Teaching Rosemary’s Baby

Christian Keathley

In the 1992 documentary Visions of Light, cinematographer William A. Fraker describes working for Roman Polanski on the director’s first film in the U.S.

I routinely teach our department’s introductory course, Aesthetics of the Moving Image, a general introduction to film and television analysis. I begin with a film that will, throughout the term, provide clear examples of whatever topic we’re discussing–narrative structure, production design, decoupage, sound, etc. Rosemary’s Baby works very well for this purpose. Plus, very few students have seen it and most like it a lot. I also begin with a short reading that introduces the range of topics under consideration when conducting film analysis, and that also models such analysis in clear and concrete terms–Victor Perkins’s “Moments of Choice.”

The shot Fraker describes from Rosemary’s Baby is one such moment of choice, and his anecdote raises a simple question that he doesn’t adequately answer: Why did Polanski want it that way? Why did he insist on framing Minnie Castavet so that she could only partially be seen through the doorway?

I ask my students to account for this choice. First, I ask them to say not what the shot might “mean,” but simply to describe how it affects the tone of the scene–that is, how it makes them feel. Most are in agreement that the shot is “odd” and makes them feel “uneasy” or “suspicious.” Everything else is the scene is comparatively straightforward, so the shot introduces an element of strangeness into a scene whose cinematic presentation does not call attention to itself in any other way. It doesn’t take long, though, before the students press on to meaning: the fact that we can’t see her face makes us think she’s hiding something, or that something is being hidden. By not giving us a full view of the action, the film creates the sense that we are not being given the full story.

The students’ answers are generally satisfactory, but I want them to see beyond the specifics of any one choice and to consider the ways in which individual choices sometimes fit together with others to form a pattern. “Can you think of any other shots like this in the film?” I ask. “Shots in which we are looking through a doorway and can’t see the full action?” It usually takes a few minutes, but inevitably someone will recall an earlier moment, near the conclusion of Guy and Rosemary’s dinner with the Castavets. Minnie and Rosemary are in the kitchen washing dishes while Roman and Guy sit in the living room, talking and smoking. At one point, Rosemary sets aside a dish she has just dried and looks off toward the living room. We get her point of view:

Again, I ask about this particular choice–description, effect, meaning. We cannot hear what the men are saying, and all we can see is the cigar smoke drifting from around the right door frame. This presentation, someone will offer, creates the impression of a secret conversation. But soon someone else will note that what we understand to be happening here on a second viewing was not apparent to us on the first: it is here, we can infer, that Roman Castavet first proposes to the young actor Guy that if Rosemary will carry Satan’s child, Guy will in turn enjoy success on the stage. Roman has spent much of the dinner earlier in the evening priming Guy by buttering his ego–praising the authenticity of his performance in a supporting part in John Osborne’s play Luther.

But this isn’t the only other shot like this. Early in the film we are introduced to the Woodhouse’s elderly friend Hutch, a fatherly figure in whom Rosemary confides. Over dinner, Hutch regales Rosemary and Guy with tales of horror from the past of the Bramford apartment building where they are moving–“the black Bram.” Eventually, Hutch comes to suspect the Castavets are linked to that past, and he calls Rosemary to arrange a meeting. But on the day of their appointment, he suddenly takes ill and falls into coma. Later in the film, Rosemary gets a telephone call informing her that Hutch has died–and here again, the staging and framing of the action is significant. The scene begins with Guy and Rosemary in their living room. When the phone rings, Rosemary retreats to the bedroom to answer it, but our view does not move with her. As the conversation unfolds, we can hear what she says, but we wait in the living room with Guy. The scene is filmed so the delivery of the news of Hutch’s death takes place off screen, around the corner of the bedroom door frame.

By this point, the students are beginning to see that the “meaning” of any one of these shots is linked to the larger pattern, and their curiosity shifts from a moment of choice in any given scene to the logic of choice in applying this visual pattern to a group of certain selected scenes. When something suspicious happens, they will say, something related to the Satanists and their plot to exploit Rosemary, Polanski often frames from outside a doorway. “But why,” I ask? “Why apply this pattern?”

Still another example–this one with an interesting variation. Early in the film, Guy auditions for a part that he loses to a fellow actor, Donald Baumgart. Then, after Guy agrees to the Castavets’ plan, he gets a call informing him that Baumgart has suddenly gone blind, and that he is now the choice for the part. The framing of the action here is strikingly similar to what we will see later in the film when Rosemary gets the call about Hutch. The phone rings and Guy goes into the bedroom to answer it as Rosemary (and we) wait and listen from outside the bedroom. Here, however, we soon cut to a shot inside the bedroom, with Guy sitting on the bed. The camera then gradually pulls back as Rosemary steps into frame and leans against the door jamb. So why cut inside the room here? Someone will typically offer that the cut inside the room marks the shift from the bad news that Baumgart is blind (thus keeping to the pattern) to the good news that Guy now has the part (thus slightly deviating from the pattern).

But there is one more instance, and that is the scene that sets the pattern. In the film’s introductory sequence, when the Woodhouses visit the Bram, they are told that the building originally consisted of a number of very large apartments, most of which have been broken up into smaller units; and they are also told that the previous tenant of the apartment they are looking at, the elderly Mrs Gardenia, has died only a few days earlier. As they prowl the still furnished apartment, the superintendent notices something odd: a very large piece of furniture has been moved so that it blocks her closet.

The superintendent enlists Guy’s help in moving the piece to gain entrance to the closet, which reveals nothing but the woman’s vacuum cleaner and some towels. Deeply puzzled by the action, the superintendent concludes that the old woman must have been going senile.

So I ask, “How does this scene lay the foundation for the pattern we have been exploring? This shot doesn’t exactly match the others. Or does it?” The attentive viewers will recall that, as the superintendent has noted, the apartments have been broken up into smaller units, and the closet links this apartment to a closet in the Castavets’ apartment. At the film’s climax, Rosemary will remove the shelves and pass through to where the Castavets, Guy, and others are celebrating the new child, Satan’s child–the baby that Rosemary thought she had miscarried. Now, the reason why Mrs Gardenia moved the furniture, and why this shot sets the pattern, becomes clear: bad things are happening on the other side of the door.

Nothing in the subsequent scenes–the ones described above–demands that they be shot the way they have been. Polanski has applied a formal pattern to this group of scenes in the film–a pattern that is prompted by an important plot point in the film’s opening sequence. Through this visual motif, Polanski associates those later scenes with the feeling of mysterious uneasiness and confusion expressed by the superintendent here.

**

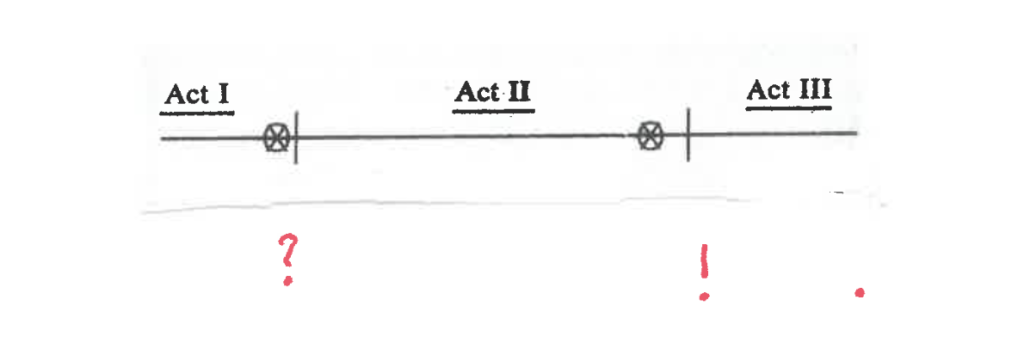

The second week of the course is spent on narrative structure, and this topic offers a good opportunity to reinforce the point about patterning. One of the most common ways in which patterning is employed in feature films is to mark the breaks between acts. I first learned about the use of the three-act structure in scripts from Syd Field’s book Screenplay, which includes this helpful diagram and which I give to my students. In addition, I tell them something that a friend once told me, but that I’ve never found a citation for. Allegedly, Kurt Vonnegut once said that you can understand the three-act structure with three simple punctuation marks: question mark, exclamation point, period.

Rosemary’s Baby follows this narrative structural convention, with act breaks marked by the pattern of Rosemary and Guy’s entrances into the Bramford, the Gothic apartment building in New York where the action is set. This clear pattern is, however, also marked by crucial variations. At the film’s opening, Rosemary and Guy Woodhouse happily enter the Bram, led by the apartment superintendent, to look at an apartment they hope to rent. As they move through the spacious courtyard on this sunny spring day, they are framed widely as they move past a large fountain whose centerpiece features white calla lilies.

I ask, “Where do you think the first act ends?” Students typically just guess, and I have to keep reminding them to think about patterning because they want to focus on plot events. The first act, I propose to them, ends when Guy and Rosemary, returning home from a night out, find a crowd gathered in front of the building’s entrance. To their horror, they see that the young woman Terry–who is living with the elderly Castevets–has committed suicide by jumping out the window of the apartment. Now when I ask, “Why is this the end of Act I?” some thoughtful student will realize it’s because of the setting, not just the action–though the action is surely part of it too. This scene prompts the initial narrative enigma, or the question mark: Why did Teresa, a young woman who seemed so happy and hopeful when Rosemary met her in the basement laundry, suddenly take her own life? But this scene is further significant because it is here that the Woodhouse and Castavet couples first meet. The final shot of the scene presents the two couples, each with the husband supporting the wife: the Castevets in the foreground, standing on the sidewalk in front of the building, and the Woodhouses in the background, marching off into the Bram through its large Gothic archway, swallowed up into its darkness.

[This scene is useful in other ways as well. In asking them to consider the contrasts between the Woodhouses and the Castavets, one can engage students in a discussion about costuming and performance. Also, this scene offers an excellent example of a director using the axis of action for expressive purposes. When the scene begins, with the Woodhouses walking down the sidewalk, the axis is clearly established; but when the Castavets arrive, Polanski crosses the axis and orients us in reverse.]

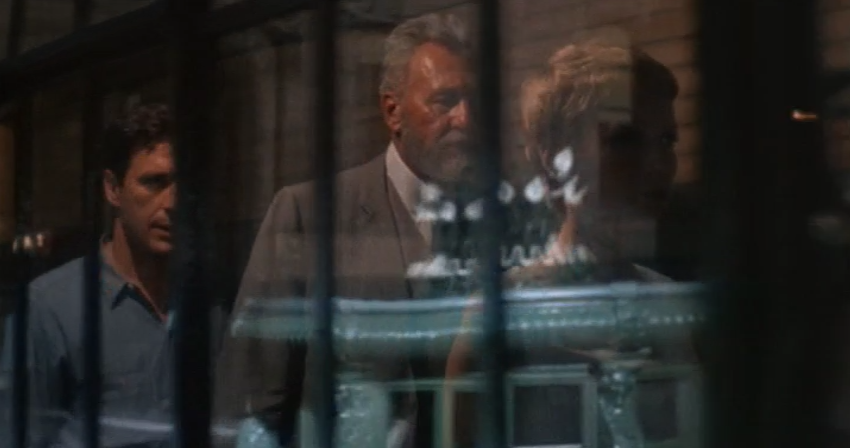

Now that students are alert to the pattern, I ask where the second act ends. “We’ve seen two scenes in which the young couple enter the Bram. Is there a third?” Again, an alert student can get it. The second act ends when Rosemary, having finally escaped the Bram and sought help from her initial obstetrician, Dr Hill, wakes from a nap to discover that Hill has called her husband and Dr Sapirstein, the distinguished society doctor the Castavets have secured for her, to take her back home. In this sequence, Rosemary enters the Bram through a dark narrow walkway that is enclosed by glass and bars, the fountain and its white lilies now a distorted reflection. The prison-like entrapment is clear enough for the students to pick out. But what about plot? What makes it the exclamation point? There are two things: first, we think Rosemary has finally escaped the clutches of the Satanists, but her surprise recapture (and “betrayal” by the good Dr Hill) registers as a shock. Second, once back inside, Rosemary suddenly goes into labor. Her recapture and labor are a striking (even doubled) exclamation point.

But we can further refine the transitions from Act I to II and from Act II to III, because there is a secondary or adjacent pattern. After the scene of Terry’s suicide, we see Rosemary in bed, falling off to sleep, and we are presented with a bizarre and striking dream sequence, one that combines apparent memories and day residue (including the Pope’s visit to NYC, the Kennedys, and the building’s elevator operator) with an actual overheard argument between Roman and Minnie coming through the bedroom wall from next door. At the end of Act II, having sought refuge in Dr Hill’s office, Rosemary falls asleep and enjoys an idyllic dream of holding her baby and surrounded by friends. So, Act I to II transitions with an entrance into the Bram followed by a dream sequence, and Act II to III transitions with a dream sequence followed by another entrance into the Bram.

“Why employ patterning?” I ask. Introductory film studies texts often give it scant attention, and standard film analysis assignments thus too often ignore it. Patterning imposes structure and shape, and these bring a deeper sense of coherence and expressive effect to the narrative. I will often select a few scenes for analysis, and specifically ask the students to consider what pattern the scene might engage with. It could be setting or costuming or shot selection and combination. An awareness of the careful and extensive linkage of individual “moments of choice” across a film’s system of narration is essential for truly insightful film analysis.

Christian Keathley is Professor of Film & Media Culture at Middlebury College. He is the author of Cinephilia and History, or The Wind in the Trees (Indiana UP 2007), and is a founding co-editor of [in]Transition: Journal of Videographic Film & Moving Image Studies.