Teaching Born in Flames

Virginia Bonner

Figure 1: “Black women, be ready. White women, get ready. Red women, stay ready.”

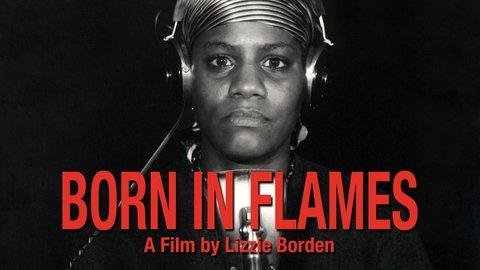

Born in Flames (Lizzie Borden, 1983)

“It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths. For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.”

—Audre Lorde[1]

During her 1983 interview with Lizzie Borden, just after the New York premiere of Born in Flames, Anne Friedberg describes “a certain discomfort” that the film demands of its audience. Borden counters that such discomfort lies in assuming a solely white middle-class audience, and that tellingly, women of color and other marginalized groups who saw the film did not express discomfort. But Borden emphasizes how she worked to diversify the typically white audience when Born in Flames screened at Film Forum; she actively targeted mailing lists for Black women, Black men, and the LGBTQ community, some of whom had never heard of Film Forum or even went to see films.[2]

About fifteen years later, I experienced Born in Flames myself. I was in graduate school in the late 1990s, pursuing a double major in Women’s Studies and Film Studies. I was passionately reading theory—Marxist, Film, Race, Feminist—and eager for films that challenged my own positionality as a middle-class white woman. So it is perhaps not surprising that Borden’s radically fierce film struck a chord with me (not coincidentally, Borden had been reading these same texts when she made it). Yet Born in Flames embodied so much more than these theories alone: its raw filmic style, its defiant punk music, its smart sci-fi genre bending, its trenchant political bite, its militant feminism, its multiracial and cross-class collaboration. I had never seen anything like it. Born in Flames productively destabilized many of my preconceptions during that heady time that characterizes so much of graduate study—and it continues to challenge my teaching today. Over the many years that I have taught this film, I have learned the hard way that Borden’s targeted diversification of her audience fundamentally affects the pedagogical promise of the film.

Born in Flames is set in a near future U.S. (though it pointedly looks very present), a decade after a Socialist Democratic Cultural Revolution has purportedly created equality between the sexes. Of course, it hasn’t created equality in practice; despite official messages proffered by the media, women are still discriminated against in the workplace, sexually attacked on the street, and undervalued in the home. Four groups of women separately mount challenges to these structural inequalities; the Women’s Army activists, academic journalists, and two underground radio stations are variously comprised of poor women, non-white women, lesbians, and white middle-class women. When these disparate groups band together, they successfully take over the ultimate power source: the media. Importantly, as real-life activist Flo Kennedy voices in the film, it is precisely the women’s valuing of their different strengths that proves so crucial to their fight; or to quote Audre Lorde, their differences must “spark like a dialectic” to effect change and revolution.[3]

To tell this story, Borden necessarily defies traditional filmmaking rules, as did other low-budget feminist films of the 1970s-80s, by blending documentary and fiction, casting nonprofessional actors, and eschewing Hollywood gloss. But Born in Flames goes further—to the point of having been called “a mess” by more than one critic and countless students. By strategic design, the film offers no seamless narrative, no central protagonist, and little psychological character development. Natural sound sometimes misses the mostly improvised dialogue or awkwardly postdubs it, and its loud punk soundtrack frequently overpowers the dialogue and ambient sound entirely. Handheld camerawork and jump cuts transition jarringly, often with little continuity. In fact, Borden had to film scenes months and even years apart, yet she refuses to match previous shots. Of course, Borden’s unprecedented story couldn’t have been told any other way; its raw style exudes its political bite.

Such a film—a rare embodiment of theory, art, activism, and pleasure—resonated so strongly with my cohort of feminist film graduate students that I knew it would prove a stunning and powerful text for my undergraduate students. I was eager to share Born in Flames with a new generation.

Unfortunately, the first time I taught Born in Flames, it was a disaster. I had assigned it for a section of Introduction to Women’s Studies in Fall 1999—at, I should note, a private university that serves predominantly white, wealthy undergraduates. By midterm, we had studied theories of gender, race, class, and sexuality via writings by Simone de Beauvoir, Patricia Hill Collins, Audre Lorde, and Adrienne Rich, among others, and via provocative films like Sally Potter’s Orlando (1992), Marlon Riggs’ Color Adjustment (1991), and Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991). I was confident that my students would now have enough theoretical and filmic preparation to respond to Born in Flames with enthusiasm to match my own, if not more, given their youth and passion.

But the students’ response proved lackluster: they found the acting poor, the graininess unpolished, the narrative disorganized, the science fiction too realistic, the punk music too old-fashioned and grating. They laughed aloud as the women on bicycles stopped the rape on the street. They yawned at the activist monologues to camera. They shrugged apathetically at the women’s collaborative sabotage of mainstream media. And overwhelmingly, the young white women at this private university were uncomfortable identifying with the film’s diverse women—white or Black.

Born in Flames is indeed critical of its white women, whom it depicts as too analytical and cerebral, too disengaged—until they stop promoting the Party’s illusory message of unity (the Master’s House, Lorde would say) and join the cause that poor women, Black women, and lesbians are already fighting. During class, I showed several clips to chart these white women’s path from intellectual myopia to consciousness and finally to action alongside the women of color and lesbians—one of the film’s truly sci-fi hypotheticals, since it exposes the actual exclusions instigated by Second Wave white feminists in the 1970s-80s. Certainly, the film’s accurate criticism of white women undergirds part of the “discomfort” that Freidberg and other white viewers, including these students, reported.

But shockingly, these white Intro students didn’t even remember that there were Black women in the film with whom they could identify instead. Even as we viewed multiple clips illustrating the film’s diversity of women, I had to remind students about major Black characters: “Okay, but how did you respond to Honey’s character?” and “What about Adelaide’s activism? And Zella, the real-life activist Florynce Kennedy, who mentors Adelaide?” Students resisted identifying with any of these women of color. At the time, I (mis-)diagnosed a generational disconnect, and I sadly removed the film from this Intro course.

Figure 3

Honey (figure 3), Zella, and Adelaide (figure 4): White students resisted identifying with any of these women of color. Born in Flames (Lizzie Borden, 1983)

I taught Born in Flames again in an upper-division Women and Film course in the mid 2000s, soon after I began my teaching position at my current institution. In those years, this public university was majority white and predominantly middle class; these students were not as wealthy as the undergraduates I had taught while I was a graduate student, but they were still comfortably class and race privileged. Despite this shift in class, any diverse perspectives afforded by our classroom discussion remained limited at best, and these students responded as before. They could not connect with the film’s low-budget aesthetics, multiple protagonists of color, or political message. So again, I removed the film from the course.

It wasn’t until years later that I fully processed what Borden had pointed out to Friedberg upon the film’s release: the problem was far more complexly related to audience demographics and pedagogy. It wasn’t the film, but the lack of racial, sexual, and class diversity in those classrooms that impeded students’ awareness of their own positionality and that of others. And ironically, I had approached Born in Flames like its own diegetic white women who most resemble me: too theoretically and too blind to the pitfalls of our homogenous classroom. My role as a young white female instructor, enthralled with theory but still inexpert at facilitating diverse experiential discussions, likely exacerbated the impasse.

But now, over a decade later, my teaching of Born in Flames and many other films is richer because the student demographics at this same university are considerably more inclusive. Our student body is majority female, majority Black, and predominantly working class, with a significant international population and a high number of first generation students (first to attend college in their family). Students in general are more aware of the politics of identity, more versed in film language, and more wary of media control. And my teaching methodologies have evolved with the diversification of our students: from the films I teach and research, to the ways I lecture and lead discussions, to the diversity and inclusive pedagogy workshops I attend. To boot, Born in Flames has enjoyed renewed interest of late, since it is now more readily available streaming, and Anthology Film Archives premiered its restored 35mm print in February 2016 (on my birthday, even).

So in Fall 2016, I felt compelled to teach Born in Flames again in Women and Film. The results were remarkable—as if it were an entirely different film. And truly, it was a different film, because the students’ diversity sparked a wider range of life experiences and identificatory positions that I could now facilitate in our classroom discussion. White and Black students animatedly described how and why the film moved them: its themes of rape culture and economic exploitation are still so current; it exposes the ways media control us; and especially, it empowers women of color and lesbians. Born in Flames became a touchstone throughout our course together; several Black male students even ranked it their favorite film that term and shared it with friends recreationally.

Part of this success also results from some strategic changes I made to the film’s timing in this Women and Film course, and to its accompanying readings and clips. I am now careful to slate Born in Flames after Section 1 on classical Feminist Film Theory, and specifically in the middle of Section 2 on Feminist Counter Cinema. This positions the film just after we study Michelle Citron’s Daughter Rite (1978), Su Friedrich’s Hide and Seek (1996), and Annette Kuhn’s “Textual Politics” article (1990),[4] all of which function to introduce Counter Cinema’s low-budget aesthetic, female voice, and documentary influence. This middle location also places Born in Flames just before more experimental films, like Trinh T. Minh-ha’s Reassemblage (1982), Tracey Moffatt’s Nice Coloured Girls (1987), and Marzieh Meshkini’s The Day I Became a Woman (2000). So situated, Born in Flames feels comparatively narrative and accessible, and it transitions well to these films by and about international women of color.

To focus more on the film, I also now reduce accompanying readings to excerpts from four brief texts (about thirteen pages total), two authored contemporaneously with Borden’s film and two recent interviews:

- Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” (1979).[5] Students eagerly debate the possibilities and limitations of this short essay’s central metaphor (see epigraph), and they readily connect it to the diverse women’s interactions in Born in Flames. Via Lorde, students understand why the film’s protagonists demand a multiplicity of races, classes, and sexualities, and why their struggle demands not divisive exclusions but interdependence among diverse women to achieve any measure of liberation.

- Hélène Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa” (1975).[6] Students find Cixous’ écriture féminine less accessible—but by design. Both Cixous and Borden re-envision narrative, so neither writes a seamless masculinist narrative for their feminist goals. During class, I draw on the board Freytag’s linear plot structure modeled on masculine pleasure, and then contrast it with a feminine model that peaks multiply… and spirals… with tendrils—it looks like a surreal tentacled centipede. Students find this hilarious, which breaks the tension around Cixous’ challenging piece, and it really cements her point for them. They now understand why Born in Flames must be edited as a collage/mosaic—how its nonlinear multiplicity defies a racist-heterosexist-patriarchy through its form. It seeks to “take pleasure in jumbling the order of space, in disorienting it” and “to smash everything, to shatter the framework of institutions, blow up the law, to break up the ‘truth’ with laughter.”[7] Clips from Sally Potter’s Thriller (1979) and Marlene Gorris’ A Question of Silence (1982) also help students hear Cixous’ empowering, orgasmic “rhythm that laughs you”[8] in Born in Flames’ dialogue. Improvised by its non-actors, these are the voices of diverse, real women that a formal script written by Borden and spoken by professional actors would have denied.

- Kathleen Hanna, Riot Grrrl punk music icon and feminist activist, explains in a 2013 interview[9] how Born in Flames inspired her music, but also how white feminists exclude women of color and lesbians, making those racist-heterosexist errors described by Lorde. She calls Born in Flames “a potential blueprint for feminist change” because it dares to represent “different points of view in one movie, showing that different points of view could exist at the same time.” During class, I also show a few clips from The Punk Singer (Sini Anderson 2013), the recent documentary about Hanna; these frame Born in Flames’ use of feminist punk music, which enjoys equal footing with the images and monologues. Borden thought younger audiences could “get the meaning faster” through the driving beat.[10]

- Students always appreciate hearing from the film’s director. In a 2016 interview Borden richly discusses her influences, her filmmaking process, the 1980s era and downtown New York art scene, today’s audiences for Born in Flames, and her continued goals for the film.[11]

Borden designed Born in Flames to express a plurality of experience—“different voices of diverse women,” as she puts it[12]—and recognized the value of an inclusive audience. It’s a blueprint for our classrooms too.

Virginia Bonner is Professor of Film Studies and Coordinator of the Film Minor at Clayton State University. Her research focuses on documentary, independent, avant-garde, and feminist cinemas, and her publications on these films are included in There She Goes: Feminist Filmmaking & Beyond, Senses of Cinema, Scope, In Media Res, and Documenting the Documentary: Close Readings of Documentary Film and Video, 2nd edition.

Notes

[1] Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” (1979), in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. (Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 1984), 112.

[2] “An Interview with Filmmaker Lizzie Borden,” Interview by Anne Friedberg, Women and Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 1:2 (1984): 38, 43.

[3] Lorde, 111.

[4] Annette Kuhn, “Textual Politics,” in Issues in Feminist Film Criticism, ed. Patricia Erens (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 1990), 250-267.

[5] Lorde, 1979.

[6] Hélène Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa” (1975), Signs: Journal of Women’s Culture and Society, 1, no. 4 (1976): 875-893.

[7] Ibid., 887, 888.

[8] Ibid., 882.

[9] “Kathleen Hanna on the Film That’s Inspired Her for Decades,” Interview by Sam Adams, The Dissolve (December 2013) https://thedissolve.com/features/mad-love/298-kathleen-hanna-on-the-film-thats-inspired-her-for-/

[10] Borden interview with Anne Friedberg, Women and Performance, 43.

[11] “Stay Ready: Lizzie Borden on the Post-Revolutionary Future of Born in Flames,” Interview by Alison Kozberg, Walker Art Center Magazine Crosscuts (April 2016) https://walkerart.org/magazine/interview-lizzie-borden-born-in-flames

[12] Borden interview, “Stay Ready,” 2016.