we distinguish between the modes of reflexivity or self-awareness demonstrated by Devdas and Mirch Masala? Formal choices that point towards Bollywood’s self-awareness in Bhansali’s film, we recall, are determined, in part, by the desire to manufacture a slick and visually homogeneous national image of India for global consumption. In contrast, Mehta’s film demonstrates a visual reflexivity that looks inwards, at fissures within the national and rural body politic. This skepticism makes sense, given that Mehta’s film was produced in post-Emergency India soon after the tenure of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, a period marked by ruthless centralization, censorship, and ethnic and religious conflicts in the country.[8] If Bhansali’s lustrous representation of colonial India can be called an “allegory” of Bollywood’s technical prowess and its global ambitions in the twenty-first century, Mehta’s colonial India is literally and metaphorically a darker but more uncompromisingly feminist allegory of the power-hungry and repressive gaze of the post-colonial state in the 1980s. It is this repressive patriarchal gaze of the state that the women assault symbolically in the final scene of the film. Many of my students are ambivalent towards the ambiguous ending: “What do the women achieve by temporarily blinding the subedar with the chili peppers? Why does the film end so abruptly without telling us what finally happens to Sonbai?” Two Godard fans, however, read the ending differently: “Why can’t we think of the final scene and the last shot [figure 8] as a moment of ‘aperture’ and ‘foregrounding,’ especially since the final shot is of Sonbai confronting us, the (urban, privileged, cosmopolitan) spectators of Mehta’s film? Isn’t this the most powerful moment in the film in which the actor playing Sonbai ‘comes out’ of the fictional text to confront the audience with the predicament of the gendered subaltern? Can the women’s resistance in this context be anything but symbolic without becoming utopian?”[9] Not everyone is comfortable with this uncertainty produced by the text. But in closing, I tell my students how eerily relevant I find Mirch Masala’s unsettling critique of the Indian state on a week when twelve Indian filmmakers are returning their National Awards (the highest award given by the state) to protest religious and caste-driven violence under the current Hindu right-wing Indian government.[10]

Figure 8: Sonbai (played by Smita Patil) confronts her audience in Mirch Masala (dir. Ketan Mehta, 1987)

The author wishes to thank Colgate University students who took “Global Cinema” with him in the Spring and Fall of 2015. This piece would not have been possible without their incisive questions, astute comments, and spirited participation.

Ani Maitra is Assistant Professor of Global Film and Media in the Film and Media Studies Program at Colgate University. His teaching and research interests span the fields of post-colonial and diaspora media cultures and gender and sexuality studies. His essays have appeared in edited volumes and journals like Camera Obscura, Continuum, and Jindal Global Law Review. He is currently working on a book project on the aesthetics and politics of “intermedial narcissism” in diasporic film and literature.

Notes

[1] Andrew Willis, “Locating Bollywood: Notes on the Hindi blockbuster, 1975 to present,” in Movie Blockbusters, ed. Julian Stringer (New York: Routledge, 2003), 255-268.

Tejaswini Ganti, Bollywood: A Guidebook to Popular Hindi Cinema (London and New York: Routledge, 2004).

Jigna Desai, Beyond Bollywood: The Cultural Politics of South Asian Diasporic Film (London and New York: Routledge, 2004).

[2] See Willis, 255.

[3] We read Thomas Gunning’s essay on “cinema of attractions” early in the semester alongside his essay on global cinema. See Thomas Gunning, “The Cinema of Attractions: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde,” in Early Cinema: Space, Frame, Narrative, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Adam Barker (London: British Film Institute, 1990), 56-62. See also Thomas Gunning, “Early cinema as global cinema: the encyclopedic ambition,” in Early Cinema and the “National,” ed. Richard Abel, Giorgio Bertellini, and Rob King (London: John Libbey, 2008), 11-16.

[4] Students also encounter an excerpt from Laura Mulvey’s essay on the “male gaze” early in the semester and are familiar with the idea of the “woman-as-spectacle” in classical Hollywood and, more generally, popular narrative cinema. See Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology: A Film Theory Reader, ed. Philip Rosen, (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986), 200-204.

[5] Susan Hayward, “Framing National Cinemas,” in Cinema and Nation, ed. Mette Hjort and Scott Mackenzie (London and New York: Routledge, 2000), 88-102.

[6] Excerpts from Ray’s Our Films Their Films can be useful for this discussion. See Satyajit Ray, Our Films Their Films (Bombay: Orient Longman, 1976).

[7] Ranjani Mazumdar, “Dialectic of Public and Private: Representation of Women in Bhoomika and Mirch Masala,” Economic and Political Weekly (1991): WS81-WS84.

[8] I usually give my students a handout outlining some key historical events and periods like the Indian Independence, the Partition of India, the Nehruvian years, the Emergency, and Operation Blue Star.

[9] Students, at this point, are also familiar with the concepts of “aperture” and “foregrounding” through Peter Wollen’s essay on Godard. Wollen’s reading of Godard also resonates with Mazumdar’s reading of Mehta’s formal reflexivity. See Peter Wollen, “Godard and Counter-Cinema: Vent d’est (1972),” in The European Cinema Reader, ed. Catherine Fowler (London: Routledge, 2002), 74-82.

[10] Atikh Rashid and Dipti Nagpaul, “FTII row:12 filmmakers return national awards to join against national ‘intolerance’,” Indian Express October 29, 2015, accessed November 15 2015, http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/dibakar-banerjee-nine-other-filmmakers-return-national-award-to-protest-rising-intolerance/.