Wiping the Dust from Our Eyes: (Re)cycling Iconic Images from American History’s Most Devastating Economic Depression

Lauren Newton Glenn

Fig. 1. Dorothea Lange. Woman of the High Plains, Texas Panhandle. (1938). Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection.

While the East Coast still reels from the devastating effects of Hurricane Sandy, documentary filmmaker Ken Burns hopes to remind American viewers of the wisdom gained from survivors of a different ecological disaster. His newest film, The Dust Bowl, about the drought and subsequent dust storms of the 1930s, aired on PBS November 16th and 17th.[1] Burns’s visual style recycles some of the most iconic photographic images of the greatest manmade disaster, cleverly juxtaposing the most recognizable photographs with unseen newsreel footage and survivor interviews. Just following the fifty-seventh presidential election, the film premiers at a time when citizens remain concerned about an imminent economic depression, “green living” is politically correct, and issues concerning the economy and our ecosystem seem intertwined. Fittingly, the power of Burns’s most recent documentary lies in its own recycled images, recalled from a not-too-distant past.

The migration of the “suitcase farmers” following the Dust Bowl of the 1930s remains one of America’s most photographically recognizable time periods. Ken Burns says he felt an urgency to make the documentary since so few eyewitness survivors of the decade-long disaster remain.[2] Yet, despite the decreasing number of survivors, images and descriptions of this time period continue to circulate through our culture, keeping the history alive. The images of photographer Dorothea Lange, novelist John Steinbeck, and filmmaker John Ford exist as a primary “way-in” to understanding this important era in American history. The popularity of these images speaks for itself. The bestselling novel of 1939 and 1940, Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath continues to sell about one hundred thousand copies annually.[3] Similarly, seven decades after her photographs first appeared, many of Dorothea Lange’s images continue to impact contemporary viewers via art textbooks, literature, digital reproductions, and even as a U.S. postal stamp. In the 1930s, following their original publication in the Resettlement Administration reports, later known as the Farm Security Administration (FSA), Lange’s photographs influenced not only John Steinbeck, but also the stylistics of cinematographer Gregg Toland and director John Ford, who collaborated on the making of the filmed version of The Grapes of Wrath (1940).[4] Each of these important texts continues to be read and interpreted by viewers in the twenty-first century, their images working together to create a public memory of the migrant experience and the destruction of America’s great plains.

Just like John Ford before him, Burns based many of his moving images on Dorothea Lange’s iconic photographs, mimicking the visual composition literally and effectively making recognizable images “come to life.” This technique adds to the perception of reality, thus reinforcing spectator trust in the realism behind the screen’s image. Forty years ago, Peter Wollen emphasized the importance of the iconic pictorial sign. Borrowing from Charles Peirce’s triadic model of the sign and basing his theories on early childhood image recognition, Wollen argued that iconic and indexical aspects in cinema are more powerful than the symbolic.[5] More recently, in 2007, rhetoricians Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites contributed a significant study on American political iconic images in No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. They define iconic images as “images appearing in print, electronic, or digital media that are widely recognized and remembered, are understood to be representations of historically significant events, activate strong emotional identification or response, and are reproduced across a range of media, genres, or topics.”[6] Essential to their argument is that through reproduction and mechanical resituating, iconic photographs do not and cannot encompass an unchanging meaning. Instead, images change according to the frequency with which they are reproduced, the different contexts within which they are placed, and the means by which they are altered. The frequency of reproduction insures that iconic images remain recognizable despite minor changes to their context, function, or content. Ken Burns’s color cinematography reproduces the many iconic photographs of the FSA photographers so closely that he makes the familiar images come to life in new ways.

W.J.T. Mitchell’s most recent work further develops the idea of living, arbitrarily changing images. In his most emphatic and controversial argument, he compares the image to a biological species, claiming that it is alive, that it changes and evolves almost independently of its human creators and interpreters. He explains, “Images are not just passive entities that coexist with their human hosts, any more than the microorganisms that dwell in our intestines. They change the way we think and see and dream. They refunction our memories and imaginations, bringing new criteria and new desires into the world.”[7] Once a new image has been encountered, it affects other images that have been stored in memory, often changing perceptions and understanding. But, although Mitchell wants us to conceive of the image as alive, he also argues that, more times than not, it cannot die. Once images have been released to interpretative communities, it becomes impossible to recall those images since they exist independently within memory. Iconic images, in particular, cannot be retracted since they are so widely viewed. Images that have been repeatedly viewed and reconfigured survive beyond the control of their creators. They are used in contexts that vary widely from the ones in which they were originally created. These popular images change and grow, taking on new meanings when new artists modify them to speak to different audiences.

In the same way that Ferdinand de Saussure separates language from speaking,[8] Mitchell separates the image from the picture, demonstrating how the image exists independently from the original work of art as a floating entity: “You can hang a picture, but you cannot hang an image. The image seems to float without any visible means of support, a phantasmatic, virtual, or spectral appearance. It is what can be lifted off the picture, transferred to another medium, translated into a verbal ekphrasis, or protected by copyright law.”[9] The image is what lives on when the medium no longer exists. While one can destroy photographs, film, and novels, images continue to float freely from these mediums in our imaginations, perceptions, recreations, and collective consciousness once they have been received and interpreted. Therefore, following the publication of Lange’s photographs—once her images are stored in human memory—they no longer belong solely to the paper on which they were developed but rather to the individual or collective memories of the viewer(s). Likewise, Steinbeck’s descriptive images can exist independently from the bound pages of his novel, and the film’s moving images are separate from the flat screen on which they were originally projected, becoming disembodied from their original mediums. If these images exist independently from the mediums in which they were created, it is possible that they mingle and mix with similar images in the public’s perception, forming what I refer to as a “gestalt” of images, a term I borrow from Mitchell. To Mitchell, images can denote (among other things) an “overall formal gestalt.”[10]

While he mentions this term in passing, I would like to expound on it here. Although images can exist separately from one another (i.e., containing signification completely independent of meanings conferred by other media), in some instances the images from different types of media converge in memory, overlapping in meaning. Gestalt, then, makes up the structure or pattern of diverse phenomena so integrated that the construction constitutes a functional unit with properties that cannot be separated from the summation of its parts. In other words, once the images of Lange, Steinbeck, and Ford/Toland are released to the public for interpretation, the similarities between the images mesh or converge to create a new understanding about a topic or time period. Often the images that make up this understanding cannot be separated from one another. The resulting gestalt may be formed in individual memory as well as in public memory.

One example of how a gestalt is formed in memory can be demonstrated by the way Lange’s photographs frequently become linked to Steinbeck’s novel and Steinbeck’s novel linked to the visual images in Ford’s film. Those familiar with these images often do not read the novel without visualizing Ford’s characters, see Lange’s photographs without connecting them to Steinbeck’s Joad family, or see Ford’s filmic images without thinking of Lange, and so on. I agree with John Bodnar that “public memory” can be defined as “a body of beliefs and ideas about the past that help a public or society understand its past, present, and by implication, its future.”[11] Public memory can consist of theoretical concepts, shared images and understandings, as well as common values. In examining the impact of public memory, Laura Mulvey links the psychoanalysis of dreams to image association: “As well as the unconscious associative links in a dream’s latent material, in daydreams and reveries, the mind travels across unexpected, apparently arbitrary chains of association that may or may not be ultimately comprehensible when recalled to the conscious mind.”[12] Mulvey contends that the mind’s categorization of images may be similar to the recollection of daydreams. Previously viewed images return to the consciousness when triggered by similar or related images, even if they are not understood as related by the conscious mind. For example, Steinbeck’s written images can trigger memories of Lange’s photographs and Lange’s images can trigger memories of the Ford/Toland images in the film. For the public familiar with these related images, memory associates them with one another.

So, what makes the still images of Lange, the narrative images of Steinbeck, and the moving images of Ford/Toland so similar that they often respond to memory triggers as related or even interconnected in meaning? Despite the fact that the images of these artists resulted from differing ideologies and approaches, the images remain connected because viewers, teachers, and students continually group them together. In addition, there exist many visual and formal similarities among these four artists’ images. For my purpose here, I will focus on two characteristics that can also be found in Ken Burns’s The Dust Bowl: character portraiture and positioning of gaze.

Portrait of Character

Lange’s ideology of creating “realistic” documents as well as her awareness of the disdain for photography in certain artistic and academic communities would impact her approach to photography and the resulting portrayal of the migrant situation. As one of the most influential photographers during the Great Depression, Lange began her career as a portrait photographer, moving to San Francisco to open a portrait studio in 1918. However, as Lange watched unemployed workers lining up for federal relief under her studio window, she began to question the importance of her work as a photographer. She eventually moved her camera from her studio to the streets in order to photograph San Francisco’s most dispossessed citizens. She eventually took a job documenting the effects of the Great Depression for the Resettlement Administration, a program under President Roosevelt’s New Deal Administration. Her approach to documentary photography brought about a distinctive change in style from the approach she used in her studio. As she later reflected:

In those days, I used to try to talk people into having their pictures taken in their old simple clothes. I thought that if they did, the images would be timeless and undated. Now, I feel I was mistaken, and think that to have any real significance, most photographs have got to be dated. Also, I worked a lot closer to the subject then than I do now. Everything is shut out of many [early] prints but the head – there’s no background, no sense of time or place.[13]

Portrait photography creates the subject as one would like to appear–as a desirable and “timeless” image. Documentary photography, on the other hand, seeks to expose “reality,” make connections, and reveal time and place. In her most influential photographs, Lange combined her eye for portrait photography with her dedication to documenting real people. Perhaps her most famous photograph is “Migrant Mother.” In this image, Lange captures a portrait of one migrant woman while also framing her with the items that make her “real:” her children, the dilapidated tent in the background, and the tent pole in the foreground. Lange, however, instructed the children to turn their faces away from the camera, she asked the mother to move her hand to her face, and she later cropped the woman’s thumb (which was gripping the tent pole) from the negative. In so doing, Lange diverges from the documentary ideals of capturing unmediated reality to create a work of photographic art. The resulting photograph demonstrates how one image can exist as an archetypal representation of an entire group of people, or in this case, an entire era of migration.

Fig. 3. Dorothea Lange. Migrant Mother. (1936). Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection, [reproduction #LC-USZ62-95653-C].

The man’s clothes were new–all of them, cheap and new. His gray cap was so new that the visor was still stiff and the button still on, not shapeless and bulged as it would be when it had served for a while all the various purposes of a cap—carrying sac, towel, handkerchief. His suit was of cheap gray hardcloth and so new that there were creases in the trousers. His blue chambray shirt was stiff and smooth with filler. The coat was too big, the trousers too short, for he was a tall man. The coat shoulder peaks hung down on his arms, and even then the sleeves were too short and the front of the coat flapped loosely over his stomach. He wore a pair of new tan shoes of the kind called “army last,” hobnailed and with half-circles like horseshoes to protect the edges of the heels from wear. This man sat on the running board….[14]

The “photographic” image allows the reader to gaze at the character as he is introduced, as if the reader is looking at a photograph and is able to examine all the details of Tom Joad’s clothing in a frozen moment of time. If Steinbeck, instead, introduced the character in a moving sequence, the reader would not have the same opportunity to recognize all the intricate details as he or she would when examining a fixed photograph. Another example is his portrait of Jim Casey:

It was a long head, bony, tight of skin, and set on a neck as stringy and muscular as a celery stalk. His eyeballs were heavy and protruding; the lids stretched to cover them, and the lids were raw and red. His cheeks were brown and shiny and hairless and his mouth full—humorous or sensual. The nose, beaked and hard, stretched the skin so tightly that the bridge showed white. There was no perspiration on the face, not even on the tall pale forehead, lined with delicate blue veins at the temples. Fully half of the face was above the eyes. His stiff gray hair was missed back from his brow as though he had combed it back with his fingers. For clothes, he wore overalls and a blue shirt. A denim coat with brass buttons and a spotted brown hat creased like a pork pie lay on the ground beside him. Canvas sneakers, gray with dust, lay nearby where they had fallen when they were kicked off.[15]

With these two protagonists, Steinbeck pauses his narrative flow to allow the reader’s imagination to take in the details of their features. No movement is noted; instead, the characters are frozen in photographic likeness. Steinbeck’s style also emphasizes the textures within the image, just as Lange draws the viewer’s gaze to the gritty surface textures in her photographs. In “Migrant Mother,” the surface textures are highlighted by Lange’s use of sharp focus. The dirty clothing and dust-covered hair are illuminated, not hidden. Steinbeck describes the textures of Tom’s clothing and the musculature/texture of Casey’s face and neck in detail just as Lange highlights textures with focus and lighting. By emphasizing textures and small details, Steinbeck presents these characters as portraitures. Through his imagery, he is giving the reader an up-close and personal view of these characters.

Fig. 4. John Ford and Gregg Toland. The Grapes of Wrath Movie Still. Twentieth Century – Fox Film Corp. (1940)

Similarly, in the film, director John Ford and cinematographer Gregg Toland pause the momentum of movement to create photographic likeness. Dialogue scenes of importance are emphasized in shots in which the speaking characters are standing still. Vivian Sobchack criticizes, “The relative lack of physical movement by the characters when someone has something important to say (a ‘speech’ such as Casey’s on not being a preacher, or Muley’s on being ‘touched,’ or Ma’s on Tom’s not becoming mean) makes the dialogue denser than it might otherwise be if lightened by some random motion.”[16] Indeed, many important moments in the film are presented in stillness. Sobchack, however, misses the film’s connection to photography. Just as Steinbeck stills his narrative flow, Ford halts the film movement for important moments of character dialogue, often utilizing mirrors or door frames to frame characters frozen in a portraiture stance. At these moments, the posture of the characters with slightly slumped shoulders, the awkward hand positioning, and the eyes averting the camera reflect the style of Lange’s portraits. In these scenes, the characters are positioned as portraits, and the viewer is allowed to examine them with relatively little movement hampering the gaze.

One scene in particular clearly emphasizes the influence of portrait photography. In the novel, Ma Joad takes a moment alone to sift through her small belongings:

She reached behind one of the boxes that had served as chairs and brought out a stationery box, old and soiled and cracked at the corners. She sat down and opened the box. Inside were letters, clippings, photographs, a pair of earrings, a little gold signer ring, and a watch chain braided of hair and tipped with gold swivels. […] For a long time she held the box, looking over it, and her fingers disturbed the letters and then lined them up again. She bit her lower lip, thinking, remembering.[17]

Fig. 5. John Ford and Gregg Toland. The Grapes of Wrath Movie Still. Twentieth Century – Fox Film Corp. (1940)

Ford and Toland translate this scene beautifully. In the film, Ma is sitting in front of a stove fire, sifting through the souvenirs of her life. Here, Toland utilizes his famous “available lighting” technique with the fire, and the scene is almost completely dark. Shadows flicker, dancing with the flames throughout the scene. As Ma examines several small trinkets, the camera looks down on each of them so the viewer is seeing through Ma’s eyes. She holds up a postcard from New York, a newspaper clipping of Tom’s sentencing, and a ceramic dog from St. Louis. For each item, the film’s movement pauses for approximately three seconds, freezing the moving images into still photo-like ones. After looking at the newspaper clipping, Ma raises her right hand to her chin, a perfect mirror image of the gesture made by Lange’s “Migrant Mother” (i.e., the images are reversed to the viewer) and the movement pauses again for a brief moment. Then, Ma holds a pair of earrings up to her ears and the camera’s perspective shifts to a view that shows Ma looking into a square piece of a broken mirror framed by complete darkness. Here, the film’s movement stills for double the time of the other images, approximately six seconds. Even the flickering of light from the fire stops. The only illumination comes from an up-light somewhere below the actress. Ma is allowed to gaze at her portrait for a frozen moment in time. Similar to the previous pauses in movement, this “portrait” scene seems completely removed from the momentum of the rest of the scene. In it, the fire is gone, and the movement stops. When the camera returns to a larger view of the Joads’ kitchen, the broken mirror into which Ma has just gazed is nowhere to be found. The broken mirror is not a prop, but a photographic technique. It would not be probable for the Joads to have a mirror in their empty kitchen. This cinematographic method was simply used to create a portrait of Ma. As such, this image nods to the photographic portraits of Lange and the pause in narrative flow of Steinbeck.

Fig. 6. John Ford and Gregg Toland. The Grapes of Wrath Movie Still. Twentieth Century – Fox Film Corp. (1940)

Positioning of the Gaze

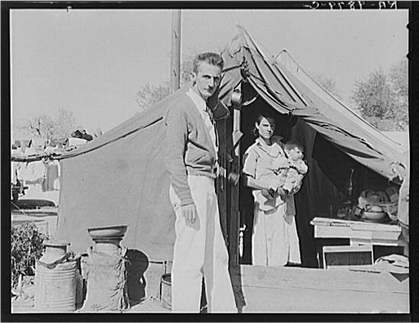

Besides Steinbeck’s and Ford’s allusions to Lange’s photography, the imagery in the novel and the film is similar to Lange’s photographic style. One group of notably similar images in the photos, the novel, and the film are images in which the migrant family is positioned within a tent, looking out. In all three types of images, the viewers’ and subjects’ gazes are situated according to the artist’s personal beliefs. Through subtle intimations within the composition of the images, the artist offers suggestions as to who should take action to help the migrants. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the comparative images of the shanty towns (i.e., Hoovervilles) and government camps.

Fig. 7. John Ford and Gregg Toland. The Grapes of Wrath Movie Still. Twentieth Century – Fox Film Corp. (1940)

In the film, just prior to the image of the family in the tent, Ford and Toland position the viewer as an outsider to Hooverville. As the Joads drive through the destitute camp looking for a place to set up, the migrants who inhabit the camp watch suspiciously. The scene is shot from the top of the Joads’ truck with the viewer looking down onto the existing campers. But while this scene could have easily turned into a spectacle of looking, Ford and Toland instead show the migrants returning the gaze. The migrants look coldly into the camera lens; thus, the gaze is turned on the viewer. Consequently, the viewer is being watched suspiciously and is situated as an outsider. In this sequence, positioned from the top of the incoming truck, the viewer is simultaneously distanced from the larger group of migrants and made to feel part of the Joad family.

As the men set up camp, Ma begins preparing what will be the family’s last hearty meal—stew. Starving children from around the camp all congregate around the pot of stew, which Ma is cooking outside her tent. The leader of the Joad family faces a dilemma: should she feed the hoard of hungry children or turn them away so her own family will have enough to eat? She decides to feed her family first, ushering them inside their tent, leaving the left-overs for the starving children. The Joads peer out from the tent with Ma standing in the opening between them and the children. It is at this moment that images from all three mediums converge in likeness.

Fig. 8. Dorothea Lange. Tom Collins, manager of Kern migrant camp, California, with migrant mother and child. (1936). Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, FSA-OWI Collection.

The film sequence in which Ma Joad is standing outside the make-shift tent as her family looks out portrays Ma as the mediator between the family and the outside world. In 1936, Dorothea Lange captured Tom Collins, a manager of one of the government camps, standing between the camera (and viewer) and a migrant mother with child. This effect produces Collins as the mediator between the migrant family and the outside world. These two images are nearly identical, the film again a mirror image of the photograph. In Lange’s version, Tom Collins, the government manager, is the mediator, and the viewer is situated through the subjects’ gaze. Tom and the migrant mother both look directly into the camera lens. Lange positions her viewers as the recipients of the gaze. They are made to feel as spectators—but spectators who have the power to change the migrants’ situation. The gaze is mutual and invited. Her image is addressed to readers of the Resettlement Administration reports; and the gaze implores action.

But, neither Steinbeck nor Ford translates this migrant/viewer situation into the government camp setting. Instead, they compose a more dramatic comparison between viewer and migrant from within the Hoovervilles. In chapter twenty, Steinbeck sets up the scene wherein the Joads arrive at Hooverville and Ma must decide whether or not to feed the starving children. As adapted in Ford’s scene, the Joads peer out from the tent with Ma as the intermediary. She tells her family, “Get in the tent quick” and then turns her back so she cannot see the children scraping for food.[18] Ford adapts this portion of the novel almost word for word from Steinbeck’s dialogue. But what is missing from the film is the interchapter material that precedes this chapter. In Steinbeck’s version, chapter nineteen creates sympathy for the migrants by demonstrating the basic human instinct for survival. The migrants do not steal for power, but simply because “the kids was [sic] hungry.”[19] And Hooverville does not represent one campsite but is indicative of a larger economic situation, for “there was a Hooverville on the edge of every town.”[20] Steinbeck warns the landowners who have ignored the changing economy and concentrated solely on the suppression of revolt instead of changing the situation that might instigate revolt. His warning comes in no uncertain terms:

And the great owners who must lose their land in an upheaval, the great owners with access to history […] and to know the great fact: when property accumulates in too few hands it is taken away. And that companion fact: when the majority of the people are hungry and cold they will take by force what they need. And the little screaming fact that sounds through all history: repression works only to strengthen and knit the repressed. The great owners ignored the three cries of history.[21]

Just prior to placing the Joads in Hooverville, Steinbeck offers a warning to the landowners as well as a battle cry for the migrants. He concludes the chapter by predicting an uprising, “Pray God some day kind people won’t all be poor. Pray God some day a kid can eat. And the associations of owners knew that some day the praying would stop. And there’s the end.”[22] For when the praying stops, the revolt begins. When the hope for change ceases, the necessity to instigate change takes over.

Steinbeck’s image demonstrates the disintegration of the migrants’ culture as a whole, Ford/Toland’s as the strengthening of one family of outsiders, and Lange’s as a plea for the government to take action. It is through the positioning of gaze that these different artists are able to situate the viewer according to their individual ideologies and purposes. Lange’s image invites a mutual gazing between migrant and viewer with the government camp managers as the intermediaries. Steinbeck, on the other hand, positions Ma as the intermediary between the family and the larger group of migrants. In the world he portrays, the migrants must resist repression and organize. Since the Joads (and by implication, other migrant families) lack male leadership, the women will have to take action and work to combine their families in one concentrated effort for survival. Ford and Toland turn the gaze inward on the Joad family. Since the viewer is made to feel a part of this unit, Ford and Toland create distance between the larger group of migrants and the singular family unit.

While the individual stylistic approaches and ideologies of Lange, Steinbeck, and Ford/Toland constructed images that are indicative of their individual beliefs and backgrounds, these images (primarily because of their similarities in visual representation) continue to be linked together. And, since these images are so commonly linked, a previously viewed image may return to the consciousness when triggered by like or related images. In some cases, the images might be mistaken for one another. For example, one of Toland’s film stills could be confused with Lange’s documentary photographs. But more commonly, these images mix in the subconscious, forming an overall image, or gestalt, wherein a person’s understanding of this era is understood by a montage of sorts, stored in memory.

Adding to the Gestalt

Contemporary artists continue to alter the existing narrative and photographic images, contributing to the public gestalt. For example, Ford used the popularity of Steinbeck’s novel in conjunction with his own perception of the migrant situation to create a widely popular film in 1940, which later influenced Bruce Springsteen’s musical lyrics for “The Ghost of Tom Joad” (1995)[23] as well as Rage Against the Machine’s remake of the song in 2000.[24]These musical lyrics, or “acoustic images,” likewise reach contemporary audiences who did not live through the Depression. Springsteen’s lyrics relate the story of Tom Joad to modern listeners as he brings the ghost of the most famous fictitious migrant back to life and relates his journey to modern listeners. He begins with the image of Tom that Ford and Toland made famous—the anonymous “everyman” walking along the deserted landscape:

Men walkin’ ‘long the railroad tracks

Goin’ someplace there’s no goin’ back […]

Families sleepin’ in their cars in the Southwest

No home no job no peace no rest.

Then, Springsteen brings the ghost of Tom Joad into modern day poverty, making Tom’s plight that of every man, woman, and child fighting to overcome displacement and prejudice:

Now Tom said, “Mom, wherever there’s a cop beatin’ a guy

Wherever a hungry newborn baby cries

Where there’s a fight ‘gainst the blood and hatred in the air

Look for me Mom I’ll be there

Wherever there’s somebody fightin’ for a place to stand

Or a decent job or a helpin’ hand

Wherever somebody’s strugglin’ to be free

Look in their eyes, Mom, you’ll see me.

The highway’s alive tonight

But nobody’s kiddin’ nobody ‘bout where it goes.

I’m sittin’ down here in the campfire light

With the ghost of old Tom Joad.

The highway that once held the rattle-trap automobiles of the migrants in the thirties has become, in the words of Springsteen, the highway of life. Springsteen relates how the contemporary viewer can integrate images of a time past into present experiences and understandings. For him, the memory/ghost of Tom Joad becomes a personal symbol of a universal struggle down a shared path. Springsteen’s chorus universalizes the story of Tom Joad’s story, and his lyrics are equally applicable to the public’s interpretation of these images.

The contemporary viewer is likely to encounter a mixture of images about the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, whether on the Internet, within a photo-text, on DVD or radio, or ininterpreted by readers, these images can intertwine, even becoming related in meaning or orientation. As Mitchell has asserted, they float freely apart from their original mediums within the memory of viewers, now existing as ghosts of the initial representations—ghosts that interact with other images. With PBS’s premier of The Dust Bowl, new audiences will once again encounter these familiar ghosts, captured, changed, and re-released as new forms of the iconic images.

Published on December 3, 2012.

Notes

[1] The Dust Bowl, directed by Ken Burns. (2012; Arlington, VA,: Public Broadcasting Service.), Television Documentary.

[2] Rob Lowman, “Ken Burns Documentary Recounts ‘Dust Bowl’ Tragedy.” Carlsbad Current-Argus, 15 November 2012. http://www.currentargus.com/ci_22005579

/ken-burns-documentary-recounts-dust-bowl-tragedy.

[3] Scott Simkins, “Steinbeck’s Critical Reputation.” The New Steinbeck Society of America. (24 April 2007). Accessed 17 November 2005. http://nssa.bsu.edu/.

[4] The Grapes of Wrath, directed by John Ford. (1940; 20th Century Fox). Film.

[5] See Peter Wollen, Signs and Meaning in the Cinema. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1973).

[6] Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

2006), 27.

[7] W.J.T Mitchell, What do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 92.

[8] See Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics. Trans. Roy Harris. (Chicago: Open Court, 1916).

[9] Mitchell, What Do Pictures What?, 85.

[10] Ibid, 2.

[11] John Bodnar, Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century. (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1992), 14.

[12] Laura Mulvey, Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image. (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2006), 28.

[13] Daniel Dixon. “Dorothea Lange.” Modern Photography, December 1952, 71.

[14] John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath. 1939. (New York: Penguin, 1992), 9.

[15] Ibid, 25-26.

[16] Vivian Sobchack, “The Grapes of Wrath (1940): Thematic Emphasis through Visual Style.” American Quarterly 31.5 (1979), 607.

[17] Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath, 148.

[18] Ibid, 352.

[19] Ibid, 323.

[20] Ibid, 320.

[21] Ibid, 324.

[22] Ibid, 263.

[23] Bruce Springsteen, “The Ghost of Tom Joad.” The Ghost of Tom Joad. Columbia, 1995.

[24] Rage Against the Machine, “The Ghost of Tom Joad.” Renegades. Epic, 2000.

Lauren Newton Glenn is a Doctoral Candidate of Film and Media Studies at the University of Florida. Her dissertation explores the pedagogical implications of the “moment” approach most commonly utilized by V.F. Perkins, Andrew Klevan, and Christian Keathley, and invoking the methodologies of Stanley Cavell and Ludwig Wittgenstein. By demonstrating different approaches via close readings of HBOs televised series Band of Brothers (2001), she posits that such methods provide open-ended opportunities for investigation of both “high” art films as well as the most representative of Hollywood productions. She regularly presents at a variety of film and media conferences and has initiated several on-going public forums on cinema studies within her community.