The Act and the Actor

Jacques Rivette

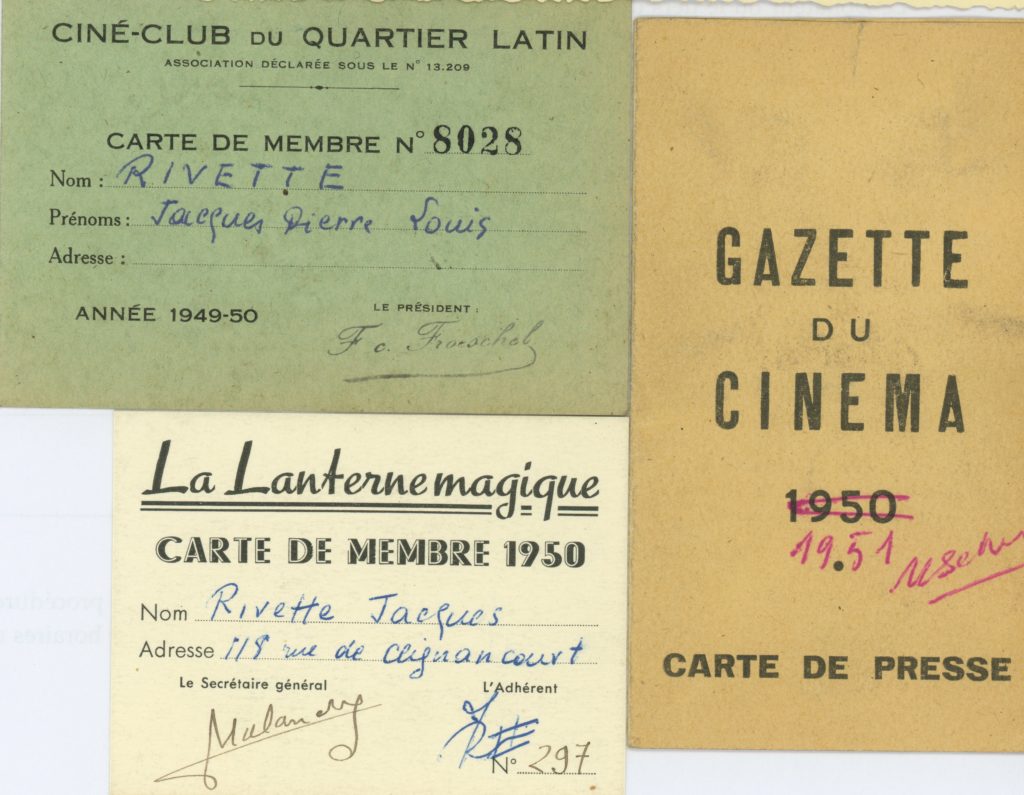

“The Act and the Actor” was discovered among the loose-leaf pages of a musty old notebook, which likely had not been opened in over fifty years. Rivette had drafted the text between the writing of two articles, “Nous ne sommes plus innocents” (January 1950), which appeared in Le Bulletin intérieur du ciné-club du Quartier Latin, and “Under Capricorn d’Alfred Hitchcock” (October 1950), which was published in La Gazette du cinéma. In the unedited text that appears here, the twenty-two-year-old filmmaker offers a pensive reflection upon the importance of the role of the actor, which closes with an incisive articulation of the interrelation of film and theater. There remains the unanswerable question of why he ultimately refrained from publishing this important piece, which, perhaps even more than his other early essays, hones in precisely on those very aesthetic issues that were closest to his heart and destined to become central in the evolution of the oeuvre. Therein lies a quintessential Rivettian mystery.

—Mary Wiles, editor, with the assistance of Véronique Manniez-Rivette

Gaston Bachelard defined the poetry of Lautréamont as a poetry of human dynamism: motor impulses and muscular excitations, which sustain and create the body. Metamorphosis, a play of formal connections, is only the appearance of the succession of impulses that Lautréamont wanted to see emerge in his reader, in inverse direction: from the organs to their functioning, from metamorphosis to muscle.

We need to think gesture: the free and gratuitous play of impulses without the necessity of corporeal actualization: an entirely mental dynamic, a psychic gymnastics, where man panders to the imagination of movement, more simply to its representation, stripped of all bodily limitations or constraints; the intoxicating power of the spirit on movement freed of all materiality makes it master of unlimited dynamism. To think gesture: such is the privilege of the spectator, as much as for the reader of Lautréamont’s Maldoror.

The dynamic imagination is a fundamental component of the human mind; it is ceaselessly moved by passing appearances. Man is a center of impulses, which are almost always inhibited; he is perpetually reacting to perceptions. The inert or the moving object can lay equal claim to his reactive gestures.

One impulse is intervention: with an animal, one catches, strokes or strikes it; with an object, one grasps. (Education and habit could not entirely suppress the fundamental desire to touch what appears before our eyes: to see an object is to think about seizing it, weighing it up, measuring its tactility. And sometimes, having lost control of ourselves, our impulses, brusquely ceasing to be inhibited, can burst—so that we actually throw the object or break it).

A different impulse is imitation: here we identify with our likeness, our “neighbor.”

The notion of the other is introduced through hostility or desire; we refuse identification, opting for brutal rejection or for capture.

In this way, the infirm is dehumanized by his infirmity; the kick in the belly of the blind man gratifies a profound impulse; after which he, due to his singular presence beneath our gaze, compels us to identify with his infirmity. A violent response follows, which pushes the perpetrator away into an inhuman universe of objects, affirms our autonomy, our refusal of participation, and “frees” us from an unpleasant internal prison. This explains why people hiss the “villain” in westerns.

I

To watch man act is to oneself inwardly imitate his act. Whereas one is freed only through laughter—refusal of participation—from the painful sensation of watching a bungled act, the pleasure that is provided by a smooth gait or a specific dance explains the attraction of ballet performances and athletic competitions. Thus, when people emerge from cinemas, their comportment varies in response to that of the star of the film.

For the cinema is the first art that reproduces movement and, better even than dance, makes it the very substance of its modus operandi and its raison d’être. Psychical imitation is just as concerned with the recording of movement.

The mechanism of the spectator’s identification with the actor is not so much psychological as dynamic.

The necessity of heroes is born from the difficulty that coarse minds have in following diverse elements simultaneously (like reading subtitles). If the vision of an anarchic and disorganized crowd leaves the spectator feeling overtaken, overwhelmed by the number and the confusion, unable to pick out a significant individual, or discern certain lines of force, this will oblige the spectator to escape this agonizing struggle, to “disengage,” and leave the cinema. But when he sees an organized crowd, the intoxicating feeling of participating alongside a thousand bodies gathered together provides him with the illusion of a heightened existence, by simple multiplication (sports parades, military exercises). The experience of identifying simultaneously with diverse actors and of following the polyphony of their behavior offers a more refined pleasure.

I

It is by way of the actor—and through him—that the spectator is primordially affected; and not the actor-character, with his specific mode of thought and mental universe, but the actor-subject of acts, nodal point of gestures. Through his participation in certain corporeal acts, the spectator merges with and is incorporated into the actor (and can thus, in a roundabout way, unconsciously imitate his successive psychological operations, to the extent that his acts depend on them).

Each role is thus determined, not by some psychological unity, but by a continuity of conduct, and a close similarity of gesture that is obtained while performing and always following the same angle to achieve the deformation necessary—for a style of the act.

I

It is a question of imposing such acts on the spectator. Verbal lines, spoken words are acts to the same degree as gestures—not fragments of witty, anonymous conversation, or the shorthand of prosaic speech—subjected, as are gestures, to transposition to the screen. Speaking offers the possibility of a total subjugation of the spectator, who appears intimidated. This explains this persistent search for the “natural” and the anodyne. The spectator has a fear of the realism of sound on the screen, for the realism of reproduction bestows a heavily concrete existence on the talking “monsters,” screen idols, whom the silent cinema had isolated behind a glass aquarium— which is now shattered forever. He refuses to relinquish his liberty other than to inoffensive doubles of himself, who are like his neighbors, or to feuilletonesque ideals (which are only the mythic projection of mediocre potentialities); or else he demands tamed and castrated wildcats, whose company is thereby “possible.” Faced with the monster on the screen, who tries with impertinence to impose his superior deformities, the spectator cannot seal his refusal of identification with a slap in the face and has no other resources for reconquering his poor self than to laugh or to become angry.

We must dream of a cineaste who would dare to submit the spectator both to sonorous realism, and the ample rigor of mute gesture.

I

The cinema is an art of movement. It can be concerned with the motionless only as accidental and ephemeral, such as human immobility, which is only ever a moment of the movement, an act. Natural movement (water, trees) only offers to the eye a passing distraction; movements that are always identical, and similarly oriented. The difficulty of identification, the near impossibility of “direction”—thus of an expression belonging to the creator’s vision—limits animal subject-matter, in spite of its greater freedom, to random successes, a naïve, yet instinctive poetry, organized according to natural behaviors, these being also uni-oriented.

Only the actor, besides having the greatest possibilities of identification, possesses the malleability necessary for certain expression: he elevates movement to the dignity of gesture. Drawings and animated dolls, which are limited by their unreality, can actually produce a dynamic impact—given that identification can occur only for a brief time—but that is exceptionally intense by virtue of their freedom. The laws of identification vary according to individual minds. Certain psyches absolutely refuse purely dynamic identification; others require an actor with certain characteristics and will not identify unless he or she has a particular size, sex, or hairstyle—we can, however, suggest a general rule, the necessity of the “human creature.”

To record acts, which are minimally decomposed and fragmented by the mechanical process; to fix an objective look on the protagonist. Every film is a documentary about the actor.

Only through the actor can the creator express himself, and reach the spectator; how do certain cineastes reject the temptation to act, themselves? Everything must be subordinate to the actor and in fact, “like it or not,” does depend on him. Everything has to be a way of reaching the actor, from the camera movements, which follow him, to the décor, which reflects him.

I

In this universe, natural and artificial décors have no other use than to counterpoint man: they are a basso continuo having value only through the song of human gesture, which governs on a human scale the world of appearances, orients it, and gives it sense. An empty décor calls for man, imposing the feeling of an intolerable void, which is “against nature” and never experienced in everyday life—where the I that is always present can only ever feel a sense of solitude; the spectator who does not know who or what to hang onto and identify with is irretrievably rejected from an inhuman universe.

The universe only has cinematic value in the certain view of its rapport with man who confronts it and is part of it. Everything must be experienced and passed through him; nothing is valued other than what is experienced—and resonating—through his contact with it.

Far from submitting the actor to a few or many “components” of the film, everything must be ordered according to him, from him, since he gives everything its raison d’être. The actor should be subject only to the creator, who makes him his first—and in a certain way, unique—objective; who shapes him, models him, creates him, according to his design, and will thereafter endeavor only to release the “beast” into his universe (fashioned in his image, to serve him, by requiring him to act). The essential resides in this recreation of the creature, from gross human clay, in this modeling of the carnal puppet, in the “torturing” of the actor. This prompts one question: what might the beast be like (the beast of the cinema, as one speaks of the beast of the theatre?)

It is, in its extreme form, mythification: the star, the actress (or the actor) destroying everything around her, alone, monopolizing all attention; the camera can no longer detach itself from her. Everything around her is erased and dissolves into non-being. She reigns alone in a universe where she represents everything. Alone and immobile.

Here cinema accomplishes, achieves, and destroys itself. An idol that is immobile and thus dead, by an excess of existence.

There is movement—antagonism or sympathy—only in relation to something else. In order for the gesture to become an act, the actor has to be inserted.

The actor considered as a machine of gestures; not man, but “dummy”: a superior puppet, a motorized center, a subject of acts. A film is a fabric of acts where psychology (sociology, metaphysics…) only ever occupies a parasitic place. Only the “film of actions” exists: made from concrete evidence, whose beauty and efficiency alone concern us, and about which all explanation would refer only to an order of ulterior values, which here are absurd and incomprehensible. A tissue of acts, and the act exists through the actor who incarnates it, realizes it, and dissolves it (the actor destroys through the act): act and actor merge within the same reality, the actor being no more than the appearance of the act, its concrete manifestation; the act being no more than the actor’s natural rhythm, his breathing, his vital milieu, and his mode of existence; the actor existing only through the act, the act only by means of the actor.

I

The movement, the gesture, the act: these are thus the elements that the cineaste uses; he must play with the actor as his only means of expression.

The creator imposes a gesture on the actor, which is imposed on the spectator; there is thus direct, immediate action, which attains a physical presence through the psychological, at an extreme point of being where the spirit and the body are conjoined and are merged. Intimate modeling of the spectator by the creator through the actor. The cineaste, a creator of gestures, must force the spectators to accomplish acts to which they are unaccustomed. The human body is his material. It is always malleable and ready for new expressions and an infinite variety of nuances. The gesture, always new, never identical to itself, even in the most demanding rehearsal, presents itself in the moment, always virginal and fleeting, and like cinema, a perpetual improvisation.

We need a poetics—a poϊétique—of the human gesture. To use the pure gesture, as one does “the pure word” in poetry. “To yield the initiative” to acts.

All this could be equally said of the theatre; which is to say, essentially nothing opposes, or even separates these two means of expression; both are the realization of an “active” universe; the actor incarnates and objectifies a dramatic moment; “something” happens that must above all be shown and presented; be it the stage or the screen, the curtain or the trestle, there is nothing more to do than to see.

Translated by Mary Wiles and Peter Low

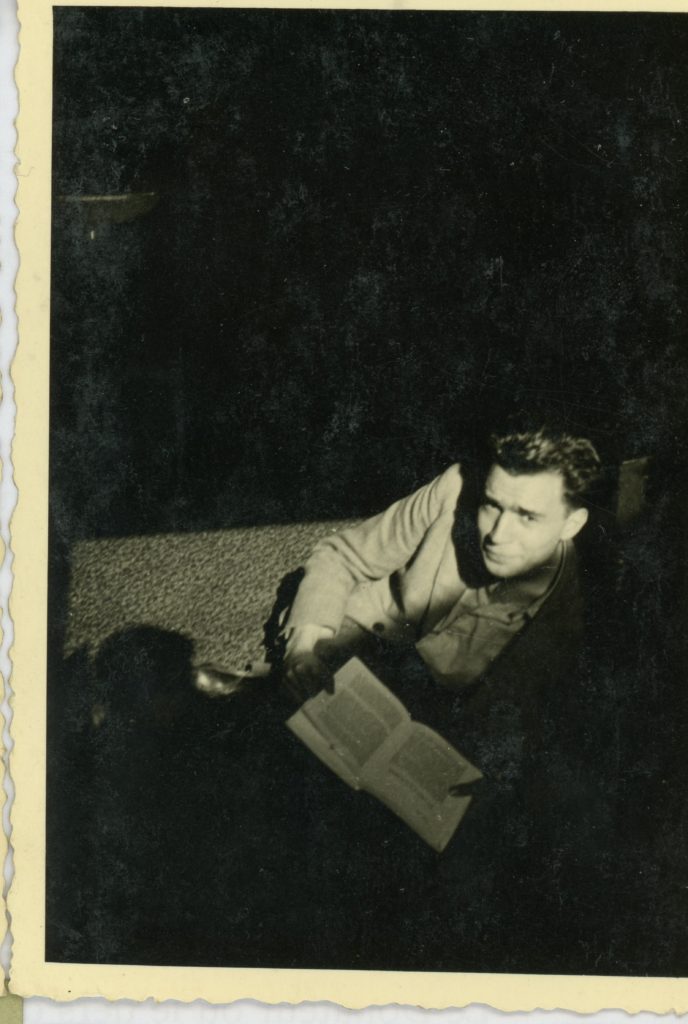

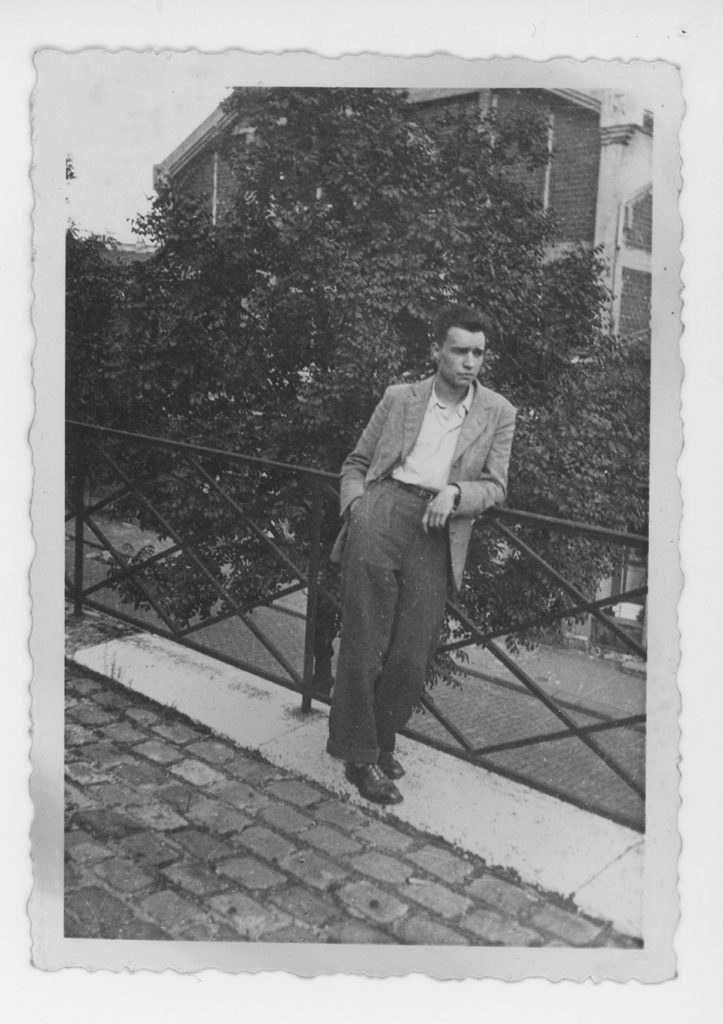

We would like to express our gratitude to Véronique Manniez-Rivette for sharing this previously unpublished essay, “The Act and the Actor,” with us and also for permitting us to enjoy these touching photographs from her personal collection.

______________________________

The French text, “L’acte et l’acteur,” will be published in the forthcoming 121/spring-summer, 2018 issue of Bref. http://www.brefcinema.com/

Figure 1. This photograph of Rivette was likely taken by François Truffaut at around the time that “The Act and the Actor” was written. On the back of the photo, Rivette has noted “septembre 1950 (église de Charonne) (François)”

The Cine-Files, Issue 12 (spring 2017)