Chris Marker’s Overnight: Cinétracts Then and Now

Sarah Hamblin

In the voiceover to his 1977 film about the rise and fall of left wing militancy in the previous decade, Le Fond de l’air est rouge, Chris Marker calls attention to the fundamental ambivalence of the images of protest that the film catalogues. Returning to footage from an earlier film, La Sixième face du Pentagone (1968), in which anti-Vietnam protestors successfully break through a military barricade to ascend the steps to the building’s main entrance, Marker calls into question the meaning he’d previously assigned to the images. Commenting on the surprising ease with which the protestors are able to cross the police line, he wonders whether the footage is, in fact, testament to the success of the protest: “I filmed it, and I showed it as a victory for the Movement […]. But when I look at these scenes again, and put them alongside the stories the police told us about how it was they who lit the fires in the police stations in May ‘68, I began to wonder if some of our victories of the ‘60s weren’t cut from the same cloth.”[1] Having learned more of the tactics employed to battle such protestors in France, Marker speculates that the soldiers and police outside the Pentagon may have facilitated this ceremonial victory in order to justify their own brutal retaliation, and he laments how an image once taken as incontrovertible confirmation of the success of a protest could also be understood as evidence of the contrary.

As Jon Kear argues, the commentary on Le Fond is emblematic of Marker’s long-standing preoccupation with the hermeneutic instability of images. Marker’s political films, as much as they aim to document a history of left radicalism, at the same time remain attentive to the uncertainty that any such archive preserves. If, for Kear, Le Fond signifies a shift in Marker’s activism away from films dedicated to raising awareness of contemporary struggles to films invested in exploring and preserving the complex history of these

Movements, Overnight (2012), one of Marker’s last films, arguably signals the culmination of this trajectory. Overnight is a short film, less than three minutes in length, about the 2011 London Riots. Published on Marker’s “Kosinki” YouTube channel, the film is composed from photographs of the riots taken by The Times of London. Formally speaking, Overnight is very basic and was clearly made as a hurried response to the riots. Unsurprisingly, then, its release passed by almost unnoticed, with only a brief mention on Mubi as “Video of the Day.” The opinions of those who did see the film were polarized; for some commentators it was a sympathetic articulation of the violence of a disenfranchised youth, while for others it “felt more like a Tory campaign video” than a piece of oppositional political cinema.[2] Like the footage at the Pentagon in Le Fond, the images that comprise Overnight have been read as affirmations of both progressive and conservative responses to the riots.

Figure 1. Chris Marker, Overnight, Youtube video, 2:42, Posted August 13, 2011.

In this sense, the film is a somewhat perfect representation of the riots themselves, which maintain a similarly ambivalent status in the British political imaginary. The London Riots erupted on August 6, 2011, beginning as rallies against racially motivated police violence and the fatal police shooting of unarmed Tottenham resident, Mark Duggan. Protestors, demanding justice for what they saw as another unprovoked murder of a black suspect, became violent after police accosted a sixteen-year-old girl who threw a bottle at them. These clashes soon escalated as protestors filled the streets, setting fire to police vehicles, buses, and buildings, and looting and vandalizing local businesses. Within two days, riots had spread across London and to other metropolitan centers, including Birmingham, Bristol, Liverpool, and Manchester. Over the six-day course of the riots, five people were killed, approximately 2,500 businesses looted, and over £300 million of damaged caused.[3]

For sympathizers, the riots were pronounced as insurrections against institutionalized racism and as evidence of a failing economic system; they were the “produc[t] of a crumbling nation” in which Britain’s underclass, frustrated with austerity and rampant racial and economic inequality, spontaneously rebelled against a fundamentally unjust system.[4] For most, however, the riots signified nothing so noble. Rather, they demonstrated hooliganism, criminality, and the breakdown of social morality; they were evidence of the UK’s welfare-inspired culture of entitlement and proof-perfect that David Cameron’s Broken Britain was more than just a campaign slogan. Such was the narrative adopted by the media, as right-wing tabloids like The Sun and The Mirror through to more reputable left-leaning broadsheets like The Guardian, all affirmed Cameron’s account of the riots as “criminality, pure and simple.”[5] The Times was no exception, referring to the riots as “an opportunistic display of arson and acquisition” that quickly devolved into “a senseless orgy of destruction.”[6]

These opposing interpretations of the riots are both simultaneously at play in Overnight, and such ambivalence is at the core of the film’s politics. On one level, the film affirms the claim that the riots were nothing but criminal opportunism. However, when considered as a contemporary version of the cinétract—a mode of political filmmaking that Marker pioneered in response to what many leftists saw as the biased news coverage of 1968 – Overnight functions as a foil to the interpretation of the riots circulated by the mainstream media. Moreover, this uncertainty in the film’s presentation of the riots maps onto a similar ambivalence about its quality. Overnight’s formal structure is certainly straightforward; for some Mubi commentators this simplicity camouflaged a surprisingly sophisticated engagement with the riots, while others dismissed the film as uninspired and amateur.

Rather than argue for a particular side in either of these two debates, this essay holds these oppositions in tension and argues that they are fundamental to understanding the stakes of Overnight as a political film. At the level of content, the ambiguity in Overnight speaks to the meaning of the riots themselves, which remain a contested symbol, and to the power of political protest in the wake of the decline of the New Left movements of the 1960s. At the level of form, it speaks to the limits of the cinétract as a mode of politically oppositional filmmaking in the era of new media. Both the form and content of Overnight are therefore reflective of the problematic legacy of 1968 in relation to both protest and political filmmaking, where the methods of opposition that characterized ‘68 function differently under the conditions of the mediatized, neoliberal present. The ambivalences in Overnight thus highlight the need for new modes of political film practice that can respond to the challenges of the contemporary moment.

Overnight from the Right

At first glance, it is easy to see how Overnight affirms the argument that the London Riots were nothing but an expression of base criminality, as it is comprised almost exclusively of before and after shots of vandalism. Indeed, nearly every image in the film is completely bereft of individuals, emphasizing the destruction of property over and against images of people protesting. In this way, the lack of actors in the film calls attention to what seems to have been missing from the riots themselves: clear motivation. Overnight spotlights the effects of the riots but excludes their causal agents. The rioters themselves thus become inconsequential; all that is relevant is the destruction of property and the looting of businesses since this is all the riots were.

There are two moments in the film that imply a sense of action and agency, but they do not clearly challenge the argument that the film presents the riots as the meaningless destruction of property. The first of these is the three photographs of the Union Post Building that conclude the film, this sequence including a singular “during” photograph of the building on fire. Marker animates the transition from the burning building to the burnt-out structure with an iris wipe (all other transitions in the film are dissolves from before to after), but the transitional device is so amateurish that it seems forced. Making the connection between the action of the riots and their aftermath thus appears as an artificial process that can be read metaphorically; since there is no larger political motivation behind this destruction, any attempt to provide a narrative logic that connects the before and the after can only appear as a superimposed, simulated aftereffect.

Figure 2. The Union Post Building on Tottenham High Road. Marker uses an iris wipe to transition from the building in flames to the burnt out structure (Overnight, 2012).

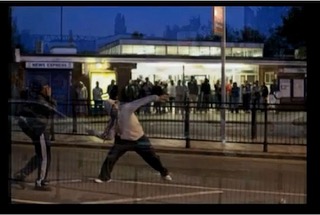

The other image in the film that includes a sense of action – a photograph of a rioter preparing to throw a projectile outside the Tottenham tube station – can similarly be taken to highlight the riot’s lack of political motivation. This image has the most in common with those from Marker’s earlier political documentaries in as much as it is a live action shot of a person engaged in action, but unlike the still photographs in Le Fond or La Sixième face, there’s no voiceover or camera movement to make the image dynamic. Likewise, the camera doesn’t pan across the image to reveal either the protestor’s target or the larger scene in which the rioter is acting. Rather, the image remains static and frozen; the action that it captures is flattened and rendered inert by the stillness of the camera, and the rioter is as motionless as the crowd of people watching in the background. In addition, the image embodies a sense of futility since the rioter is aiming at something we can’t see. Like the absence of actors in the other images, then, the absence of a target in this one metaphorically encapsulates the problem of the riots—they weren’t aimed at anything. As such, Overnight doesn’t represent the rioters or a dynamic sense of action because the rioters aren’t anyone in particular and their actions have no meaning beyond the destruction they caused. Indeed, understanding the film as an expression of the baselessness of the riots also contextualizes its brevity; while Le Fond needs over three hours to work through the intricate network of global forces and ideas that set 1968 in motion, Overnight needs only three minutes to sum up a series of events that lack any such complexity of motivation. Taken this way, Overnight thus affirms the original narrative behind the images that it uses and endorses the mainstream media’s condemnation of the riots as nothing but wanton destruction and opportunism.

Figure 3. An unidentified rioter prepares to launch a projectile outside the Tottenham tube station. (Overnight, 2012)

Such a conservative interpretation of the film makes sense, and the fact that Overnight uses photographs from The Times, a newspaper whose account of the riots affirmed this narrative of criminality and opportunism, could help explain why the film presents the riots in such a politically neutral way. However, this doesn’t take into account the relationship between Overnight and Marker’s other short, political films, which operate according to a particular formal logic. As with a number of Marker’s films, the simplicity of Overnight is deceiving and, as Adrian Martin argues, is actually what makes Marker’s films so challenging to talk about.[7] For if we consider Overnight as a contemporary version of a cinétract, it is possible to discern another meaning in the film, one that counters such an initially conservative reading.

Cinétracts and Simplicity

Cinétracts emerged in France during the 1968 protests as a series of short, anonymous films made from easily produced or readily available materials—rough footage, photographs, collages, and intertitles. Shot quickly using black and white 16mm film stock and edited in camera to keep costs down, each cinétract ran the length of 100 feet of film, which translates to slightly less than three minutes. As Catherine Lupton describes them, these “combative and often strikingly eloquent visual pamphlets” were made in order to respond quickly to events as they unfolded on the streets of Paris.[8] Although numerous prominent filmmakers like Godard and Resnais were involved in the production of the cinétracts during this period, Marker is credited with their conception, and he approached the Estates General of Cinema with the idea, which sponsored their production.

The parallels between these earlier political shorts and Overnight are immediately striking. Despite being produced digitally, Overnight runs the same approximate length as the original cinétracts, and it is similarly a montage of readily available footage. Like the earlier films, Overnight was also clearly made quickly and cheaply as an immediate response to the events as they were happening in London, and the film is likewise unsigned for the same reason, one assumes, as the original films: to mark it as a political provocation rather than an auteurist artwork. The only apparent difference between Overnight and these earlier films is the use of music. Older cinétracts were silent in order to ensure both cheap production and straightforward exhibition. Silent 16mm projectors were relatively inexpensive and had become more common with the rise of film programs at universities; by shooting in this format, the filmmakers associated with cinétracts were able to ensure that these films were screened with relative ease. Given the evolution of filmmaking equipment and new online modes of distribution, however, making a film without a soundtrack is no longer a key requirement for ease of production or exhibition.

If we accept that these parallels are more than coincidence, Overnight asks to be considered in line with the political intent of the original cinétracts. In this context, the images of the destruction of private property in Overnight carry with them an implicit critique of the consumerist ideologies that produce such violent resentment. More importantly, though, the images in the film suggest the fragility of the current capitalist system. The buildings shown are all familiar establishments on most British high streets—chip shops, electronics stores, and major national chains like Nandos, HMV, and William Hill. Such businesses comprise the everyday fabric of the corporate consumer world around us, so familiar and ubiquitous that they seem to be permanent fixtures circumscribing our everyday lives. With its quick transitions from before to after, Marker’s film demonstrates not only that these landmarks of capitalist culture can be destroyed but how quickly and easily this can be accomplished. In this sense, the absence of actors would indicate the speed and ease with which this destruction can be wrought; we can go to bed one night with everything as it usually is and wake up the next day to a whole new world. Change, it seems, can indeed happen “overnight.” That the businesses are all major corporate chains and that no one in particular is shown to cause this destruction implies that this could be anywhere—any British high street at any time—and that anyone could be the one to change it. Indeed, there is only one uniquely recognizable image in the film, the Union Post building on Tottenham High Road, a structure built by the London Cooperative Society in 1930 and since sold to the Carpetright corporation owned by the Conservative peer Lord Harris of Peckham. Yet this specific location also carries with it an implicit political critique, as the building itself becomes a symbol of the neoliberal transfer of power that defenders of the riots mark as their cause. Thus, while champions of private property adopted the burning Union Post Building as the central symbol of the riots’ opportunistic violence, it is also possible to read this image as a rejection of the neoliberal privatization and corporatization of institutions built to safeguard economic justice. Overnight, then, although perhaps not a clear defense of the riots as politically radical, is certainly a reminder that a system that seems so entrenched can be “destroyed” and that anyone can wield this power.

The juxtaposition between the sound and image track in the film helps to reinforce this interpretation. The soundtrack is “Intermezzo” by the Soviet composer, Stanislav Kreitchi. “Intermezzo” was recorded as part of a compilation made by Russian composers who were experimenting with the first Russian synthesizer, the ANS. ANS music was used in numerous Soviet science fiction films, and, as was the case with most synthesizer music in the late 1960s, it was associated with a new, technologically enhanced modernity. When played against images of sites of corporatization and consumption in Overnight, this vision of the future takes on a dystopian valence, as the juxtaposition between the up-beat soundtrack and the images of destruction renders the image track the violent conclusion of a consumerist ideology that can no longer provide people with the luxuries it promised in the 1960s. Riots, Overnight suggests, are what happens when a culture built on consumption collapses and people are left with desires and no way to fulfill them.

This kind of juxtaposition between the sound and image track is reflective of the political intent of the original cinétracts and their Situationist-inspired critique of the mainstream media. As Lupton argues, for the ‘68 protestors, established media was seen as an instrument of capital and the mouthpiece of the Gaullist government, one that affirmed the false promises of consumer society and that skewed coverage of the protests to serve the interests of bourgeois culture.[9] In response, protestors began generating their own newsreels and films as a concrete challenge to what they saw as the inherently biased reportage of the Gaullist news broadcasts. Cinétracts were one such expression of this dissident filmmaking. As Richard Roud describes them, the films were “not individual expressions but oeuvres de combat,”[10] and their function was to counter mainstream accounts of the events taking place in France with reports from a revolutionary perspective.

Taken in this light, the use of images from The Times in Overnight can be understood as more than simply using existent materials in order to ensure a timely response to the events as they unfolded. At the same time, this recycling of photographs operates as a kind of détournement, one that takes the familiar images circulated by the mainstream media and subverts their original associations. By taking up a series of photographs that had already become familiar to the public as the iconic visual record of the riots and compiling them in a way that challenges their mainstream function as evidence of unadulterated criminality, Overnight, like the original cinétracts, attempts to reformulate these photographs as visual evidence of an alternative interpretation of the riots.

Overnight’s simplicity and its amateur aesthetics can similarly be reinterpreted within the parameters of the original cinétract project, which prioritized speed and low-cost production over cinematic complexity. Indeed, as William Wert describes them, the original cinétracts were “more documents than film, more historical moment-preserved than exposition of aesthetic possibilities.”[11] Overnight is certainly not the most sophisticated expression of political cinema, but when understood in relation to cinétracts, the austerity of its style becomes reflective of an approach to political filmmaking that favors sparse production in order to enable the creation of immediate, alternative documents of events that could subvert the biases of mainstream media representations.

The aesthetic simplicity of Overnight relates to another political aim of the cinétracts project, then: the democratization of filmmaking. With the establishment of the SLON film co-operative, Marker became increasingly committed to empowering various groups to represent themselves through collective filmmaking practices. One of the key antidotes to the biases of the French mainstream media was to democratize media production; this involved filmmakers sharing their expertise with various groups and aiding them in the production of alternative media. This in turn required filmmakers to relinquish their commitment to more complex modes of representation as this required sophisticated technological or theoretical knowledge that would automatically discredit such amateur films.

If the idea behind the original cinétracts was to democratize news reportage, the simplicity of Overnight seems to reiterate the same point and to remind us how much easier direct participation in media production is in the contemporary moment. Indeed, unlike the original cinétracts which, although bare-bones, still required some technical know-how, Overnight required only the most basic computer literacy such that the brevity, cheapness, and simplicity of the film can be seen as a testimony to the ease with which, in this technologized, digital age of information, we can make alternative voices heard. If, as Marker has said, a significant portion of his own work is invested in trying “to give the power of speech to people who don’t have it, and, when it’s possible to help them find their own means of expression,”[12] Overnight serves as a reminder that we do not have to confine ourselves to the perspectives of mainstream media and assuming this oppositional voice is, today, astonishingly straightforward. It is significant, therefore, that Marker released the film on his YouTube channel, since the internet has been such a central technology in the fight for media democracy and horizontal communication. Indeed, as Jodi Dean points out, “interactive communication technology corporations rose to popularity in part on the message that they were tools for political empowerment,”[13] and it is possible to position the film within this framework and draw on the internet’s promise of participation, interaction, collaboration and the global reach of platforms like YouTube to position Overnight as a twenty-first century cinétract that attempts to reinvigorate the promise of its 1960s counterpart for the social media generation.

Old Form, New Media

Recognizing the links between Overnight and the cinétract project, however, does not automatically discount a reading that sees the riots as apolitical opportunism. Nor does it necessarily render the film a meaningful expression of political cinema. Indeed, the shifts in technology that have seemingly enabled the idea of participant media that Marker advocated during the height of his political film practice require deeper interrogation. The key differences pertain to changes in the technology used to produce cinétracts, in their exhibition context, and in their intended audience. Taken together, these transformations call into question the political efficacy of the film’s simplicity and thus expose the limits of the cinétract as a contemporary mode of political cinema.

The first major shift concerns the austerity of the cinétract form and its relationship to the technology used to produce them. Cinétracts emerged at a time when there was less reportage and access to the means of production was still relatively restricted. Making films required expensive equipment and technological know-how. 8mm and 16mm were central to the democratization of film production because their relative cheapness and ease of use made filmmaking more accessible. Whereas the production of the original cinétracts required a simple but complete working knowledge of 16mm cameras, Overnight was most likely composed using iMovie or some other similar photo-editing software. If we accept the claim that the simplicity of Overnight is an attempt to remind audiences of the ease with which they can participate in media production, we must also recognize that any such claim is predicated on the use of pre-existing software programs whose straightforward user-friendly interfaces belie a vastly complex back end. Such programs may have been at the forefront of the DIY prosumer revolution,[14] but the extent to which they promote the transformation from passive watcher to active producer and thus redistribute media power has been vastly overestimated.

At its most basic level the problem with such technologies from a radical political standpoint is the non-critical use of such tools. With the back-end so deeply disconnected from the interface, users have no ability to manipulate the program itself and must consent to its preconceived operating logic. This entails accepting not only the design limits of the templates that software programs offer, but also the capitalist structures embedded in the license agreements and terms of use for both design programs and commercial exhibition platforms.

Given the dominance of commercial software and websites related to DIY film production, prosumerism operates predominantly within the logic of consumer capitalism and creates prosumers that have no ability to challenge this condition. Thomas Poell and José van Dijck discuss this issue at length, arguing that the reliance on such social media platforms has done little to actually transform the power structures of the media vis-à-vis the consumer:

While the rise of social media has made activists much less dependent on television and mainstream newspapers, this certainly does not mean that activists have more control over the media environments in which they operate. Media power has neither been transferred to the public, nor to activists for that matter; instead, power has partly shifted to the technological mechanisms and algorithmic selections operated by large social media corporations.[15]

The question of media power is certainly an issue at the level of production where media producers are limited by the template structure of software programs and confined by their user agreements and licensing regulations, but it becomes even more vexed in relation to exhibition where non-commercial alternatives do not command the vast number of users that their commercial counterparts do. Commercial social media sites maintain what Christian Fuchs refers to as “an oligopoly of visibility and attention” that sustains their dominance.[16] While media activists may turn to commercial platforms to ensure the widest possible audience for their work, in doing so they remain beholden to the corporate logic of such companies and thus trapped within an asymmetrical system of power where media corporations work to maximize profit from user-generated content. In relying on commercial media platforms for distribution and exhibition, and to a lesser extent on commercial software programs for production, media activists are vulnerable to monitoring, data collection, and network analysis—Tanner Mirrlees describes Web 2.0 companies as data surveillance enterprises[17]—and to corporate censorship, be it through blocking access and filtering content or through the mechanisms of intellectual property and copyright law.

In the turn towards commercial exhibition platforms, there remains, then, a troubling tension between ease of use and public visibility on one hand and surveillance and control on the other that draws a significant caveat around any claims regarding the potential of prosumer technologies to empower oppositional political expression. The simplicity of the cinétract form may still function as a bid to promote activist participation, but at the same time Overnight’s ease of production and its reliance on YouTube for exhibition cannot be separated from the larger corporate interests that control the use of these technologies and which inevitably circumscribe the film’s political impact.

The turn to online modes of distribution and exhibition also impacts the relationship between cinétracts’ simplicity and their visibility as alternative media. As discussed above, cinétracts were originally conceived as immediate responses to emerging events. In this sense, their simplicity was a major advantage as it allowed films to be produced quickly and thus circulate in a timely fashion; whereas other more complex modes of political film practice would take months, even years, to emerge as counter narratives, the aesthetic austerity of the cinétract form enabled a rapid response, sometimes even pre-empting the mainstream media for whom immediate publication was also not common. Moreover, the simplicity of the form facilitated the ease of distribution and exhibition, enabling the films to be shown with relative ease outside of traditional venues.

In the era of Web 2.0, however, the sophistication of accessible prosumer cameras and editing software and the ease of online distribution means that the original simplicity of the cinétract form is no longer as essential to quick production and, as a result, it now operates differently. Indeed, in today’s hyperlinked digital culture, the ease of basic media production may have led to a proliferation of voices, but it has also made it harder to ensure that anyone is listening. In a media-saturated environment, simple films like Overnight can easily pass by unnoticed. This is due, in part, to the sheer volume of information, which renders simplicity and brevity potential barriers to visibility; simple films are either overlooked or dismissed as crude and amateurish. This was certainly the case with Overnight; unlike Marker’s large-scale new media films, notably the enigmatic and intricate essay film Chats perchés (2004) which was described as his “capstone work” in new media,[18] Overnight was barely noticed and its reception a far cry from the digitextual event that marked the release of Chats perchés. Rather, for one Mubi commentator, Overnight was “dull, uninspired and rather pointless” while another noted that its amateur quality made the film “fee[l] like the work of an old man.”[19]

Under these conditions of proliferation, the voices of oppositional media struggle to be heard and end up contributing to what Jodi Dean describes as the intensive circulation of content that is constitutive of communicative capitalism.[20] She states:

One of the most basic formulations of the idea of communication is in terms of a message and the response to the message. Under communicative capitalism, this changes. Messages are contributions to circulating content—not actions to elicit responses. Differently put, the exchange value of messages overtakes their use value. So, a message is no longer primarily a message from a sender to a receiver. Uncoupled from context of action and application […] the message is simply part of a circulating data stream.[21]

Contrary to digital utopianists, who focus on production and defend the relative ease with which users can contribute to conversations as a radical democratic act, Dean emphasizes circulation and maintains that the proliferation of information is directly proportional to the devaluation of any particular contribution. For Dean, stressing the ability to produce content radically overemphasizes the ability of any contribution to significantly shape a conversation as it “misdirects attention from the larger system of communication in which the contribution is embedded.”[22] Contributing to the infostream may feel like a communicative act because the rhetoric of democracy conditions us to believe that voicing our opinions matters. Under the conditions of communicative capitalism, however, these opinions are actually passive expressions that contribute only to the circulation of information and rarely ever actually communicate.

The problem of circulation that Dean alludes to is amplified in online exhibition contexts, which, as discussed above, favor mainstream commercial sites where content must compete for attention and video activists without substantial economic support struggle to distinguish their work for an audience. At the same time, the simplicity of the cinétract form does little to help such work stand out. Without aesthetic sophistication or mainstream appeal or without the resources to effectively promote it, a film like Overnight struggles to garner critical attention or prompt meaningful discussion. Indeed, it is likely that the limited attention that Overnight has received is only because Marker’s name is attached to it. Without this connection to a prominent filmmaker, I doubt that I would be aware of the film or would consider it worthy of critical discussion. In this sense, the idea that the simplicity of Overnight is a reminder of the ease of participation and an affirmation of its political potential rings somewhat false since such a film, unless anchored to a name like Marker’s, is surely destined to drift by unnoticed in the circulation of information. As such, the goal of fostering participant filmmaking in the 1960s, what Trevor Stark refers to as the “move from a cinema of auteurism to one of autogestion,”[23] today comes up against the problem of visibility, one that is intensified in the media-saturated environment of communicative capitalism where only filmmakers with name recognition are able to stand out. This competition for recognition upholds the commercial function of YouTube as a means of monetizing personal brands while simultaneously undermining the original cinétracts’ rejection of auteurism.

This problem of visibility extends into the shift in exhibition context and the difference between the audiences for the original cinétracts and for Overnight. The original cinétracts were intended for an already deeply politicized and active audience; as Godard describes them, cinétracts were “a simple and cheap means to make political cinema for a section d’entreprise or an action-committee.”[24] The screening venues for the original cinétracts bear out this political intent. While they were shown in more mainstream venues internationally (the Venice and New York Film Festivals and the National Film Theatre in London), in France they were shown on the underground political circuit[25] and screened in factories on strike and at student assemblies, political action committees, and occupations.[26] Cinétracts thus served a dual political function; on one hand they worked to educate audiences and provide a corrective to mainstream media reportage, and on the other they worked to agitate an already mobilized political audience and thus fuel the momentum of the strikes and protests.

Both this audience and the exhibition environment have changed significantly since the cinétract was first conceived, however, and the vision of the cinétract functioning as direct intervention in a concrete situation has waned along with these conditions of spectatorship. Unlike the original cinétracts, Overnight was not screened for the rioters or at protests or debates about the reasons for the violence. As a result, Overnight cannot lay claim to the same goal of political agitation. Rather, it seems to exist for a more politically neutral, or at least politically inactive, audience. The exact contours of its imagined audience are hard to determine, however, precisely because of the dynamics of communicative capitalism; Overnight talks, but it is unclear who it is talking to. The loss of a clear and politically invested audience further emphasizes the previous issue concerning the visibility of Overnight as alternative media, but at the same time it underscores a shift in the function of the cinétract; without this preexisting audience, the cinétract may maintain its educational function but it cannot sustain the same capacity for agitation.

If we accept that Overnight is centered on educating its audience, the stakes of this goal also change along with the shift in exhibition context. Part of the educative function of the original cinétracts was bound to the formation and continuation of political communities, and the alternative screening conditions were central to this as they provided the opportunity for interaction and discussion. The fact that the films were screened in venues where audiences had already made some kind of commitment to action—by being part of the strike or occupation or simply attending the screening—was key to the films’ ability to help sustain political communities. At the same time, screening the films on the underground circuit worked to transform audiences from consumers into activists. As Sylvia Harvey argues in her discussion of radical film culture around 1968, “A film projected in a factory is a rather different phenomenon from a film projected in a cinema, and the former was seen as part of an attempt at breaking down the ‘normal’ relationship that exists in capitalist society between the audience-consumer and the spectacle-product.”[27] The choice to screen cinétracts in these alternative locations was more than a means of targeting a politically engaged audience, then. In addition, it was an attempt to divorce film from its typical consumer-spectacle context and replace it with an activist one, thus affirming the film as a stimulus for political action.

While the online screening context for Overnight may differ from the traditional venues associated with cinematic spectatorship, it is no less commercial and as such, does not disrupt the boundary between activist and consumer in the same way that the alternative underground venues for the original cinétracts did. Since its acquisition by Google, YouTube has deployed a number of strategies aimed at monetizing user-generated content and rendering the site profitable. The most noticeable tactics include the introduction of various layers of advertisements and sponsored videos and the introduction of paid content, but data collection has also been a significant means of revenue generation. Alongside these monetizing strategies, the structure of YouTube’s interface, which profiles users to feed them a new set of topics that will sustain their interest and prolong use of the site, similarly perpetuates the commercial dynamic of the viewing experience. The distinction between viewer and market for commercial sites like YouTube remains blurred and the viewing experience distinctly consumer-oriented.

In addition, the extent to which online viewing is able to replicate the social and public aspects of the kind of activist spectatorship the original cinétracts aimed for is questionable. Whereas the original cinétracts were fundamentally tied to the material spaces of protest, the online viewing context for Overnight offers a radically different mode of sociality that is, as Peter Dahlgren describes it, “networked yet privatized.”[28] While the internet may provide individuals with the ability to interact with others who have watched the film, this interaction remains largely within the realm of the digital, and this kind of participation via the media does not necessarily extend beyond itself. As such, the kind of political participation that a film like Overnight prompts remains largely relegated to passive modes of online engagement—watching, tagging, sharing, commenting—that do not necessarily constitute meaningful political interaction within the online community or lead to material action outside of it. Indeed, as Thomas Poell and José van Dijck argue, commercial media sites like YouTube are ““both technologically and commercially antithetical to community formation.”[29] Any sense of community is only ever temporary as it is “always already on the point of giving way to the next set of trending topics and related sentiments.”[30] Put otherwise, while online discussion may potentially reproduce a version of the collective, public spectatorship of the original cinétracts, in reality, this networked mode of interaction struggles to replicate the same sense of commitment that was generated by the underground viewing conditions, and it rarely ever moves beyond the virtual realm to incite the material forms of connection or protest that were are the heart of the exhibition strategy of the original cinétract project. Taken together, the shifts in production technology and audience, when combined with the turn to online exhibition, indicate that while Overnight may resemble the original cinétract in form, the political implications of this style have dramatically shifted. Consequently, Overnight cannot be taken as the unproblematic return to an earlier mode of political film practice; rather, the changes in production and exhibition point to the limits of the cinétract as an effective mode of political filmmaking in the contemporary moment, rendering it a zombie-form out of time with contemporary politics.

The Ambivalent Legacy of ‘68

Politically speaking, Overnight is an intensely ambivalent film both in terms of content and form, and it returns us to the question of the ambiguity of images that we began with. Understood as a contemporary cinétract, Overnight can be seen as a Gramscian counter-hegemonic representation of the London Riots. However, while Overnight works to make the Times images mean otherwise, situating the film as a contemporary cinétract does not mean that it then reveals a counter-truth, i.e. that the riots were the unequivocal expression of left-motivated class warfare. Rather, the interpretation of the film as an expression of the bankruptcy of neoliberalism and the fragility of the system sits in tension with the claim that the film affirms the riots as baseless violence. In this way, Overnight preserves the ambiguity and the complexity of the riots, articulating their ideological vagaries and criminal opportunism alongside a more radical interpretation. Thus, Overnight doesn’t so much advance a counter-history of the riots as it forefronts the ambivalence of images of protest.

Through its treatment of the images from the Times, the film preserves the ambivalence of the riots themselves as both an event pregnant with political possibility and an empty gesture that underscores the disappearance of organized political protest in the contemporary moment. The absence of connection to a larger political movement is key to unpacking the way that Overnight engages the political stakes of the riots. Without this connection, the London Riots are what Alain Badiou refers to as “immediate riots”—riots that reflect frustration with the status quo and a desire for change, but lack a clear program or ideology and thus remain “violent, anarchic and ultimately without enduring truth.”[31] In this respect, the London Riots align with the 2005 French Riots as an expression of the “pure irrational revolt without any program” that Slavoj Žižek sees as the legacy of May 1968.[32] For Žižek, the anti-hierarchical ideology of ‘68 and its investment in the politics of autogestion and spontaneity were quickly co-opted by a new “spirit of capitalism” to become a mode of human resource management.[33] As neoliberalism transformed autogestive politics from the radical opposition to corporate capitalism to one of its constitutive organizational features, the New Left collapsed. The spontaneity of the London Riots is thus the problematic legacy of a movement that no longer exists, and without this link to a larger affirmative politics, the riots struggle to, as Badiou would put it, move out of their specific time and place and effect a lasting change.

In this way, Overnight operates as a signifier of the problematic legacy of ‘68 in terms of both its politics and its cinema. If the lack of connection to a larger political Idea (in the Badiouian sense) marks the limit of such autogestive spontaneity under current capitalist conditions, the limits of the cinétract form in the age of new media similarly reflect how the legacy of the original cinétracts’ call for media democracy and DIY participation in 1968 has been co-opted by consumer capitalism to form the cornerstone of prosumerist technologies and social media platforms. Just as the film can be interpreted as both an expression of and a challenge to the narrative of the riots as criminal opportunism, the form of Overnight is itself politically ambivalent, on one hand representing the ease with which contemporary audiences can create oppositional media, and on the other the invisibility of these alternative voices within the larger mediascape and the complicity of the tools of production with the forces of prosumerist capitalism.

The return to the cinétract with Overnight is significant, then, for the ways that it highlights the radical difference between 1968 and now, and the risk of transplanting earlier models of political cinema into the contemporary moment without thinking through this historical difference. This is especially true for the cinemas of 1968, whose forms and theories still tend to define the parameters of effective political film practice. Autogestive cinema and participant media remain fundamentally important modes of oppositional filmmaking, but films that revive these practices cannot be celebrated uncritically. In the case of Overnight, the changes in production technology and distribution and exhibition contexts, as well as the larger political climate and the shift in intended audience, must be addressed, especially as they relate to the impact of the form and style of the cinétract today. This is not to dismiss a simplistic film like Overnight out of hand or to deny that such amateur filmmaking is not worth our time or attention. But neither is it to fall into the trap that Philip Lopate warns of where everything that Marker produces is guarded against critical judgment by virtue of his status as a major auteur.[34] Rather, it is to recognize both the strengths and the failings of Overnight and to engage with its political aims as well as to critique them in light of the changes in the political climate and film production over the last fifty years. Ultimately, then, Overnight is perhaps best understood as a diagnostic of the challenge of political filmmaking in the age of new media and a reflection on the need to rethink the foundations of cinétract filmmaking to take account of the changing conditions that shape how such a film circulates today. This is not to dismiss Overnight or the cinétract form tout court, but to call for a more critical engagement with its limits and possibilities as a contemporary mode of film practice.

Sarah Hamblin is Assistant Professor of English and Cinema Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Her research focuses on art cinema, political film, and graphic literatures, emphasizing the relationship between aesthetics, affect, and radical politics. Her work has been published in Black Camera, English Language Notes, Cinema Journal, and Film and History, and she is currently completing a book manuscript on revolutionary filmmaking and the rise of global art cinema in the 1960s.

Notes

- Le Fond de l’air est rouge, second part: les mains coupées (severed hands), directed by Chris Marker (1977; Brooklyn, NY: Icarus Films, 2001), DVD. 58:31.

- Comment on Daniel Kasman, “Video of the day: Chris Marker’s ‘Overnight’ (2011),” Mubi, August 17, 2011, https://mubi.com/notebook/posts/video-of-the-day-chris-markers-overnight-2011.

- Reading the Riots: Investigating England’s Summer of Disorder, The Guardian and the London School of Economics, 2012, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/46297/1/Reading%20the%20riots(published).pdf.

- Mary Riddell, “London riots: the underclass lashes out,” The Telegraph, August 8, 2011, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/law-and-order/8630533/Riots-the-underclass-lashes-out.html.

- David Cameron, “Commons Statement,” BBC News, August 11, 2011, http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-politics-14492789.

- “London’s Burning” The Times, August 9, 2011. http://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/londons-burning-j22gv73h0kd

- Adrian Martin, “Chris Marker: Notes in the Margin of His Time,” Cinéaste 33, no.4 (2008): 8.

- Catherine Lupton, Chris Marker: Memories of the Future (London: Reaktion, 2005), 120.

- Ibid., 119.

- Richard Roud, Jean-Luc Godard. A BFI Book. 3rd ed. (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 157.

- William Wert, “The SLON Films,” Film Quarterly 32 no. 3 (1979): 42.

- Samuel Douhaire & Annick Rivoire, “Marker Direct: An Interview with Chris Marker,” Film Comment 39 no. 3 (May–June 2003), 39.

- Jodi Dean, “Communicative Capitalism: Circulation and the Foreclosure of Politics,” in Digital Media and Democracy: Tactics in Hard Times, ed. Megan Boler (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2008), 110.

- The term “prosumer” emerged in the 1980s when the distinction between “consumer” and “producer” was becoming increasingly blurred. The term has since taken on a variety of meanings, but it is most commonly used to refer to amateur consumers who purchase professional grade equipment or to consumers who simultaneously function as creators of the products and services they consume.

- Thomas Poell and José van Dijck, “Social Media and Activist Communication,” in The Routledge Companion to Alternative and Community Media, ed. Chris Atton (New York: Routledge, 2015), 534.

- Christian Fuchs, OccupyMedia!: The Occupy Movement and Social Media in Crisis Capitalism (Alresford, UK: Zero Books, 2014), 138.

- Tanner Mirrlees, Global Entertainment Media: Between Cultural Imperialism and Cultural Globalization (New York: Routledge, 2013), 238.

- Margaret Flinn, “Signs of the Times: Chris Marker’s Chats perches,” Yale French Studies 115 (2009): 103.

- Comments on Kasman, “Video of the day.”

- Dean, “Communicative Capitalism,” 103.

- Ibid., 107.

- Ibid., 109.

- Trevor Stark, “Cinema in the Hands of the People”: Chris Marker, the Medvedkin Group, and the Potential of Militant Film,” October 139 (2012): 133. The concept of autogestion originates with Henri Lefebvre as part of his larger critique of Stalinism and Third Way reformism. Lefebvre offered autogestion as a mode of collective, decentralized, spontaneous, and autonomous democratic governance. These ideals became central to the radical anti-party politics of the ‘68 protestors and were echoed in the political cinema of the period, which similarly favored collective and de-professionalized modes of production that were more spontaneous and self-directed. For more on the politics of autogestion, see Henri Lefebvre, “Theoretical Problems of Autogestion,” in State, Space, World: Selected Essays, ed. and trans. Neil Brenner and Stuart Elden (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 138-52.

- Qtd. in Ibid., 140.

- Roud, Jean-Luc Godard, 157.

- Wheeler Winston Dixon, The Films of Jean-Luc Godard (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997), 103.

- Sylvia Harvey, May ‘68 and Film Culture, (London: British Film Institute, 1980), 28.

- Peter Dahlgren, The Political Web: Media, Participation, and Alternative Democracy (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 63.

- Poell and van Dijck, “Social Media and Activist Communication,” 534.

- Ibid.

- Alain Badiou, The Rebirth of History: Times of Riots and Uprisings, Trans. Gregory Elliot (London: Verso, 2012), 21.

- Slavoj Žižek, Living in the End Times, (London: Verso, 2010), 364.

- Ibid., 356.

- Philip Lopate, “Chris Marker’s Staring Back,” Film Comment, November/December 2007, http://www.filmcomment.com/article/chris-markers-staring-back/