Affective Forces and Folds of Night:

Les Salauds/Bastards (2013) as Baroque Dark Matter

Saige Walton

The blame of the other, the blame on oneself, the guilt […] that’s what I really think is the texture of film. We are woven in a material that is made of hope, blame, and guilt, you know? —Claire Denis[1]

While Gilles Deleuze’s The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque is not one of the philosopher’s works that is specifically devoted to cinema, it is nonetheless rewarding for the study of cinematic affect. In her book Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality and Media, Giuliana Bruno argues for the fold as a textured philosophical concept that can speak to cinema as a site of material, mental and affective connection.[2] In this article, I will also consider the film-philosophical implications of the fold. Unlike Bruno, however, I return to The Fold to consider how Deleuze’s baroque fold might move through film. Concentrating on French director Claire Denis’s reinvention of film noir, Les salauds/Bastards (2013), I examine how Denis’s film is inflected by a dark baroque sensibility that folds cinematic affect together with materialist appeals to the body and to the mind.[3] Rather than proposing a new age or addendum to Deleuze’s categories of the movement-image and the time-image, I mobilise the baroque fold to speak to the embodied and thoughtful appeals of a baroque cinema.

To date, the elliptical sensuality of Denis’s cinema has often been read as an affiliate of the time-image. Yet it is Deleuze’s account of the baroque fold that speaks more particularly to the nocturnal yet glossy style of this film – its uses of colour, light, shadow, texture and movement – and to Denis’s reliance on darker kinds of cinematic affect. Throughout The Fold, Deleuze’s striking descriptions of historical baroque art and architecture evoke an aesthetic of formal and affective extremes that can be pushed cinematically. He writes of light slicing through shadows; the rawness of exposed textures; forms that act as forces upon the body; movements that occur in ascending and descending trajectories; and flesh rising up or falling back down into a deep darkness. In Bastards, Denis activates in film what Deleuze, with regard to seventeenth-century painting, calls the modulation of baroque “dark matter.”[4] Baroque dark matter is everywhere in Bastards as it is simultaneously deployed across the film’s formal, affective and conceptual levels. Without our own thoughtful and ethical response in turn, such darkness threatens to make bastards of us all.

Baroque Light in the Black

Set in contemporary Paris, Bastards marks another of Denis’s considered experiments with film genre. She derives both the film’s title and her male lead from Akira Kurosawa’s noir The Bad Sleep Well (1960) (translated in French as Les Salauds dorment en paix/The Bastards Sleep in Peace). Sections of the film were also adapted from the rape of Temple Drake in William Faulkner’s novel Sanctuary (1931).[5] Whereas previous genre efforts such as Beau travail (1999) had thwarted generic expectation by staging a military film in which “very little action” occurs, here Denis seems to revel in the various character types, plotting, gestures and attitude of film noir.[6] Noir suffuses the film’s atmospheric lighting, its urban mise-en-scène, its fatalistic mood and its incredibly bleak conclusion.

Following the suicide of his brother-in-law Jacques (Laurent Grevill), a supertanker captain named Marco Silvestri (Vincent Lindon) returns to Paris to comfort his sister Sandra (Julie Bataille). On the same night as the suicide, Marco’s niece, Justine (Lola Créton), is found naked and hospitalised because of her severe sexual injuries. Sandra informs Marco that a prominent billionaire, Eduard Laporte (Michel Subor), is behind these events and is also responsible for the bankruptcy of the family business. With plans of revenge, Marco moves into the building where Laporte resides with his mistress Raphaëlle (Chiara Mastroianni) and their young son, Joseph (Yann Antoine Bizette). He pursues an affair with Raphaëlle to glean further information on Laporte. Marco’s niece eventually commits suicide and Marco himself is shot dead by Raphaëlle during an altercation with Laporte. In the film’s coda, Sandra plays a videotape recording that reveals both the source of Justine’s injuries and the likely cause of her and her father’s suicide.

Given its mystery/revenge plot, its intertwined themes of sex, money, power and corruption, its calculated uses of film style and its recognisable character types (the male victim/hero; the bastard patriarch; and the femme fatale), Bastards is entrenched in many of the iconographic signatures of American film noir. At the same time, Denis transforms the noir of the past by melding its urban hostility together with what Rosalind Galt calls the hostility of contemporary transnational capitalism. In Galt’s reading, the titular bastards of the film link Denis’s “cinematic vision with exploitative social relations […] as an affective lens through which to view and think capital.”[7]

While there is little doubt that greed, sexual exploitation and capitalism are at the very centre of Bastards, I am more concerned with how Deleuze’s baroque fold might provide us with another affective lens of interpretation for this film. Moral darkness and blindness (as this involves obscured, darkened or complicit vision) are crucial to the plotting of Bastards. As Cathryn Vasseleu details in her book Textures of Light, light has long held metaphoric and philosophical associations with the pursuit of truth and knowledge and with the certainty of stable spatial, visual and physical coordinates. As she puts it, “seeing light is a metaphor for seeing things in an intelligible form.”[8]

Rather than seeing in the light, Bastards begins in near total darkness. The opening images refuse both the clarity of vision and assured spatio-temporal coordinates. As befits noir, the film opens at night with the heavy textures and sounds of pouring rain. A close-up of this rain falling in the foreground is so thick with water that it creates the effect of a watery curtain obscuring the background of the image [Figure 1].

After a few mournful bars of the Tindersticks’ music seep in, the film cuts to an unidentified businessman walking about an empty office space. The camera drifts up the side of the building to take in the glistening effects of the urban streetlights bouncing off the building’s watery façade. A sharp cut displays two unexplained objects on top of an office desk: a blank white envelope and the edge of a woman’s tan shoe. With his back to the camera the man proceeds to put on his suit jacket before leaning out one of the windowpanes and looking solemnly out at the rain. The camera’s vision then moves away from the businessman. It traces the path of the rainwater down the side of the building before coming to a curious halt at the pavement.

In the next cut, we return to the same setting. Time has elapsed and the sudden downpour has ceased. Where the camera previously left off, a corpse lies covered by a white sheet. The once isolated and darkened industrial surrounds of the building are now filled with police and ambulance workers, their vehicles lighting up the night. Interspersed with the discovery of the body is the haunting imagery of a young girl. She walks out of the darkness and into the centre of the frame, naked except for a pair of very high heels [Figure 2]. As she turns, light catches the edges of her body, revealing darkened smears of blood across the backs of her legs. In a Sadean twist that hints at the film’s concern with sexually charged violence, we soon discover that this girl is named Justine. She is Marco’s niece and the businessman who just committed suicide is her father, Marco’s brother-in-law.

From the first scenes of the film, then, Justine and her father are implicitly linked through editing and connected to different material objects: a suicide letter and sets of women’s shoes (an important motif for this film, and one I will return to).

Justine’s appearance signals yet another of Denis’s evocative gestures towards noir. Her arrival recalls Christina running down a highway at the start of Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955): another mysterious and near-naked woman who sets the noir plot in motion. However, Denis chooses to return to Justine and her high-heeled path through the streets three times: in long shot; in mid-shot; then, finally, in close-up. Each time she adds further horrific details that ground Justine’s actions in a progressively clearer sense of plotting, time and causality. Soon after Justine’s first appearance, for instance, Sandra mentions that she has previously filed complaints against Laporte with the police. We also learn from one of the hospital doctors (Alex Descas) that Justine has sustained sexual injuries so severe that her vagina might be in need of surgical repair. Significantly, the inclusion of a graphic close-up of Justine’s blood-soaked thighs is delayed until after these crucial revelations. As such, Denis’s calculated repetition of Justine’s walk and her delayed frontal close-up of Justine’s wounds “ensures [that] we look – really see – her bleeding body.”[9] For Denis, Justine’s walk through the streets is the leitmotif of the film. It is her image of “that girl who comes from Faulkner. She’s young. She’s beautiful. She’s terribly wounded. And yet she seems solid. She’s walking with her head high. In those moments, she’s not a victim […] she’s transporting us somewhere.”[10]

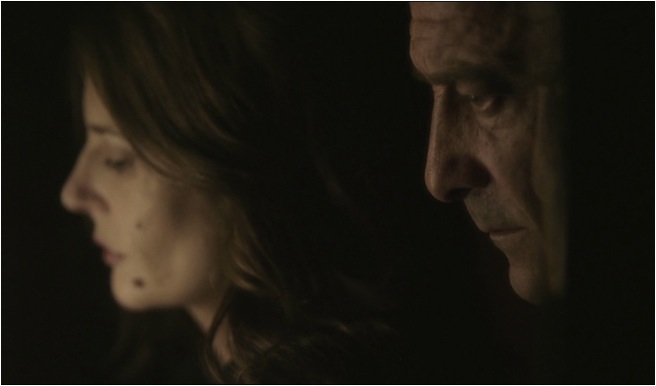

Precisely where is Justine transporting us? Given Denis’s many allusions to noir, it is hardly surprising that high-contrast lighting together with night scenes should feature so prominently in Bastards. At the same time, noir is not sufficient to accommodate this film’s affective force and what I am calling its folds of night. Much of the critical commentary that has circulated around Bastards has referenced the film’s “dark beauty” without attaching its formal and affective darkness to any particular aesthetic.[11] Only Nikolaj Lübecker’s reading has observed that there is something “almost baroque” about Denis’s “darkest and most disturbing film to date”, especially in terms of how the film’s subject matter plays out against the sleek look and feel of Agnès Godard’s cinematography, artificial imagery and a dissonant electronic score.[12] Negative affects intertwine with lush and captivating stylistic effects. For me, what is so striking and so characteristically baroque about Denis’s film is its portrayal of a darkness that also does not appear fully black. Often, the film’s darkness glows as if its images of flesh were coated with a thick glossy veneer or sheen [Figure 3].

In his Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, Deleuze asserts: “light would be nothing, or at least nothing manifest, without the opaque to which it is opposed and which makes it visible.”[13] In the relational cohesion of classical cinema – Deleuze’s order of the movement-image – “light is movement […] one and the same appearing.”[14] Rather than being opposed to darkness, light enters into concrete relations of contrast, shading or mixing in order to be seen. Even in the sensory-motor schema of the movement-image, there is always some degree of darkness or shadow in the coordination of light into perception, action and movement. How, then, does the darkness of Bastards help to coordinate baroque action and movement in film?

Filmed with the Red Epic camera, Bastards marks Denis’s first collaboration on digital. According to Denis, the digital is better suited to the urban because it lends images a cool visual temperature. At the same time, she has commented on how it was “very hard to film in the shade digitally” with regard to Bastards.[15] When shooting close-ups of faces, the flesh of the body or in the shadows (all sensuous hallmarks of Godard’s cinematography for Denis), the digital would add in the light.[16] Full darkness could not be achieved because of the film’s digital production technologies. What resulted instead was a dark light. Such an iridescent black is also present in historical baroque art (though it is achieved through very different materials and through careful layering).

In The Fold, Deleuze’s understanding of the art of the historical baroque age is “inseparable from a new regime of light and color.”[17] In fact, he identifies the major “baroque contribution” as the use of a dark red-brown background instead of a white primer for the canvas.[18] This is the background upon which seventeenth-century artists painted “the thickest shadows” and experimented with effects of shading.[19] Crucially, the dark base does not negate the light, nor is it configured in opposition to it. Baroque light ensures that clarity “endlessly plunges into obscurity” and yields striking effects of colour, movement, surface materiality and depth to its darkness.[20] To quote Deleuze: “Things jump out from the background, colors spring from the common base […] figures are defined by their covering more than their contour […] this is not in opposition to light.”[21] Here, we should note Deleuze’s emphasis upon thickness, materiality and depth in baroque art, such as the painting of “thicker and thicker shadows” or depictions of “cavernous matter.”[22]

As The Fold does not focus on cinema, Deleuze does not indicate how the baroque regime of light and colour might operate in film. This is not because Deleuze is particularly attached to the seventeenth-century European baroque and its original forms. As with the philosophical invention of concepts, Deleuze sees the best kind of baroque scholars are those who invent concepts that are commensurate with the baroque’s existence.[23] In The Fold, Deleuze himself reinvents the baroque as far more than a historical moment or even an aesthetic style. He understands the baroque as a trans-historical phenomenon that boasts an identifiable “operative function […]. It endlessly produces folds.”[24] If, as Deleuze insists, baroque folds can be discerned across the contemporary works of “architects, painters, musicians, poets, and philosophers,” I think we are justified in extending the baroque fold to film as well.[25]

In addition to noir, Denis reactivates the formal sensibility of a dark baroque in Bastards. As Lübecker observes, the film’s highly aestheticised images can look very “non-filmic.”[26] For Lübecker, these images have “no depth” and make for a series of beautiful albeit “slippery, flat, texture-less surfaces” that the spectator watches “as if they were placed behind a glass pane.”[27] And yet, though the film’s images can indeed appear planar – such as with the opening shots of the rain – I would hesitate to call them either flat or textureless. Attending to the sleek surface of the digital image, Lübecker does not take into account the couplings of the surface with intimations of depth that recur throughout. Often the film’s dark light can appear vast and engulfing. In many of Godard’s shots, softly lit flesh glows against a glossy dark background whose contours cannot be determined and seem to stretch on indefinitely [Figure 4].

If there is a non-filmic look to Bastards, it has much more in common with the dark light, layering and thick shading of historical baroque art, wherein light “slides as if through a slit in the middle of shadows.”[28] Furthermore, Denis’s and Godard’s digital filmmaking automates a light in the black that reprises similar effects of an iridescent and suitably baroque darkness.

Nevertheless, the events of Bastards do not only take place at night or in the midst of thick shadows. Much of the film is quite chromatically bland. It is tinged beige, grey, slate, cream or off-white, as if echoing the film’s concern with capitalistic corruption and hidden secrets behind visually unassuming façades. When colour is used, it perceptually erupts through an otherwise drab mise-en-scène, as with the glaringly bright blue cake that Raphaëlle bakes for her son, or Marco’s vengeful fantasies of Joseph’s crashed yellow bicycle, shining in the night. As Deleuze reminds us, there is not a simple one-to-one correspondence between a particular colour and a particular affect. Rather, colour is “the affect itself, that is, the virtual conjunction of all the objects which it picks up.”[29] Like the amorphous spread of shadow that loosens a clear sense of spatiality, Deleuze associates colour with the indeterminate spaces of the any-space-whatever and with the properties of film affect. Drawing a highly cogent parallel with painting, he suggests that cinema can also partake of colour’s absorbent function. What Deleuze calls the colour-image in film affectively “absorbs all that it can: it is the power which seizes all that happens within its range, or the quality common to completely different objects.”[30] Bearing the affective and dispersive qualities of the colour-image in mind, we can now examine how colour also cues us in to the dark baroque of Bastards.

Halfway through the film, Marco journeys with Sandra to an isolated farmhouse to pay off two of the family’s creditors working for Laporte, Xavier (Grégorie Colin) and Elysée (Florence Loiret-Caille). Upon his arrival at the farmhouse Marco notices heavy nightlights and the presence of security cameras fixed to the building. While vacant and seemingly unremarkable during the day, the farmhouse is clearly set up for nighttime activity. After the lights are turned on inside, the camera pans across the remnants of the private parties that have been held in the room. We see a chair that is raised on an odd makeshift stage in the corner, empty champagne bottles and strewn glasses. The colour red predominates: it appears in the sleazy red leather bed that is visibly stained with semen; in a scarlet velvet-curtained backdrop behind the bed and in washes of red light from a nearby red lamp, connoting prostitution. Marco then notices equipment in the roof for camera recording and a floor that is littered with bloodied corncobs. Dark red also coats the fingernails of the pregnant Elysée while ominous traces of dried blood can be seen encrusted upon the surfaces of the corn. Suddenly aware that the farmhouse and its objects are somehow connected to his niece, Marco tackles Xavier before rushing off to the hospital. Red then chromatically spills out from one scene to the next. It connects the illicit space of the farmhouse to the hospital in which Justine is housed, tinting the hospital for the first and only time in a pinkish red wash. Denis then cuts to a scene of young laughing children as Raphaëlle drops Joseph off at school in the morning.

As Deleuze comments, the colour-image can absorb “not only the spectator, but the characters themselves, and the situations, in complex movements.”[31] In Bastards, colour creates mobile affective connections and correspondences between different characters, objects, bodies and spaces. Uneasy feelings filter through the disparate sites of the farmhouse, the hospital and the school, associating them with the disturbing and the sinister. Like the pervasive use of red in the farmhouse, there is something that feels off about all the film’s colour-images. Colour brings together what should not belong together: a broken or smashed-up child’s bicycle; a visibly synthetic cake; and a bloodied corncob (another reference to the rape that occurs in Faulkner) [Figure 5 and 6]. Given Denis’s own recurring concern with familial dynamics and domestic portraits, it is surely not a coincidence that Elysée appears heavily pregnant or that the use of red taints even the images and sounds of laughing children.

Primary colour-images (yellow, blue and, most noticeably, red) are all linked either directly or indirectly to images and ideas of children. The various objects and spaces with which children are associated also appear broken down, chromatically ill-suited or violent. In Bastards, it is not only dark light that conveys the film’s unpleasant affects and its moral darkness. Anxious feeling pervades Denis’s colour-images to indicate how the bastards exploit their own children or the children of others as sources of financial, emotional and sexual capital. Awash with red once more, the coda confirms our increasingly dreadful suspicions as to how Justine’s teenage body has been financially traded, emotionally abused and physically violated. In one of the most disturbing instances of the ethical and affective darkness at the heart of this film, the coda reveals Jacques (overseen by a voyeuristic Laporte) in a sexual situation with his daughter at the farmhouse. If this recording were not sufficient testament of complete and utter familial breakdown and betrayal, it turns out that Sandra knew about these events and that she herself may well be the other participant in the sex/torture tape.[32]

Baroque Folds as Affective Force

At this juncture, it may seem as if we have strayed from the sensibility of the baroque, so let me invoke the work of the French philosopher Christine Buci-Glucksmann. She has also observed how we can inscribe a definite sense of “horror within [the] beauty” of historical baroque forms.[33] In fact, she sees dark light as similarly central to baroque aesthetics. Identifying “a black that doesn’t look black for it is just as light as it is dark,” she describes the baroque artwork as emitting a dark luminosity or an “irradiated dark clarity.”[34]

Baroque black backgrounds shimmer. Intriguingly, however, what lends a sense of illumination to these backgrounds is not white but red. In the paintings of artist Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, for instance, it is the depth, richness and vibrancy of red that tempers the darkness. Spurting blood or tactile garments and drapery are painted with a pronounced red that conveys the vitality and flow of life. At the same time, Caravaggio’s spectacular scenes of violent action and martyrdom capture life as it is ebbing away. In works such as Judith Beheading Holofernes (1598–99), bodies “die against the backdrop of [red] curtains just as in the theatre.”[35] Sensuously conjoining the forces of life and death, red lends light to Caravaggio’s blacks and a sense of volume, depth and real “substance to his bodies.”[36] The rendering of this red is “so intense, so alive, so bloody and bleeding” that even painted “linen drinks up.”[37]

Again, Buci-Glucksmann is concerned with historical baroque art and literature and not with the specifics of a baroque cinema. Nonetheless, we can extend her claims for baroque horror and an affectively absorbent red (a red that materials drink up) to the corporeal violence of Bastards. As Deleuze rightly cautions in The Fold, however, Buci-Glucksmann’s baroque hinges upon a theatrical dialectics of seeing and gazing. Vision alone is not sufficient to accommodate the complexity or the sensuality of baroque form and thought.[38] For Deleuze, the “operative concept of the Baroque is the Fold: everything that it includes, and in all its extensiveness.”[39] Likewise, for this article it is Deleuze’s baroque fold that does full justice to the sensuous yet affectively disturbing nexus between light, shadow, colour and physical brutality that underpins Bastards.

Significantly, it was after his engagements with cinema and with the work of Michel Foucault that Deleuze was to re-evaluate the baroque. In this regard, the fold offers us much more than just a sensuous figuration of baroque aesthetics. At the crux of Deleuze’s baroque is a movement between what the philosopher calls the immanence of “pleats of matter” and immaterial “folds in the soul” (the life of the mind).[40] Drawing upon historical baroque architecture, Deleuze allegorises the movement between body, mind and world as the Baroque House. On the lower floor of the House, small openings let in the light; this is the realm of the senses. On the upper floor of the House, there is a darkened room or chamber that is without windows. This enclosed space also contains drapery “diversified by folds”; this is the realm of the soul/mind.[41] The two levels of the House are separate but united by the fold that moves between them, “arching from […] two sides” and bringing the surfaces of matter and mind together like a creased and perpetually moving cloth.[42]

In what remains of this article, I want to read the dark baroque as not only pertinent to the film form of Bastards but also to the film’s affective force and its stirring of thought. As Galt notes, “particular visual strategies” in the film such as colour and texture “suffuse the screen with sexual threat.”[43] These visual strategies resonate with the conjunctions of life and death that recur in the dark baroque. Given its implied underground trafficking in pornography, prostitution, sexual violence and torture and its explicit depictions of suicide, incest and murder, the physicality of Denis’s film bears much in common with the darker strains of what has come to be known as the new European Extremism or the contemporary French cinema of sensation. While some of this content has a definite lineage in American film noir, it is presented in temporally prolonged, graphic and confronting terms in the genre reworkings of these movements.[44]

As indicated by Bastards, however, corporeal extremism can be organised by very different aesthetic modalities. In this regard, Bastards is better recalibrated as an instance of baroque extremism in film—in the sense that Patricia McCormack has usefully deployed the baroque. In her book Cine-Sexuality, McCormack draws upon Deleuze’s fold to argue that the baroque persists as a heightened affective style in film. This affective style foregrounds the matter and materiality of images through extreme scenarios of gore and horror, the staging of perverse desire or other viscerally embodied spectacles.[45]

While baroque extremism is not formally abstract, it abstracts us from a safe corporeal distance from the image and often from more pleasurable kinds of cinematic affect. In McCormack’s interpretation, baroque images will also “abstract the body and desire” from what is considered culturally acceptable or desirable.[46] In turn, they affectively abstract us, as viewers, from those norms. Though she is correct about the baroque’s interest in affective extremes, McCormack somewhat reductively detaches the baroque from all standards of realism. In her terms, the baroque affective style can only occur in fantastic, supernatural or impossible scenarios. While attuned to its nihilistic attitude and its negative affects, Lübecker’s take on the baroque qualities of Bastards also mistakenly severs the baroque from any and all indexicality.

Deleuze’s baroque fold and the history of dark baroque forms suggest other possibilities for film. As Deleuze points out, baroque matter “that reveals its texture becomes raw material, just as form that reveals its folds becomes force.”[47] In Bastards, Denis slowly and quietly reveals the rawness of what has happened to Justine. Through formal repetition and a foregrounding of different surface coverings, objects and textures, it seems as if the materials of this film have absorbed not only bodily fluids but also a darkened affective atmosphere of human suffering and pain [Figure 7].

Throughout, the camera lingers on marked-up human flesh and on the surfaces of objects. Consider the delayed close-up of Justine’s blood-streaked legs or the silent yet unnerving close-up of the bloodied corncob, its silken stalks so queasily evocative of human hair (what is that?) [Figure 8]. Denis uses both human and non-human forms of materiality to convey the exploitation of Justine, experiences of sexual violence and pain. Amidst glossy black and/or red backgrounds, figures come to be “defined by their covering more than by their contour” if we recall Deleuze’s thoughts on dark baroque painting.[48]

As art historians such as John Rupert Martin have observed, the historical baroque revelled in a graphic flesh-and-blood realism in the arts. The age brought the thinking of abstract ideas such as divine suffering back down to earth through calculated appeals to the body, affect and sensation.[49] While we are very far from religious or sacred subject matter in Bastards, we are not far from depictions of an extreme baroque physicality. For the affective extremes of the baroque and a baroque cinema, realism is gauged in and through the experiential realism of the body—no matter how unrealistic and/or abstract the subject matter. If many scenes place bodies in brutal and culturally unacceptable situations such as incest, sexual violence and torture, Bastards grounds its images and sounds in the realism of the body as well as chillingly real-world scenarios (monstrous greed, the patriarchal exchange of women and bourgeois capitalism). In an attempt to stave off financial ruin, Justine’s body is traded to Laporte to pay off the Silvestri business debts. Desperate to be reunited with her son, Raphaëlle shoots her lover rather than Laporte to maintain her own familial, financial and domestic security.

In Surface, Giuliana Bruno aptly observes that cinematic “affects and sensations unfold within us, closely knit to the activity of thinking.”[50] For Bruno, Deleuze’s fold provides us with a powerful means of “thinking the visual in a material way” that also resonates with inner psychic life.[51] Calling attention to the surface of the image, she invokes Deleuze’s concept of a “texturology” in The Fold to argue for cinematic images as being similarly and sensuously clothed.[52] I greatly appreciate Bruno’s arguments for the materiality of the image together with her emphasis upon cinematic affect as being intimately bound up with thought. Nonetheless, she is not concerned, as I am, with identifying baroque forms of film and their affects. Furthermore, in divesting the fold of its historical baroque clothing in Deleuze’s thought, she inadvertently strips the fold of some of its crucial formal features. As it moves between the sensate and the thinking, Deleuze’s baroque fold is not only bound up with the immanence of texture but also with the intermingling of darkness and light (dark light). Mind and matter are inseparable for the fold, just as light and shadow are in the artistic practice of chiaroscuro. In these terms, Deleuze’s texturology is not just a plea for the material clothing of the image but for a specifically baroque “conception of matter.”[53] Invoking the art of Caravaggio, Deleuze connects baroque matter and materiality to dynamic and mobile transitions of affect, light, shadow and colour. To quote Deleuze: “As a painter of textures, Caravaggio modulates dark matter with colors and forms that act as forces.”[54]

In The Fold, Deleuze connects light and shadow with the formal, affective and conceptual momentum of upward and downward movement, respectively. When he touches on historical baroque painting, for instance, he writes of bodies that ride on high “yellow folds of light” or those that are “tormented by their own weight […] bending and falling into the meanders of matter.”[55] These two levels – the upper and the lower, the light and the dark – can seep into each other or reverse, for they are separated only by “a thin line of waters: the Happy and the Damned.”[56] For my purposes, it is significant that Deleuze’s dark baroque also suggests a dragging of aesthetic form downwards through the depiction of bodies that slip, stumble and fall into matter. The loss of stable spatial and visual coordinates can be connected to what Roland Barthes once aptly described as the “funerary” tendencies of baroque forms, evident in recurring themes of death, dying and corpses as well as scenes of violent action.[57] Affective forces and folds of night overwhelm bodies in the dark baroque, causing them to fall not only into matter but also into their graves.

In Bastards, a downward trajectory towards death is set in motion from the beginning. Pensive and weighted imagery opens the film, from the heavy falling rain to intimations of Jacques’s suicidal fall through the window or the camera’s own move to the ground. Throughout, Denis relies upon suggestions of gravitational weight and bodies falling to orchestrate the film’s downward momentum as a grave-bound movement. Descending motion is stylistically evoked through the film’s recurrence of overhead shots or the use of vertically oriented points of view that weigh down upon various characters, as if pressing them into the earth [Figure 9]. Allusions to death even appear in the background of Laporte’s luxurious Haussmann apartment [Figure 10].

A gravitational pull to earth is also symbolically encoded into the film’s motif of sets of women’s shoes. Justine’s naked appearance at the beginning of the film ushers in the larger significance of women’s shoes throughout. While the manufacture of women’s footwear is the purpose of the Silvestri family business, the single shoe that sits atop Jacques’s desk provides an early indication that Denis’s film is anything but a fairytale.

Throughout, shoes can be seen suspended as abstract signs and allegorical symbols [Figure 11]. They appear as ghostly objects that are detached from the bodies of real women or as an ugly surplus, piled up into a heap (much as women are expendable and interchangeable objects for the bastard Laporte) [Figure 12].

Figure 12: Shoes substitute for the bastardly view of women as surplus. Bastards (Claire Denis, 2013)

Denis’s repeated emphasis on shoe-clad feet functions as an important metonym for her characters, such as with her attention to Raphaëlle’s shiny, expensive footwear, or her refusal to portray Justine as a barefoot victim. Similarly, shoes serve as vital clues that indicate who is corrupt or complicit in Justine’s injuries. When Marco first takes Sandra out to the creditors, Denis subtly holds on Sandra’s gestures in the car. Sandra is seen “changing her shoes and putting boots on […] she knew that there was dirt there” at the site of the farmhouse, having helped to organise the prostitution of her daughter there before.[58]

Let us consider another telling sequence that relates to the dark baroque, especially in terms of how it pulls bodies and aesthetic form downward into the dirt of the grave. Haunted by the loss of her father (at once her lover and her abuser) and by the trauma that she has endured, Justine eventually flees the hospital. In the penultimate scene of the film, she deliberately crashes the car she is riding in with Xavier and Elysée. As the car hurtles down the highway, the brightness of human flesh stands out against an atmospherically thick and volumetric darkness [Figure 13]. Initially shot close to bodies inside the car, the arresting sensuality of the scene and its baroque dark light soon gives way to anxious feeling and to extreme violence.

Against sounds of the car’s revving engine, the film’s hypnotic electronic score rises, replete with wailing sounds and breathy cries. Justine moves across to replace Xavier in the driver’s seat and the film cuts to a view of the tarmac lit up by headlights, followed by an exterior view of the car. Significantly, we have seen this highway and a car on it before—the first time that Marco journeyed out to the farmhouse. This time, however, it takes on associations of dread through the pulsating score, the bright red taillights that puncture the night and the progressively unsteady car. Daytime spaces, atmospheres and settings are repeated and varied in their malevolent nighttime counterparts [Figure 14].

Justine suddenly turns off the car’s lights, flooring the accelerator. The sounds of the car’s engine and the film’s score build in volume, energy and intensity before Denis finally unleashes the full affective force of Justine’s final joyride. She cuts from Justine’s hands at the wheel, twisting the car off the road, to near silent imagery of the fatal car wreck. The vision of the camera coolly pans across the metal debris of the accident and the bloodied bodies that have been carelessly flung into the dirt or through the windscreen. The twisted and torn metal surfaces of the car function as a powerful substitute for the broken and torn bodies housed within, especially that of Justine [Figure 15]. She has, however, managed to take some of the film’s bastards “down” with her.

In words that recall Deleuze, Denis herself has described this sequence as moving from dark yet seductive impressions of bodies flying and caught up in the youthful “flow of life” to a statically held image of the wrecked textures of the car.[59] As is befitting of the dark baroque, life gives way to the grave.

Coda: Baroque Folds as Affective Thinking

Having illustrated some of the formal and affective features of the baroque in Bastards, I want to close with a brief examination of how this film reverberates with Deleuze’s fold at a conceptual level. Like Deleuze’s articulation of the fold as movement between mind, body and world, Bastards brings together its literal and figural darkness with violent extremes to further affective thinking. As Elena del Río has helpfully established, Denis’s films often contain a privileged scene that condenses the activity of her characters, the film’s overarching themes and the film’s own powers of affection.[60] Herein, image, affect and concept become one. In Bastards, this scene is unquestionably the film’s coda.

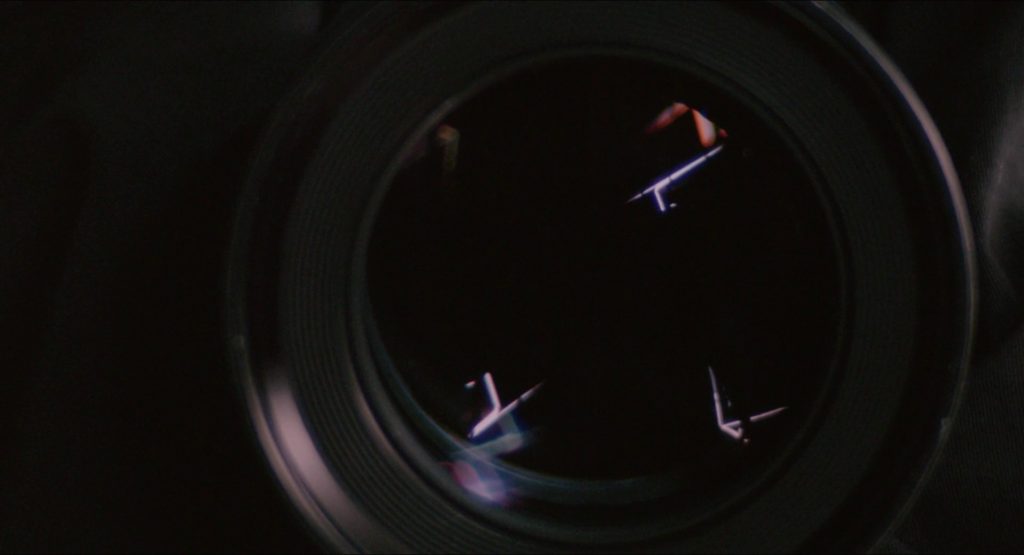

In revealing the previously hidden contents of the tape recording, Denis did not want the imagery of the coda to appear “ugly” but “clandestine.”[61] While also shot on digital, the coda has none of the darkened gloss that the Red Epic lent to the rest of the film. Its images are noticeably grainy and heavily textured, mimicking the low-fidelity look of surveillance footage, exploitation cinema and low-budget pornography. The coda begins with a close-up of a camera filling the frame, light bouncing off its lens, accompanied by an electronic reworking of the song “Put Your Love in Me” by the English band Hot Chocolate.[62] Obviously, the reveal of this camera cannot be the same camera that is caught up in the very activity of filming [Figure 16]. Questions immediately arise: Who is filming? Are there multiple cameras and multiple tapes? If so, what are their contents? While providing us with some degree of plot resolution, the coda prolongs the interpretative possibilities of this film into ever-widening and nefarious circuits.

An overhead shot follows the close-up of the camera. This shot very clearly reveals Jacques with another woman (Sandra?) and a naked Justine lying on the farmhouse bed while Laporte watches on [Figure 17]. Formally, the coda is organised along two now familiar axes: the upper and the lower, the dark and the light, the happy and the damned. Bodies are either seen from above and very brightly and intelligibly lit, or bodies are seen from below and positioned alongside those taking a perverse pleasure in the scene. The horizontal axis is suffused by the colour red, by darkness and by shadows.[63] In an attempt to render some of these images even more opaque, the coda footage was deliberately shot through a mirror. As a result, it is sometimes so difficult to determine the identity of bodies in the tape that Jacques and Laporte become interchangeable in the dark—both corrupt as well as corrupting patriarchal father figures.

Figure 17: Terrible secrets: the coda incites feeling as well as thought. Bastards (Claire Denis, 2013)

As McCormack comments, in many baroque images in which we dwell in the dark, “the point of illumination […] is also the moment of horror.”[64] For all its revelation of artifice such as the inclusion of camera or the radical disconnect between the film’s images and its music (“I want to be in heaven”), Denis’s artifice does not lessen the horror of the coda. Contra Lübecker’s claim that “baroque images (and descriptions) are meant to pull away from the indexical” such that Denis “tries to mark a distance from reality”, I would assert that the entire purpose of the film’s coda is to shock, to incite feeling and to drive home the reality of the body.[65]

In diegetic terms, the tape is meant to be in the process of being watched by Sandra and the doctor, yet Denis never interrupts the affective impact of the coda by cutting to their reactions. While Laporte is sometimes just discernible, the most illuminated portions of the coda serve as charged conduits for inciting feelings of disgust, revulsion and horror. We see Justine and her father gazing at each other. Justine holds her hands out to him, inviting him onto the bed, while Jacques gently strokes his daughter’s face before picking up the corncob. Crucially, at this precise point, the camera veers right and moves its vision off into the darkness—as if the film itself can no longer bear to look at what is about to happen (and what already has).

In Cinema 2: The Time-Image, Deleuze once invoked the “Cartesian Diver in Us” to describe the spiritual automaton of cinema as it instigates movement in the mind.[66] In The Fold, he invokes the Cartesian Diver again with regard to the baroque fold and its movement between matter and mind. To quote Deleuze: the “reasonable soul is free, like a Cartesian diver, to fall back down at death and to climb up again at the last judgment. […] body and soul are inseparable.”[67] Blind to the truth and to the irreparable damage that they do to others, the bodies of Bastards repeatedly fall down into moral darkness, corruption, depravity and death. In the wake of Marco’s and Justine’s deaths and the suggested cycle of abuse that is likely to continue with the bastards who survive, it is left to us as viewers not only to feel, but also to think and to provide our last judgment on all that has occurred. Semi-detached from the main plot of the film, Denis’s bleak conclusion provides us with no set ethical answers. Through its revelation of terrible familial secrets, its emphasis on shocking corporeal extremes and its interpretive ambiguity, the coda brings the force of cinematic affect together with thought. By opening up more questions than it answers, the baroque design of the coda prompts thought and ethical deliberation long after the immediacy of feeling has subsided.

As Deleuze tells us, in the baroque “the coupling of material-force is what replaces matter and form.”[68] Material-force gives rise not only to new bodily affects but also to new folds of thought (the primal forces of the baroque are its affective “folds in the soul”).[69] Given its formal and affective darkness as well as its thoughtful provocations, Bastards can be approached through alternate Deleuzian concepts than the movement-image and the time-image. As I have suggested, Denis’s revisioning of noir is also steeped in dark baroque matter. From beginning to end Bastards is a film that is best read through the aesthetic form, the affective thinking and the material-force of Deleuze’s baroque fold.

Saige Walton is Lecturer in Screen Studies at the University of South Australia. Her first scholarly monograph, Cinema’s Baroque Flesh: Film, Phenomenology and the Art of Entanglement, is forthcoming from Amsterdam University Press and the University of Chicago Press (Fall 2016).

Notes

[1] David Ehrlich, “Director’s Cut: Claire Denis (‘Bastards’).” Film.com, October 11, 2013, accessed 21 February 2016. http://www.film.com/movies/claire-denis-interview-bastards-directors-cut.

[2] For Bruno, the fold can help “bridge the gap” between Deleuze’s concepts of the movement-image and the time-image because it “holds the potential to incorporate the flow and texture of temporality in the unreeling of inner space”. See Giuliana Bruno, Surface: Matters of Aesthetics, Materiality and Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 16.

[3] In an interview with Cahiers du Cinema, Denis describes the ending as “an almost baroque image”. See Nikolaj Lübecker, The Feel Bad Film (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2015), 141.

[4] Deleuze, The Fold, 159, f.n.32.

[5] According to Denis, her lead needed to be “a strong, dependable man like Toshiro Mifune” in Kurosawa’s film who could function in the roles of both victim and hero. Bastards Press Kit, Wild Bunch, 7 August 2013, n.p.

[6] Douglas Morrey, “Introduction: Claire Denis and Jean-Luc Nancy”, Film-Philosophy 12, no. 1 (April 2008), iv.

[7] Rosalind Galt, “Claire Denis’s Capitalist Bastards”, Studies in French Cinema 15, no. 3 (2015), 277.

[8] Cathryn Vasseleu, Textures of Light: Vision and Touch in Irigaray, Levinas and Merleau-Ponty (London: Routledge, 1998), 3.

[9] Galt, 284.

[10] Jose Teodoro, “No Sanctuary: Claire Denis on Bastards”, Cinema Scope, accessed 27 February 2016, http://cinema-scope.com/cinema-scope-online/sanctuary-claire-denis-bastards/. Denis has been very emphatic about portraying Justine as “walking tall” in shoes during this sequence rather than appearing barefoot. See Ehrlich, n.p.

[11] See Ehrlich as an example.

[12] Lübecker, 135.

[13] Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (London: Continuum, 2005), 50.

[14] Deleuze, Cinema 1, 50.

[15] Bastards Press Kit, n.p.

[16] Bastards Press Kit, n.p.

[17] Deleuze, Fold, 31.

[18] Deleuze, Fold, 31.

[19] Deleuze, Fold, 31. The use of a tinted background (gesso) predates the historical baroque age, though we can agree with Deleuze that baroque artists used it to their own ends in privileging effects of shading and dark light.

[20] Deleuze, Fold, 32.

[21] Deleuze, Fold, 31–32; italics mine.

[22] Deleuze, Fold, 32.

[23] Deleuze writes that the “Baroque has no reason for existing without a concept that forms this reason”. See Deleuze, Fold, 33; italics mine.

[24] Deleuze, Fold, 3.

[25] Deleuze, Fold, 34. Deleuze himself references the French filmmaker Jean Cocteau with regard to the fold. See Fold, 155, f.n. 20.

[26] Lübecker, 137.

[27] Lübecker, 137.

[28] Deleuze, Fold, 32.

[29] Deleuze, Cinema 1, 121.

[30] Deleuze, Cinema 1, 121; italics mine.

[31] Deleuze, Cinema 1, 121.

[32] This is Galt’s reading of the film, although the identification of the other woman in the tape is visually ambiguous. Regardless of whether she did or did not participate in the scene, it is made clear to Marco prior to his death that Sandra was complicit in prostituting her daughter.

[33] Christine Buci-Glucksmann, The Madness of Vision: On Baroque Aesthetics, trans. Dorothy Z. Baker (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2013), 40.

[34] Buci-Glucksmann, 45.

[35] Buci-Glucksmann, 45.

[36] Buci-Glucksmann, 45.

[37] Buci-Glucksmann, 45.

[38] Deleuze, Fold, 33.

[39] Deleuze, Fold, 33.

[40] Deleuze, Fold, 3–4.

[41] Deleuze, Fold, 5.

[42] Deleuze, Fold, 29.

[43] Galt, 287.

[44] Here, I am thinking of the more nihilistic endings of mid-to-late fifties noir films including Kiss Me Deadly, The Sweet Smell of Success (Alexander Mackendrick, 1957) and Touch of Evil (Orson Welles, 1958). On the genre reworkings and corporeal extremes of contemporary French cinema see Martine Beugnet, Cinema and Sensation: French Film and the Art of Transgression (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2007).

[45] Patricia McCormack, Cine-Sexuality (Hampshire and Burlington: Ashgate, 2008), 78.

[46] McCormack, 73.

[47] Deleuze, Fold, 35.

[48] Deleuze, Fold, 32. There are definite formal parallels between Deleuze’s evocative description of the free-flowing baroque fold and the “pure optical and sound situations” of the time-image with their “liberated sense organs” and loosening of the sensory-motor schema. See Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (London: Continuum, 2005), 1–3.

[49] John Rupert Martin, Baroque (London: A. Lane, 2007).

[50] Bruno, Surface, 20.

[51] Bruno, Surface, 5.

[52] Deleuze, Fold, 115.

[53] Deleuze, Fold, 115.

[54] Deleuze, Fold, 159, f.n.32.

[55] Deleuze, Fold, 30. As McCormack points out, Deleuze’s discussion of baroque art links light with life and benevolence and darkness with malevolence and death. See McCormack, 85–86.

[56] Deleuze, Fold, 30–31.

[57] Buci-Glucksmann, 45.

[58] Ehrlich, n.p.

[59] Denis describes this scene as involving the characters “flying with the car and switching off their light, they are in the flow of life […] it’s important to show the wrecked car, because it is as if their bodies were torn […] it was more effective than a lot of blood and wounded people. It says more”. See Ehrlich, n.p.

[60] Elena del Río, Deleuze and the Cinemas of Performance: Powers of Affection (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2008), 169.

[61] Ehlrich, n.p.

[62] Denis’s frequent collaborator Stuart Staples composed the electronic version of the song. Denis had wanted an overtly electronic and synthetic-sounding score for the scene along the lines of Tangerine Dream’s scoring for Michael Mann’s Thief (1981). Bastards Press Kit, n.p.

[63] Bastards Press Kit, n.p.

[64] McCormack, 87.

[65] Lübecker, 143.

[66] Deleuze, Cinema 2, 164.

[67] Bastards Press Kit, n.p.

[68] Deleuze, Fold, 35.

[69] Deleuze, Fold, 35.