Good Time Gals

SPRING 2012, ISSUE 2

–Jae Matthews

I’m afraid. Don’t ask why, I won’t tell you. — Jane in Les Bonnes Femmes (Claude Chabrol, 1960)

I remember being a sixteen-year-old girl in love. At that time love could have killed me, but it’s really not what you think. This pubescent moment, defined by its lusty unease and ambiguous dread, finds its way into much of my work.

Today, I revisited Les Bonnes Femmes (The Good Time Girls) and this sixteen-year-old girl, she came back. Claude Chabrol’s notable New Wave classic is all things delicate, fearful and, of course, completely fatalistic. By no means am I saying that the film embodies a substance sensible only to young, precocious women. Rather, the film is for those who wait for love, those confined in their breathless, bated stance for romance. Made for me at sixteen, or always.

Les Bonnes Femmes combines the ethos of realism and absurdism, with careful perversions of classical conventions to make a film that we both recognize and deny. At the very moment we begin to understand the story, Chabrol shatters the narrative and turns the film into something much darker. This film is my favorite form of French New Wave, being both political and humanistic—and honest. The film portrays four women, all remarkably different, but all willing to give in to certain tragic sacrifices for romance. Chabrol gives us men who are both cruel and savage, either harassing the women or abusing them; there is a fine line here between rape and play, trust and death. The storytelling is both clever and dark: it depicts love in its most discomforting, unstable of forms. Possibly the most endearing mechanism of the film is the fact that Chabrol obviously loves these women, without objectification or fetish. It’s a treat to watch a film with female protagonists, without the overused Hollywood happy ending or dependence on men. In Les Bonnes Femmes, our gals’ reliance on men is actually what gets them into trouble… it’s the age-old tale of desire kills the cat, or women are taught to want something (“Romance”) that will pacify, and ultimately harm them.

Not only has Chabrol significantly influenced my work in terms of content, but also in terms of his rules of production. The French New Wave borrows both from the realist standards of shooting in the street (low impact shoots and a dazed documentary style of capturing the public) and from the deep focus of classic cinema. In Les Bonnes Femmes there is an incredibly long sequence in which our girls are riding the train, but they exist as mere elements in the background of anonymous citizens going about their day. Throughout the film, Chabrol gives us these wonderful snippets of Parisian life, which play well in juxtaposition with his absurdist use of classic convention. Where these “newsreel” segments give the narrative a more arbitrary, anonymous feel, the archetypal Hollywood style assigned to our characters’ romantic tales feels cynical and doomed—for it exposes both the needs of the character and the wants of the audience. The softly-lit close-ups or the saccharine interludes could be drawn straight from a Hollywood romance. But, luckily they’re not, because in this world there is no tenderness without penance. This deconstruction is what I find the most electrifying about Chabrol’s work and what I end up taking the most from.

I share here a clip (linked below) from an early movie I made, an obvious tribute to Chabrol (it’s a film where loneliness ends a woman’s life), so we can all revel in my pretty sincere attempts at mystery. I’m allowed to be a little flippant in regard to my own work and this piece in particular will always feel naïve and dilettante. What I attempted to do with this film, My Bird, was set up a scenario that we recognize, “woman meets man,” then violently deconstruct the understanding of what we are watching. This spirit came from Chabrol. For it seems Chabrol’s tendency to leave the audience in perverse suspense, as in Les Bonnes Femmes, became an essential characteristic of his films. I find his laws of subversion to be at once a celebration of true humanity, and a disastrous play on Hollywood ethics.

As Chabrol did with Les Bonnes Femmes, I used violence as a mechanism to comment on the representation of women. Annabelle, much like Jacqueline, is alone, skeptical and waiting to be snared in a fruitless amorous adventure. In Chabrol’s narrative, the sweetest type of affection ends in death; however, there is nothing sensational about this murder. The incident is almost absurd, but it emphasizes the brutality that lies behind the benign, idyllic love that’s only made in movies—a standard that places women in the arms of stupid brutes or passionate killers, believing in the all encompassing “reason of romance.” Convention doesn’t always necessitate the woman’s death, but it does teach her to wait, to be passive and believe in superstition. Chabrol garners a cynicism that aims to eliminate these myths and destroy their illusions. This is what I attempt to do myself.

There’s no shame in mimicking Chabrol’s cynicism, because I believe his politics are still quite relevant. I don’t believe that women or even romance are represented properly in current cinema; convention is careful not to posit a lonely, desiring woman. The honest experience of love is uncertain and fearful; its presentation should be both desperate and ambiguous.

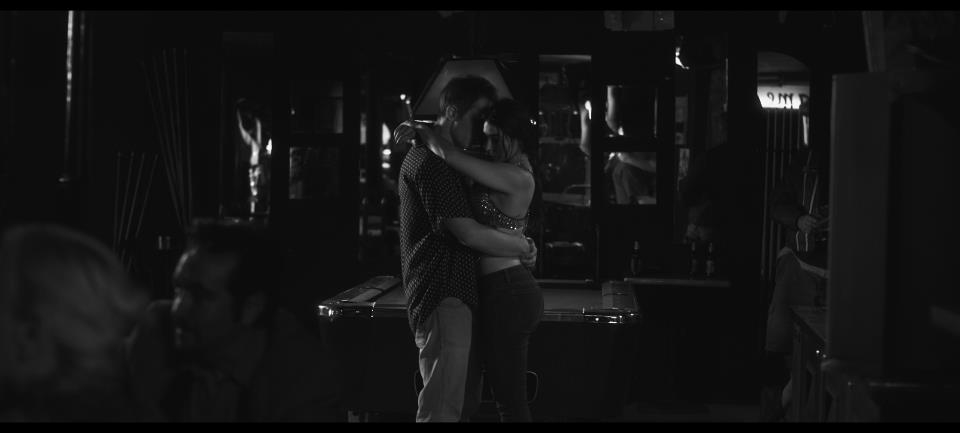

The second clip (linked below) that I’m including comes from a film that I just completed, Alice. Hopefully a little more aware and nuanced than the first example, Alice also deals with the nature of romance and lonely women. Yet, unlike My Bird, I didn’t want to kill anybody. Instead, I wanted to explore the world of romance without metaphor. It was my intention to create an honest and uncomfortable vibe—one that I am sure many would recognize from their futile nights in empty bars. Alice, our lead, is allowed both to desire and to experience her cyclical emptiness. We used untrained actors, and pushed improvisational scenario, much as Chabrol did to get the most intimate performances out of Les Bonnes Femmes. The story itself is one without judgment, nor an easy marginalized ending; Girl + Boy doesn’t necessarily equate to forever.

One could say that Chabrol’s films are not about love, but encounters—this is where I see my work. It’s important that Alice has her night in Alice, as it’s important that Annabelle has her night in My Bird. There’s a sadness to incident, of course, but there’s a reconstruction that occurs with the hiccup of cinematic reason. Interesting filmmakers deconstruct the social canon, and remark on romance.

But perhaps I’m too cynical. I’m relying on a girl who wall-flowered her way into sexuality. For her, love was merely an encounter at sixteen, the open-mouthed hunger of loneliness and the desire to keep it in the dark: quiet and suspenseful.

Posted on May 28, 2012

_____________________________________

Jessica Matthews (otherwise known as Jae) is a student in the MFA program in Film and Television at the Savannah College of Art and Design. Her films draw from a palette of nuanced pain and unsentimental tenderness, and she’s not afraid to leave the viewer eating her dust.