Introduction to Dossier

Steven Rybin

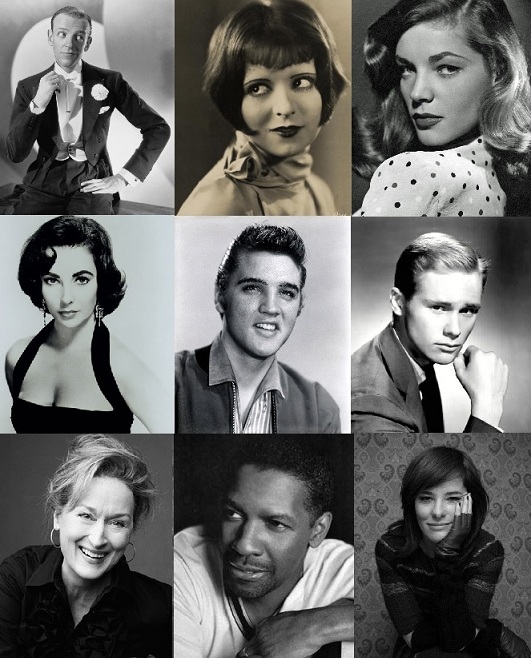

From top left to bottom right, the stars of our show: Fred Astaire, Clara Bow, Lauren Bacall, Elvis Presley, Brandon De Wilde, Meryl Streep, Denzel Washington, Parker Posey.

For this special issue on performance in The Cine-Files, top scholars working in film performance and star studies were invited to write a short piece on an actor of their choice. The impetus behind this idea was to explore the various places occupied by the actor in the intersection of contemporary cinephilia and academic film studies. Cinephilic writing often takes the director’s way of seeing or the medium’s ontology as points of critical departure. What place does the performer occupy in our love for cinema? The pieces in this dossier think about the pleasures taken and the meaning made when we as scholars and writers turn our attention to individual actors.

Our authors cover a range of personalities and historical eras: the silent era (Clara Bow); classical Hollywood during the thirties (Fred Astaire), forties (Lauren Bacall), and fifties (Elizabeth Taylor, Brandon De Wilde, Elvis Presley); contemporary Hollywood (Meryl Streep, Denzel Washington); and American “indie” film (Parker Posey). While the dossier limits itself to actors in the American cinema (past and present), the range of themes, forms of gesture, and approaches to performance explored in these pieces are nevertheless (as one might expect from our roster of scholars!) quite expansive: youth (De Wilde); age (Streep); dance (Astaire); walking (Bacall); the conveyance of emotion (Taylor); race (Washington); sexuality and off-screen scandal (Bow); place and independence (Posey); and the intersection of cinema and rock ‘n’ roll (Presley).

Before introducing these essays and their themes in greater detail, however, it is best to start with the actors themselves. Here is the complete list of performers discussed in this dossier, arranged in order of birthdate:

- Fred Astaire (1899)

- Clara Bow (1905)

- Lauren Bacall (1924)

- Elizabeth Taylor (1932)

- Elvis Presley (1935)

- Brandon De Wilde (1942)

- Meryl Streep (1949)

- Denzel Washington (1954)

- Parker Posey (1968)

These names and dates point to certain tendencies in the selection of actors for our dossier. There is (the inclusion of Streep, Washington and Posey aside) a notable preference for the classical cinema among our authors; in the age of intensified continuity in contemporary Hollywood cinema, which tends to fragment gesture and movement, perhaps the relatively expansive time and space afforded to the actor in classical filmmaking holds attraction for the scholarly film lover. (Of course, many of our esteemed authorshave tackled questions of performance in contemporary cinema in other books and essays.) And our authors remain, for the most part, steadfastly devoted, at least within the context of the present dossier, to film. An exploration of performance in television and new media might indeed justify a separate dossier.

Each piece establishes a different kind of writerly relationship between its author and the actor in question. Robert B. Ray kicks off the dossier with “Notes on Fred Astaire.” Beginning his piece with a contextualization of Astaire in the history of twentieth-century popular music, Ray deepens our appreciation of the cinema’s most talented dancer by drawing attention to the actor’s relatively neglected status as a singer, his early struggles to establish a vibrant sexuality on stage and on film, and his eventual pairing with Ginger Rogers. Ray’s vivid writing, familiar to any reader of his books, is the perfect companion to Astaire’s graceful movements; his essay appropriately concludes with an especially rich look at the “Isn’t This a Lovely Day (To Be Caught in the Rain)?” number from Top Hat.

Astaire is often recognized as one of the classical cinema’s greatest performers. By contrast, in “Clara Bow in Mantrap,” Naremore reminds us how often Clara Bow’s acting skills have been forgotten due to the tendency of literature on Bow to focus on her off-screen private life. Naremore recognizes the importance of that off-screen persona, offering commentary on her early life, but focuses the balance of his essay on Bow’s early career as an actor, placing special emphasis on her underappreciated and unusual comic style. Naremore turns his attention to Mantrap, a 1926 Victor Fleming film based on a serious novel, as a case study for how to appreciate Bow the performer, carefully drawing the reader’s attention to specific gestures, movements, and expressions that vivify not her off-screen affairs but rather her underappreciated screen presence.

Arriving in Hollywood more than two decades after Bow’s first film, Lauren Bacall became, in the forties, a major Hollywood star, appearing in her first film at the age of 19, opposite future husband Humphrey Bogart in To Have and Have Not. As Joe McElhaney reminds us in his piece “Lauren Bacall: The Walk,” Bacall’s screen image was initially marketed by Warner Bros. under the label “the look,” emphasizing her tendency to lower her chin while offering a challenging gaze to the beholder. Although recognizing the importance of “the look” to any appreciation of Bacall, McElhaney shifts emphasis to her walk: the unique way she had of moving on the screen, and the pleasurable, quicksilver intensity this offers to a viewer attuned to it. Focusing his insight on a range of Bacall films, McElhaney shows how the walk works in Bacall’s performances for various directors, such as Howard Hawks, Vincente Minnelli, and Jean Negulesco.

Around the same time Lauren Bacall made her first screen appearance in To Have and Have Not, Elizabeth Taylor charmed audiences in her early films (Lassie Come Home, 1942; National Velvet, 1944). In “Elizabeth Taylor: ‘My Kind of Acting,’” Sharon Marie Carnicke, paralleling Naremore’s discussion of Clara Bow, notes how critics have traditionally preferred to discuss Taylor’s off-screen appearance (in particular, her physical beauty, marriages, and fluctuations in weight) rather than her acting achievements. Carnicke, however, directs our attention to what Taylor accomplishes on-screen, focusing her profile of Taylor on her performance in the 1954 film Rhapsody. Carnicke perceptively demonstrates, in her close analysis of two scenes from Rhapsody, Taylor’s remarkable and memorable ability to convey emotion.

Bacall and Taylor bring the dossier to the 1950s, the time period that provides the stage for our next two actors. In his piece “The Early Elvis Presley Movie: Star as Genre,” Will Scheibel shows how Presley’s larger-than-life public reputation in rock ‘n’ roll provided the context for the creation of a new type of film: the “Elvis movie.” Scheibel uses this cycle of early Elvis films as a way to analyze the genre function a star like Presley embodies. Presley’s cinematic appearances, as Scheibel shows, followed in the footsteps of established rebels such as James Dean, Marlon Brando, and Montgomery Clift. The essay’s close attention to production context and star persona not only paints a vivid picture of Presley’s distinctive contribution to this lineage, but also points to Presley’s original contribution to the historical intersection between film and popular music.

If Presley draws our attention to the youth culture of the fifties, Murray Pomerance explores youth of a different sort in his piece, “Brandon De Wilde: ‘Eloquent of clean, modern youth’.” Pomerance’s essay, which takes its subtitle from a Bosley Crowther review of De Wilde’s 1963 appearance in Hud, notes the striking rarity, relative to the surfeit of child stars in contemporary film and television, of child actors in classical cinema. De Wilde, as Pomerance’s beautifully written contribution shows, was among the most striking and memorable of these. As Pomerance writes, “To both stage and screen De Wilde brought a certain palpable innocence coupled with a directness and physical attractiveness” that was amenable to a wide variety of narrative situations. As readers of Pomerance’s many books and essays on film should expect, the essay provides a vivid portrait of the relationship between De Wilde’s work as an actor and the styles of the various films in which he appeared.

If Presley and De Wilde remind us of youth, Meryl Streep reminds us of the perils an actor may face in her later career. Karen Hollinger’s contribution, “Meryl Streep: Career Renaissance” serves as a follow-up to the chapter on Streep in her 2006 book The Actress: Hollywood Acting and the Female Star. As Hollinger notes, her earlier volume found Streep at a crucial juncture in her film career. On the one hand, her acting career began with strong characterizations of progressive and complex women, in films such as Silkwood and Out of Africa; but on the other hand, by the time of Hollinger’s book, Streep’s career had, in the author’s words, “stalled with her assumption of maternal roles.” In this piece, Hollinger astutely argues that Streep’s recent characterizations contain deeper layers of complexity than the relatively more melodramatic roles offered to Streep in the late nineties and early 2000s.

While Hollinger focuses on the roles offered to a major actor like Streep late in her career, Cynthia Baron’s essay, “Denzel Washington: Notes on the Construction of a Black Matinee Idol,” explores the relationship between stardom and race. As Baron shows, Washington’s stardom evolved in the context of standardized Hollywood practices that enabled his stardom but also prevented him from performing on-screen romances with white women. However, Baron argues that these culturally and industrially determined aspects of Washington’s career, rather than serving as limitations, direct our attention to the “grace, dignity, humanity, and inner strength” of Washington’s characters. Using Washington’s star turns in Mo’ Better Blues, The Pelican Brief, and Philadelphia as her touchstones, Baron persuasively demonstrates how Washington remains a privileged case study for the exploration of race and stardom in the contemporary Hollywood landscape.

The dossier concludes with my essay, “Parker Posey: New York Flight,” which looks at Posey’s performances in independent films set in and around New York City. I attempt to show, through close attention to her performance style and its placement in the city, how traits framed negatively by the narratives in her supporting roles in Hollywood movies (assertive independence, witty intelligence, challenging femininity) become positive performative virtues in her leading roles in independent films. Through a close look at three of her most memorable roles, I describe how Posey’s movements, gestures, and expressions draw the viewer into the excitement of the present moment and its existential possibilities, and away from overarching goals and normative narrative functions.

* * *

All of our contributors, when writing on their actors, choose to focus, at one point or another and to varying degrees of emphasis, on gestures, movements, and expressions – that is, the way in which each actor inhabits various filmic worlds as imagined by various film directors, producers, and writers. Work on performance, of course, cannot ignore a larger historical, industrial, and cultural context, as each piece in this dossier variously illustrates. But the enduring value of cinephilic approaches to performance may be this: the ability not only to capture the way a particular beloved figure moves, looks, and expresses herself in the world, but to embody the experience of these performances in styles of writing alive to the vivid particularity each actor offers our experience.

Steven Rybin is an assistant professor of film at Georgia Gwinnett College. He is the co-editor, with Will Scheibel, of Lonely Places, Dangerous Ground: Nicholas Ray in American Cinema (SUNY Press, 2014) and author of Michael Mann: Crime Auteur (Scarecrow Press, 2013), among other books, book chapters, and articles. He is currently writing a book on the performance of courtship in classical Hollywood cinema.