new worlds and dark traditions: back winding and forward propulsion in the woman who came back

Robert Spadoni

Click to view film clip in criticalcommons.org: “The opening sequence of THE WOMAN WHO CAME BACK (Walter Colmes, 1945)”

The Woman Who Came Back (Walter Colmes, 1945) is not a well-known film, but it might spark a feeling of déjà vu in a horror fan watching it for the first time. Admirers call the film “Lewtonesque,” tending simultaneously to make it equally clear that this is no Lewton film. For example, one writes that “as a minor-league Lewton homage, it rates an A for effort.” [1] Comparisons to the celebrated Lewton cycle owe to the film’s favoring of “suggestion” over explicitly showing the supernatural events depicted throughout most of its 68-minute running time, during which viewers are left in doubt as to whether the events are in fact supernatural. [2] More concretely and trivially, the first minutes call to mind the inaugural film in the cycle, Cat People (Jacques Tourneur, 1942), when a bus resembling the one that startles that film’s Irena—and carrying this film’s superstition-haunted protagonist, Lorna Webster—drives into the foreground. The associations triggered by the film’s opening do not, for a modern viewer, end there, for this bus will crash, and, improbably, one survivor will emerge from the water and stumble into the nearest town. The beginning thus situates us in familiar genre territory, staked out by Cat People at one end and by another beloved low-budget horror film, Carnival of Souls (Herk Harvey, 1962), at the other.

It might seem that we will need to brush aside such nostalgia-infused associations before we can view this film with any clarity, but I will argue the opposite, for this film, on its first release, evoked its genre to such a heavy extent that the effect, far from uncanny or strange, might have approached a soothing coziness. The Second World War had ended earlier that year, and it was perhaps assumed that the public had no taste for anything stranger and more threatening than this bauble of an ultimately reassuring film. (It turns out in the end that no supernatural events whatsoever have taken place.) How the film works to establish this familiarity is clearest in its first six minutes, during which the film also works, like any other, to propel its characters into fresh situations that will all eventually wind toward some kind of satisfying conclusion. And so the film underscores its generic affiliation with a vigor verging on self-consciousness while simultaneously attempting to serve up something new. The opening traffics in iconography, which sets us thinking about images. However, in both the “digging in” (emphatic genre identification) and “setting forth” (launching the narrative) energies expended in those minutes, two sounds play central roles.

A modest credits sequence—block white letters over a black background, overlaid with stock-sounding portentous music (scored by Edward Plumb) that promises a boiling pot of something ahead—sets the mood with minimal fuss, after which we come to the first image in the film: a painterly, aerial view of a town, superimposed over which is the town’s name.

Here we are introduced to two themes, stasis and repetition, that will characterize the larger film. (Actually, the repetition has been introduced earlier, with the film’s title.) First is the name of the town: “Eben Rock.” Eben is Hebrew for stone or rock, and so the town’s name works out to “Rock Rock.” [3] Second is a detail concerning the picture underneath. This image resembles nothing if not a painting, and the Currier-and-Ives effect is not inappropriate for our introduction to a sleepy New England hamlet (whose dark secrets we haven’t yet learned). And yet a bit of photorealistic movement has been added: wisps of smoke emerge from the chimney of the house in the image’s lower-left corner, something harder to miss after the superimposed letters have disappeared.

This image is static, unambiguously representational, yet something “real” and cinematographically “present” animates a small part of it. This film, likewise, will set into motion something distinctive and “immediate” against a comparatively large backdrop of the fixed, conventional, and quaintly old.

As we come up on this image, a voice-over begins that will carry through the prologue and lead us to the introduction of the main character, Lorna Webster. This is the first of our two important sounds. The sonorous and authoritative voice fills us in on the backstory that we’ll need to understand Lorna’s precarious position when we first meet her. She is descended from Judge Elijah Webster, who, three hundred years earlier, condemned eighteen women accused of witchcraft to be burned, including one—Jezebel Trister—who swore to return one day seeking revenge.[4] This commanding and informative voice bears a certain resemblance, in pitch and timbre, to that of Otto Kruger, who plays Reverend Jim Stevens in the film, a voice of reason, who, from his pulpit, will condemn the town’s superstitious thinking. The voice-over and the images that accompany it pack the prologue with exposition. Director Walter Colmes had earlier written radio dramas, and his comfort level with using the voice to carry a heavy load of narrative information is plainest here in the prologue, where he briskly sets the stage for the drama to unfold. [5]

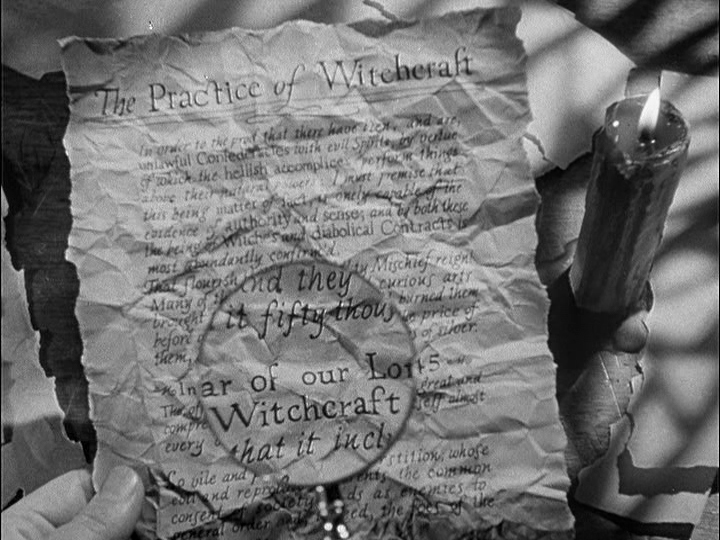

As the narration continues, we see Reverend Stevens in the town’s church crypt.

With a magnifying glass he studies papers, which the voice-over tells us are “faded documents that bear mute witness to the narrow bigotry of those settlers who brought to the New World the dark traditions they tried to escape in the old one.”

The Reverend, surrounded by trappings of antiquarian scholarship, makes a picture of the learned authority that will encourage us to trust him when he dispenses wisdom later on. But these surroundings—including stone arches, cobwebs, and dripping candles (although not so much the model ship)—could also be straight out of Dracula (Tod Browning, 1931). The introduction thus confers credibility on the character while simultaneously reminding us of the lore and iconography of a genre, which is something this film, here and elsewhere, heaps on nearly to the point of kitsch.

As the voice-over continues, we see glimpses of the town, with locations that will be important later highlighted, including the spot by Shadow Lake where an engraved stone marks the spot where Jezebel Trister was burned. Then, as the prologue ends, three shots incoherently situate the bus in relation to its next stop, in a way that I would like to suggest implicitly foreshadows a curious aspect of the narrative to come. In the first shot, the bus comes into the foreground and the camera pans left to track its movement across the screen.

The panning action continues across a wipe that reveals a shot of a sign for the town, bearing an arrow pointing right.

The next shot shows the bus continuing to move left.

This momentary inattention to screen direction inadvertently hints that this is going to be a film in which the forward line of the narrative’s development will in fact keep turning back in on itself, making a path that spirals ever inward.

An old woman flags the bus down. Cackling, she comes on board. When she’s told she cannot bring her dog on the bus, her reply, “This is no ordinary dog,” instantly reveals that the actress playing her is Elspeth Dudgeon, the woman who (billed as John Dudgeon) played the 102-year-old patriarch of the crazy Femm family in James Whale’s early horror milestone, The Old Dark House (1932). [6] The veiled face gives her away, too, but for me at least, the extremely characteristic voice, which sounds like the template for every old-lady-witch voice heard in movies and cartoons and TV commercials ever since, cements the association more quickly.

She sits beside the dozing Lorna, startling her. Lorna asks the woman if she is going to Eben Rock. The woman replies, “I lived there once, long ago. Now I am returning, as you are Lorna Webster.” Here a double recoiling action of the narrative is initiated— two women returning—two threads that later will intertwine. The woman reveals that she knows more about Lorna than her name. Lorna asks hers. We are approaching the climax of the sequence.

The hag answers Lorna’s question, in a shot in which her veiled face has been inexplicably darkened.

Here comes the first of a few shocks. She says, “My name is Jezebel Trister.” The lights have been brought way down—in this shot, which, like a miniature and self-contained stage, is making ready for a small coup de théâtre.

A reverse angle shows us Lorna puzzling over why the name “Jezebel Trister” should be so familiar. Dramatic music is rising. In the next shot, the woman lifts her veil while, unmotivated by anything diegetic, a light comes on to give us a good look at this first close view of her face. Another rapid alteration takes us back to Lorna and returns to the woman, who tilts her head back and issues a wild and triumphant cackle, following which she immediately lowers the veil again, like a little curtain, while her laughter fills the bus.

The laughter, or the occult forces behind it, causes the driver to crash through a fence and hurtle into Shadow Lake below.

The miniature effects work here is as charmingly artificial as the earlier image of the town. This is a tiny hand-crafted diorama of a place. It is a world where make-believe stories happen, and just about the only sort of place where this old lady’s laugh might seem scary.

This is the second important sound we have so far heard in the film. The first laid out liberal doses of backstory as it deftly got a modest little film underway. This second sound is iconicity through and through. Its source evokes a face that has been molded into latex masks and stamped into paper likenesses and hung on front doors at Halloween time. The only face to rival it might be that of the Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard Oz (Victor Fleming & others, 1939), but the face in this far less well- known film gives the Wicked Witch a run for her money. Fusing with the image and creating a more concentrated emblem of witch-ness is the sound. The mouth yawns open, but what issues from it is not speech, and it carries no story information. We have all heard this sound before, even if we have not seen this film. It is a witch laugh. It is the witch laugh, as certifiably off-the-rack as a cardboard jack-o-lantern or Day-Glo skeleton. [7] This film is doling out little scares that are pleasingly unscary, suitable for all but the smallest and most impressionable child. Rest assured, it seems to be saying, nothing you are seeing and hearing can ever reach beyond the borders of this snow-globe place and touch your world.

The bus sinks, and as we transition to the next location, the inn at Eben Rock, the film presents another image of enclosure. At first the shot is hard to read. An arch of some kind stretches across the top of the frame (easier to see in the video than the frame enlargement). We see a fire, and, beyond it, grotesque dancing figures.

The next shot reveals that we had been looking through a fireplace, out at some children in Halloween costumes. [8] A disheveled and gasping Lorna makes her dramatic entrance.

The stone that marks the spot where Trister was burned has been glimpsed earlier, during the prologue.

It is easier to construe this grotesque bas-relief representation as something calculated to deliver a mild shiver to a movie audience than as anything that would ever be erected to commemorate a terrible deed just outside a God-fearing town. Either way, the stone marks another spot as well, for both Trister (it would seem) and Lorna return to it and together go into the water. Only Lorna comes out, and when she begins to fear that Trister’s spirit is taking over her body, Trister returns yet again as the two figures appear to merge into one. At the climax, Lorna will return to this spot again and, a second time, plunge from a high place into the lake. Women come back in various forms and guises throughout The Woman Who Came Back. The action never strays very far from this marker, even while the action, like the portrait-lined staircase in the Webster manor, spirals backwards three hundred years into the past. And if genre films identify themselves as such by invoking conventions, then this film stages another kind of return as well. Two vocalizations, speech and laughter, establish and situate, although each in a different way. One communicates narrative facts while the other—irrational, pure spectacle for the ears—announces that we have crossed into the land of Trick or Treat.

Robert Spadoni is an associate professor in the English Department at Case Western Reserve University, where he teaches film studies. He is the author of Uncanny Bodies: The Coming of Sound Film and the Origins of the Horror Genre (University of California Press, 2007) and several articles on horror films and other topics. His website is robertspadoni.com.

Notes

[1] Tom Weaver, Poverty Row Horrors! Monogram, PRC and Republic Horror Films of the Forties (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1993), 287. Another notes that Cat People inspired a “trickle of Lewton-light” that included The Woman Who Came Back (James Marriott and Kim Newman, Horror! 333 Films to Scare you to Death [London: Carlton Books, 2006], 54).

[2] A writer on the film observes: “Obviously a disciple of the methods initiated by Val Lewton in Cat People (1942), Colmes works by suggestion throughout, not least in the fine opening sequence” (The Overlook Film Encyclopedia: Horror, ed. Phil Hardy [Woodstock, NY: Overlook, 1993], 90).

[3] Expository Dictionary of Bible Words, ed. Stephen D. Renn (Peabody, MA: Hendickson, 2005), 933.

[4] A character later in the film says the number is fifteen.

[5] References to the director’s radio career are in Edmund G. Bansak, Fearing the Dark: The Val Lewton Career (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1995), 382; and Michael H. Price and John Wooley with George E. Turner, Forgotten Horrors 3 (Baltimore: Luminary Press, 2003), 158.

[6] I consider this film in “The Old Dark House and the Space of Attraction,” Cinémas 20:2-3 (Spring 2010): 65-96.

[7] As a writer notes, “Dudgeon’s cackling crone is the story-book witch par excellence” (Jonathan Rigby, American Gothic: Sixty Years of Horror Cinema [London: Reynolds and Hearn, 2007], 280).

[8] Bansak calls the film’s disorienting introduction of these benign costumed kids “a ‘bus’-like device that anticipates a very similar moment in Jacques Tourneur’s 1957 Lewton homage, Curse of the Demon” (Bansak, Fearing the Dark, 381).