The Huge Listening Contraption

Neil Verma

Link to film clip in criticalcommons.org: “’Listeningness’ in HANGMEN ALSO DIE”

Fig 1: Gene Lockhart as Nazi Mole Emile Czaka in Fritz Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

This essay argues for an approach to mapping films based on what Michel Chion calls their “systems of audition”: patterns of who can hear and who can be heard – by whom, where, and when in the world of the fiction. [1] I focus on a film that I’ll argue is preoccupied with circulations of voice across tight spaces of audition and misaudition, but one that has never really been read that way, Fritz Lang’s 1943 thriller Hangmen Also Die. [2] In pursuing this approach, I’m trying to account for one fascination of Hangmen – a texture of “listeningness” throughout the dramaturgy – that is common among wartime films (which frequently explore listening devices and eavesdropping sequences, a cinema of eyes well-aware of ears everywhere), yet is also hard to pinpoint. To do so, what follows shifts the film from the fraught archaeology of its creation, which has consumed scholarly study for decades, and reimagines it as a political allegory of the feeling that someone is listening in a miniature golden age of cinematic engagement with that topic. [3]

Lang famously began working on the thriller after a visit he paid to the exiled playwright Bertolt Brecht on May 28th, 1942. On that occasion, the two took a walk on the beach and discussed the assassination of Nazi leader Reinhard Heydrich. An architect of the Final Solution, Heydrich was known throughout Europe as “the hangman” and “the man with the iron heart.” In an RAF-backed operation code-named Anthropoid, commandos Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš had cornered his Mercedes near Bulovka Hospital at 10:30 am on May 27, but fled after a gun jammed and a grenade was misthrown.

Fig 2: An image of Nazi grandee Reinhard Heydrich at the Lidice Memorial. Photo by Adam Jones, used with Creative Commons license.

Heydrich survived, then died mysteriously seven days later, perhaps due to a blood infection stemming from the car’s upholstery forced into his body by shrapnel. Vengeful Nazis massacred hundreds of civilians as a reprisal, an infamous event that became the basis for Edna St. Vincent Millay’s ballad “The Murder of Lidice,” as well as two other 1943 films, Douglas Sirk’s Hitler’s Madmen and Frank Tuttle’s Hostages. [4] Lang and Brecht’s own film idea was fleshed out over two days in May after which they registered a 39-page outline with the Screen Writer’s Guild. By mid-July Brecht had dictated a 95-page typescript entitled Never Surrender!, which was translated by UCLA student Hans Viertel. [5] Soon Brecht and Lang teamed with producer Arnold Pressburger, writer John Wexley, composer Hanns Eisler and cinematographer James Wong Howe to produce the film for United Artists, even as the budding artistic friendship at the core of the project had begun to wither, ending in ugly clashes over money, casting and credit. After a hearing stripped Brecht of primary credit in 1943, he never saw Lang again.

Hangmen begins with the death of Reichsprotektor Heydrich in Prague. The assassin, Dr. Svoboda (Brian Donlevy), learns that his getaway is compromised and seeks the aid of bystander Mascha (Anna Lee). As Svoboda takes refuge in the home of Mascha’s father, Professor Novotny (Walter Brennan), Gestapo commanders round up suspects and terrorize the occupied city, using radio to publicize their massacres aimed at convincing citizens to turn the assassin in. Svoboda and Mascha dodge suspicion, staging deceptions that require her to seem to betray her fiancée and family, a “mystery in reverse” in which the antipathy we feel toward a murderer is transmuted into sympathy, as Erhard Bahr has pointed out. [6] Meanwhile, Professor Novotny and his countrymen are imprisoned, coping with their fate philosophically as they are killed at intervals by relentless Nazis (Brecht envisioned this as a stand-alone Lehrstück about German brutality to show after the war). Meanwhile, police investigator Alois Gruber (Alexander Granach) tracks down the real killer. One last sequence of events centers on the resistance, which is in the midst of its own investigation, in the belief that a mole is undermining them from within. Hangmen thus doubles the most Langian of narrative pretexts – the manhunt – and fulfills Brecht’s wish to see the oppressive hierarchy of the Nazis mirrored in that of the rebels. The mole, petty bourgeois brewer Emile Czaka (Gene Lockhart), is scapegoated for the Heydrich attack by a conspiracy of citizens lying about his involvement. Only Gruber uncovers the true culprit, but he is killed in a harrowing confrontation with underground orderlies at St. Pankrác hospital. Finally, Czaka is hauled before the SS and shot in the dark before a church. Later, the Nazis realize his innocence, but quash the report to save face, and the film concludes with German retribution claiming the lives of Novotny’s group, and the defiant song of the prisoners under a title “Not the End.”

Scholarship on Hangmen has long wrestled with the vexing task of ascertaining the “real” authorship of various elements of the scenario, from the glorification of a lie that implicates Czaka to the vocal translation sequences and the triple-plot structure. [7] In this encounter between film noir and epic theater, the question goes, who is responsible for what, and which aesthetic carries the day? At the moment, the question hinges on the rediscovery of the Brecht typescript by Irène Bonnaud in 1997, a document that seems to contain some 90% of plot elements, according to an estimate by James Lyon. Wherever they stand on that matter, most writers also evince disappointment with the film itself. Walter Metz put it this way:

Hangmen Also Die is, on paper, the most important film ever made concerning cinema and modernity, with a highly allegorical filmmaker in charge of a script by the most important modernist playwright. And yet, for whatever reason, Hangmen Also Die is an astonishingly conventional film. [8]

I would argue that not only is this mood of woe unproductive, but Hangmen is no longer well served by holding it hostage to critical investment in the aesthetic regimes of the personnel behind it. To start again with Hangmen, I propose another kind of origin in the scene with Lang and Brecht on the beach, one focusing not on the auteurs strolling across the sand, but their surroundings. Here is Brecht’s journal entry about the encounter:

With Lang, on the beach. Thought about a hostage film (prompted by Heydrich’s execution in Prague) there were two young people lying close together beside us under a big bath towel, the man on top of the woman at one point, with a child playing alongside. Not far away stands a huge iron listening contraption with colossal wings which turns in an arc; a soldier sits behind it on a tractor seat, in shirtsleeves, but in front of one or two little buildings there is a sentry with a gun in full kit. Huge petrol tankers glide silently down the asphalt coast road, and you can hear heavy gunfire beyond the bay. [9]

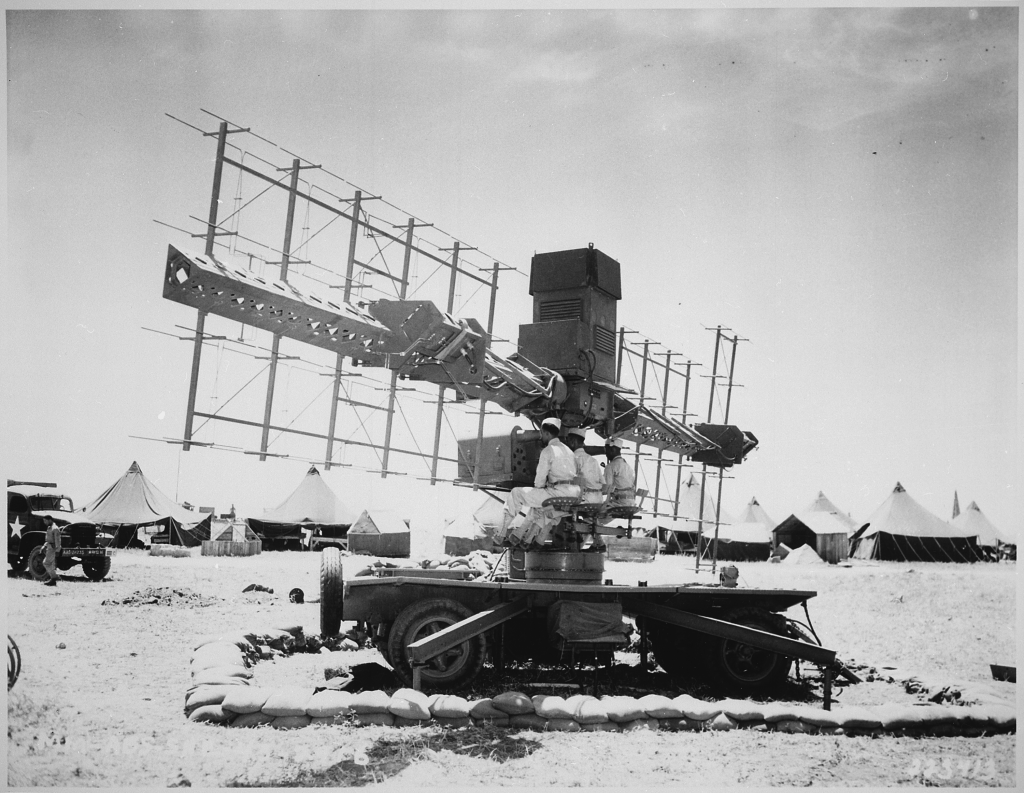

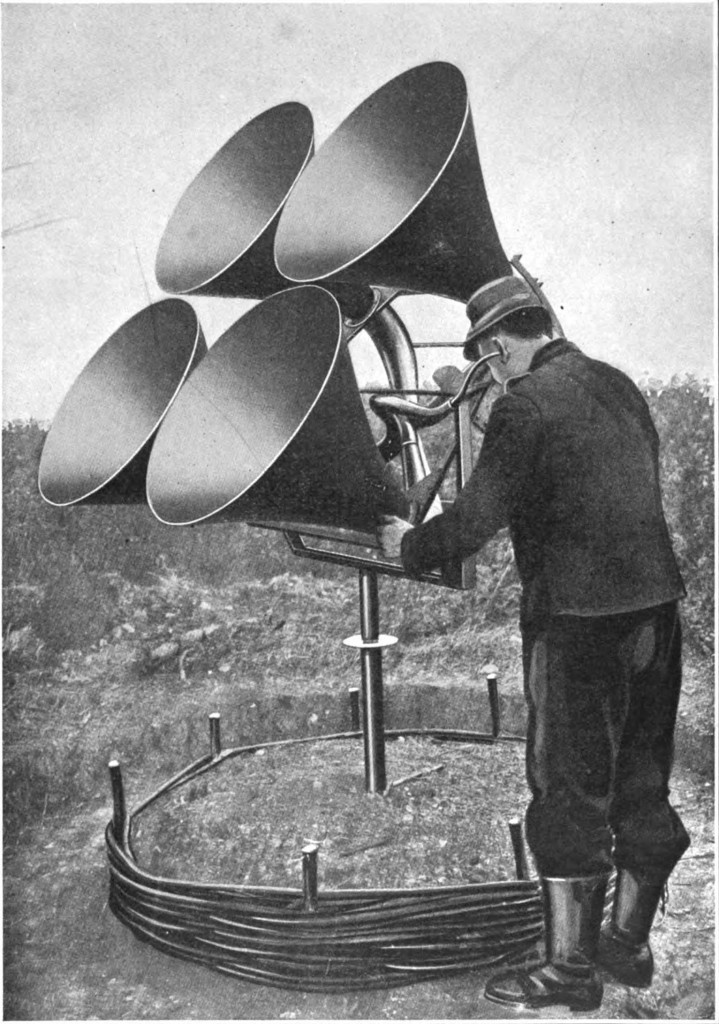

Among his rich observations of American dress and manners, Brecht’s sonic sensitivities are striking, as the scene is haunted by drilling warships and gliding silent tankers. And what could that “huge iron listening contraption” have been, I wonder? Lang biographer Lotte Eisner reckons that the setting is the bay at Santa Monica, where Brecht was then living at 817 25th Street, the first of two houses he shared with his wife Helene Weigel. If that is the case, and if his description of the colossal wings is right, then it might have been an SCR-268 radar installation, one in an early generation of mobile radar communications devices deployed along the coast that spring to guard against surprise attack from Japan.

Of course Brecht is wrong about how radar works. It emits inaudible pulses and measures their reflection off distant surfaces. He probably looked at a radar and thought he saw one of the many acoustic listening devices used by military forces across Europe to catch the sound of oncoming planes since the Great War.

According to Brecht’s understanding, in other words, he and Lang were surrounded by a hulking eavesdropping machine, before whose prodigious earshot the landscape seemed entirely subjugated.

Or was it? Just two months prior to Brecht and Lang’s walk on the beach, the coastal defense system had been embarrassed by the so-called “Battle of Los Angeles.” On the night of February 24, 1942, following shelling by Japanese submarines near Santa Barbara, a stray weather balloon set of a series of radar alerts, air raid sirens and a mandatory blackout across L.A. Jumpy antiaircraft gunners fell victim to their own nerves, firing thousands of rounds up into the air at phantom Japanese bombers, resulting in destroyed cars and property, as spent shells plummeted back to earth, in one of the most prominent false alarms in a season of many.

That lesson about a vast system of audition that is powerful and yet vulnerable to its own power is a hint that we might follow into the dramaturgy of Hangmen, a film that has disappointed critics, I argue, precisely because their quest for an allegory about the politics of vision turns up one about hearing. This is apparent from the earliest moments, as we open on a larger-than-life painting of Hitler gazing down into Prague castle over ten Nazi flags with trucks of golden eagles. Lang’s camera dissolves to see some thirty officials congregating, Czech bureaucrats in garish ties and petulant German officers under a clatter of medals and beltwork, who debate the unrest at the nearby plant at Skoda, where rebels have spread propaganda. Heydrich enters as a venomous monster, a fitting leader for the obese, syphilitic and drunken Germans populating the film – small wonder that Hangmen was received by the public as ruthless, violent and grotesque, as Sheri Chinen Beisen has observed. [10] In Heydrich’s case it’s all in the voice. Leaning against the desk, he growls a series of spittle-ridden orders evincing a maniac need to command all listening, smiling and gesturing to his timid translator: “The reports from Skoda are a putrid mess. The stinking swines at Skoda refuse to work…” But soon his translator can’t keep up. Heydrich barks at one Czech whispering to another within hearing. When a third local has the temerity to speak up, he is admonished for failing to speak the new tongue of the realm. “Deutsch, Deutsch, Deutsch, Deutsch!” rants Heydrich, pounding on the table. Half the room stands confused, waiting, just like most of the American audience in 1943. In this way, the film institutes and dramatizes a delay of meaning in a single gesture, asserting an empire of voice while circumscribing a zone of understanding within that space, attempting to structure the auditory systems of the world of the film by sheer vehemence.

The mood transforms in the next scene. Cheerful Mascha Novotny crosses a busy square in search of potatoes from a kindly shopkeeper as children scamper through still pools of old rain. Brian Donlevy appears playing assassin Svoboda, running through jagged streets toward the intersection. Changing hats, he ducks into a doorway. The next image is the most famous in Hangmen, vivid proof of why Lang considered himself lucky to hire cinematographer Howe, so adept at making a single shot do the work of two. On the left, a deep space populated with active, boisterous enemy bodies, turning to and fro in a bright kinetic world. On the right, a shallow enclosed space with a body stock-still in the gloom. On the left, soldiers and oppression. On the right, civilians and resistance. On the left, a cascade of eyes. On the right, an ear just catching the light. This picture of the visual rhetoric of listening – active, engaged listening – signals a complex relation with listening devices, and with listening as a device sustained through the film, in which Czechs may live in an environment thick with the hearing of alien occupiers, but far from being undone by this stifling situation, they weaponize it. Unable to control their own audibility – the sense of one’s relative availability for listening by an ear out there beyond sight – life in Prague becomes a perpetual drama performed for a variety of searching ears.

Fig 5: Brian Donlevy as Dr. Svoboda, here pictured not looking out for his pursuers, but listening for them beyond the wall.

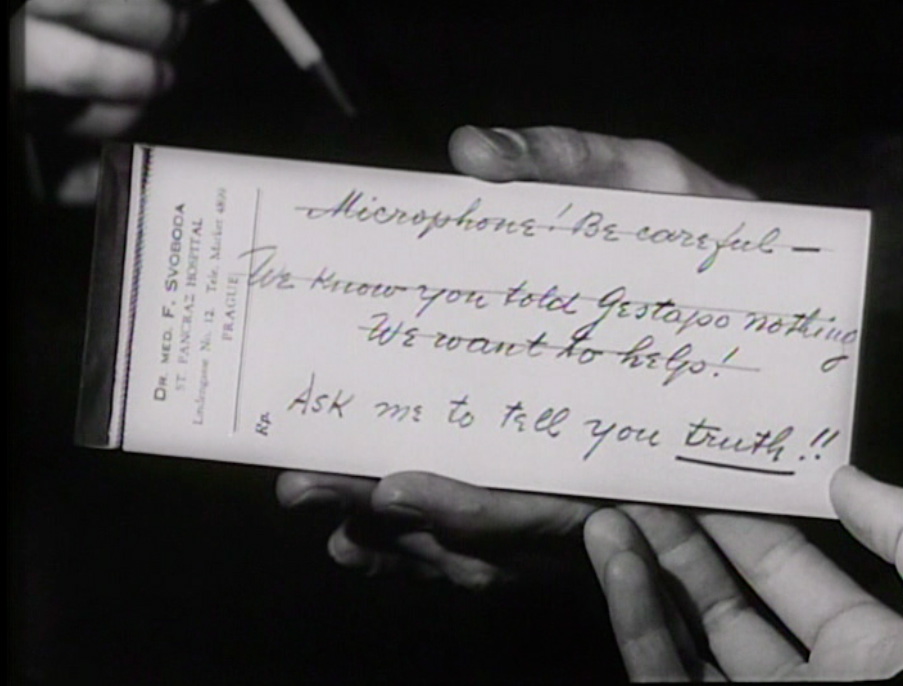

The scene featured in the clip at the beginning of this article captures the situation, a luncheon among rebels in which a waiter tells a gag about Hitler and Goebbels keeping the little food left in Germany for themselves and away from portly Herman Göring (a “Flüsterwitze” joke possibly included by Brecht himself) during which Czaka reveals that he understands German, despite an oath to the contrary. [11] In Hangmen, it seems, both knowing German and not knowing German can produce parallel dangers. The scene is theater within theater: like Czaka, the camera is invited to the table through a lowering menu and a crisscross of bodies like a curtain parting for a play beyond a proscenium arch. Czaka sits across the table from the purported audience of the joke “on stage,” tempted to look while within earshot of a burlesque designed so that he cannot help but listen and picture its content, inevitably vocalizing with a “tell.” It is surely a trap, but not quite a trap for the “mind and the eye” as Thomas Elsaesser might characterize it – more like a trap for the eye of the mind. [12] We watch the rebel leader observe signs of awareness cross Czaka’s face, then finally hear his unrestrained laughter emerge off-screen, seemingly bursting from inside the false and fading laughter of the three performers in front of him. In exhibiting listening, Czaka is revealed to be the object of listening and the listener-in-hiding all at once. When the camera cuts back to the unmasked Quisling, he is swaying with laughter that abruptly dies, replaced with the silent stares of his companions in a highly paranoid vortex of eyes seen in POV. The “actors” on the far end of the table now accuse the “actor” on the near end. In this way, the Langian device of the unguarded moment produces an accusatory and dialectical breakage of a “fourth wall,” perhaps the one shot of the film in which the best-known elements of the aesthetics of Lang and Brecht interlock seamlessly.

Clearly, the rebels are manipulating their own audibility to fool the “iron contraption” that the ear of power has built around them. Indeed, on no less than five occasions, the film stages scenes similar to the luncheon, in which a character is shown behind an object that removes visual faculty as they hear an audio play performed for their benefit by canny rebels. A memorable instance occurs when heroes Dr. Svoboda and Mascha pass notes to one another “scripting” lover’s dialogue in real time for Gestapo inspector Gruber on the other end of audio surveillance equipment, as if listening to a soap opera.

Another occurs toward the end of the film, when Svoboda and Mascha are hiding a leader of the underground in the apartment and see Gruber’s shadow on the other side of the door after he has seemingly left the scene. The two hastily improvise a phony quarrel to mislead the investigation.

Fig 9: Listening in on the underground meeting to ascertain who else might be listening in on the meeting.

In all of these cases, awareness of one’s place within earshot is a potent weapon: what Tom Gunning has called the rebellion’s “stage management of reality” is actually the sound management of reality. [13]

The last of the five “sound plays” in Hangmen takes place again with Czaka as target of counterconspiracy – as Nick Smedley has explained, in dramatic terms Czaka’s self-serving collaborationism is but a foil for aggrandizing collective action against him. [14] Mascha stages an argument in front of the Nazi thugs suggesting that Czaka was the assassin.

Czaka rightly calls it “making a scene.” Their words gradually become audible to both Gestapo eavesdroppers and the film audience, with fatal results (the Hays office objected to this, since it glorified a lie, but Lang fought to keep it in). Laughing uncontrollably at reality shifting around him, Czaka is driven to his execution. The last thing he hears before he is killed by Nazi soldiers is their acousmatic laughter, in the dark. “He who laughs last” goes the Brecht quote “has not yet heard the bad news.” [15] Czaka is reduced to a performance from which he never escapes, shot within earshot. As Jean-Louis Comolli and Francois Géré once wrote, “It is when Czaka no longer matters to anybody in the fiction that he begins to matter to us.” [16] And why shouldn’t he? A long-hidden eavesdropper who becomes acoustically naked and caught up in the contraption of his own listening, Czaka is snared by the system of audition that the film has so carefully laid out, and Hangmen also Die arrives at its killing joke.

Neil Verma is a visiting assistant professor in Radio/Television/Film at Northwestern University. Verma is the author of Theater of the Mind: Imagination, Aesthetics and American Radio Drama (University of Chicago Press, 2012), which won the Best First Book Award from the Society for Cinema & Media Studies. He has recent and forthcoming articles in The Journal of American Studies, RadioDoc Review, The Journal of Sonic Studies, Critical Quarterly, and The Velvet Light Trap, and is co-editor (with Jacob Smith) of Anatomy of Sound: Norman Corwin and Media Authorship, forthcoming from the University of California Press.

Notes

[1] Michel Chion, Film, A Sound Art, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 492-93.

[2] I presented this paper in Madison at the Film & History conference in 2014. Thanks to Eric Dienstfrey and Katie Quanz for their invitation, as well as to David Bordwell and Tom Gunning for their comments.

[3] See Neil Verma “Film Noir and the Aesthetics of Acoustic Spectacle,” in Kiss the Blood of My Hands: Re-Screening Classic Film Noir, ed. Robert Miklitsch (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014), 80-99.

[4] See Robert Gerwath, Hitler’s Hangman: The Life of Heydrich (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012).

[5] James K. Lyon, “Hangmen Also Die Once Again–Dispelling the Last Doubts About Brecht’s Role as Author,” The Brecht Yearbook 30, 1-6.

[6] Ehrhard Bahr, Weimar on the Pacific: German Exile Culture in Los Angeles and the Crisis of Modernism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 143.

[7] See, e.g.: Bahr, as well as Lotte Eisner, Fritz Lang (Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd, 1976); James Lyon, Bertolt Brecht in America (Princeton, 1980); Patrick McGilligan, Fritz Lang: the Nature of the Beast (St. Martins, 1998) and Larissa Schütze, Fritz Lang im Exil: Filmkunst Im Schatten Der Politik (Peter Lang, 2006).

[8] Walter Metz, “Modernity and the Crisis in Truth: Alfred Hitchcock and Fritz Lang” in Cinema and Modernity, ed. Murray Pomerance (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006), 74- 89.

[9] Bertolt Brecht, Journals 1934-1955, John Willett and Hugh Rorrison, eds. (New York: Routledge, 1993), 235.

[10] Sheri Chinen Beisen, Blackout: World War II and the Origins of Film Noir (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), 70-71.

[11] Hans Teuchert, “Bertolt Brecht’s Contributions to the Screenplay of ‘Hangmen Also Die’” Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of California, San Diego (1980), 86.

[12] Thomas Elsaesser, Weimar Cinema and After: Germany’s Historical Imaginary (London: Routledge, 2000),186.

[13] Tom Gunning, The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity (BFI, 2000), 295.

[14] Nick Smedley, A Divided World: Hollywood, Cinema and Émigré Directors in the Era of Roosevelt and Hitler, 1933-1948 (Intellect, 2011), 231-32.

[15] Bertolt Brecht, “To Those Born Later” Poems 1913-1956 (New York: Routledge 1979), 318.

[16] Jean-Louis Comolli and Francois Géré “Two Fictions Concerning Hate” in Fritz Lang: the Image and the Look, ed. Stephen Jenkins (London: BFI, 1981), 146.