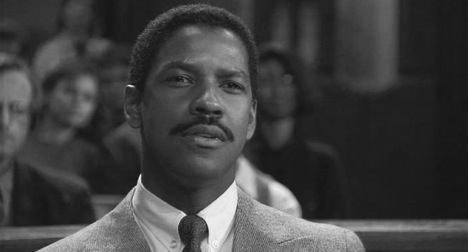

Denzel Washington: Notes on the Construction of a Black Matinee Idol

Cynthia Baron

Donald Bogle describes Denzel Washington as an actor who reconfigured “the concept of classic movie stardom.”[1] His observation suggests that as a consequence of Washington’s career, Hollywood stardom no longer requires a link with whiteness, but can now emerge from screen performances that have “liberated black images from the shackles of ghettocentricity and neominstrelsy.”[2] Washington’s body of work, which includes regular-guy roles in films such as Devil in a Blue Dress (1995), He Got Game (1998), John Q (2002), and The Taking of Pelham 123 (2009), transcends the predator-saint categories generated by white norms. As a “star performer,” Washington has come to embody a residual and alternative vision of black masculinity grounded in skill and mastery of technique[3] His performances recall the grace and proficiency of Bill Robinson, a performance mode lifted and popularized by Fred Astaire.[4] Washington’s career thus provides a site for interrogating larger questions of identity and mainstream representation.

Bogle’s observation that Denzel Washington reshaped “classic movie stardom” also intimates that Washington is best understood as an earlier iteration of romantic leading man, in part because his characters tend to share emotional, rather than physical intimacy with female characters. To understand that emphasis, one might recall that Washington was born in 1954, the year Brown v Board of Education made school segregation unconstitutional and the year Joseph Breen retired after twenty years as head of Hollywood’s Production Code Administration. While these events signal change, the bigotry ingrained in Hollywood conventions, which were and are designed to preempt objections from vocal constituencies, have meant that Washington has had the ability, demeanor, and physicality to play leading parts, but that his roles have rarely included the standard scenes of physical intimacy between the male and female stars.

Hollywood’s standardized representational and business practices have, arguably, widened Washington’s appeal, and made him a matinee idol comparable to stars like Cary Grant. Because love scenes have been generally off limits, Washington’s portrayals have highlighted the personhood of his characters, who implicitly draw their talent, strength, and problem-solving strategies from African-American cultural traditions. Because Hollywood conventions have censored scenes of physical intimacy, Washington’s performances have revealed his ability to convey emotional intimacy and thus increased his romantic allure.

With Washington born the year of Brown v Board of Education and the change in censorship personnel, his image reflects its specific social and institutional context, which is different from the settings for the careers of Paul Robeson or Sidney Poitier and from the career of an actor like Jamie Foxx. For example, Washington was in grade school when Poitier won his Academy Award for Best Actor in 1963. Two decades later, Washington had received his Best Supporting Actor Oscar for Glory (1989) before films like Boyz n the Hood (1991) and New Jack City (1991) were even released. Washington’s theatre work includes an Obie Award in 1982 as a member of the Negro Ensemble Company’s production of A Soldier’s Play. His career as a screen actor began in the early 1980s, a time between Blaxploitation and New Black Cinema, when Eddie Murphy was taking Richard Pryor’s place as Hollywood’s most successful black comedic actor.

It might seem odd to suggest that representational constraints have shaped Washington’s star image. He was named “the sexiest man alive” in People magazine’s 1996 survey (Brad Pitt 1995, George Clooney 1997) and “entertainer of the year” by Entertainment Weekly in 2002 (Nicole Kidman 2001, Lord of the Rings cast 2003). In polls done by PR firm Harris Interactive, Washington has been identified as one of America’s top ten favorite actors every year but two since 1995; he was named America’s favorite star in 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2012, ranking above Clint Eastwood, Tom Hanks, and Johnny Depp. He has won Black Reel and BET awards, NAACP Image awards, Golden Globe and film critics’ awards. In addition to his Best Actor Academy Award for Training Day (2000), he has a Best Supporting Actor nomination for Cry Freedom (1987), and Best Actor nominations for Malcolm X (1992), The Hurricane (1999), and Flight (2012).

Yet observers often see Washington’s roles as reflecting the presence of racist norms, even in cases such as the 1980s St. Elsewhere series or the 1993 Kenneth Branagh production of Much Ado About Nothing, when Washington’s appearance as the token black actor is meant to signal a break with traditional casting. Critics also identify racist norms as the reason films avoid scenes of physical intimacy between Washington and a white female costar, with the absence of scenes with Julia Roberts in The Pelican Brief (1993) or with Kelly Lynch in Virtuosity (1995) perhaps the most discussed instances. Hollywood’s established convention of onscreen segregation makes the mostly implicit physical intimacy between Washington and Kelly Reilly in Flight a curiosity; Flight’s oddity is a reminder that “Hollywood’s permissible field of representation is demonstrated as much by the topics that the industry [has] avoided as by the images that eventually fill the screen.”[5] Although criticized for fostering liberal values, Hollywood’s “permissible field of representation” and the star image of black actors like Denzel Washington continue to be shaped by the bigotry molded into Hollywood conventions.

Washington’s career reflects a specific stage in the ongoing conflicts between Breen-generated practices and the egalitarian values of the civil rights movement. It also reflects Washington’s negotiations with those conditions. With his co-starring or secondary roles in Carbon Copy (1981), A Soldier’s Story (1984), Power (1986), and Cry Freedom showing that he was a skilled actor, Washington was able to secure the leading role in The Mighty Quinn (1989). However, with Hollywood practices still shaped by bigotry, Washington’s first role as a romantic leading man went unnoticed. The Jamaican detective story earned only $4.5M at the box office. Washington and his agent had underestimated entrenched practices: MGM did not expand distribution beyond the opening weekend’s 234 theatres, having determined before the film’s release that it was suitable only for “ethnic audiences.”[6]

Washington’s role in For Queen and Country (1988), which put him at the center of the narrative and made the courtship between his character and a neighbor played by British actress Amanda Redman central to the story, was another miscalculation on the part of Washington and his agent. The film made less than $200,000, with Atlantic Releasing placing it in only 33 theatres. Atlantic’s decision reflects its view that the film had a limited audience, even though the distributor had developed strategies that same year to secure a $2.3M box office gross for A World Apart (1988), which focused on whites battling apartheid.

Washington’s subsequent roles as a romantic lead in Mo’Better Blues (1990) and Mississippi Masala (1991) were also not marketed to mainstream audiences. Spike Lee’s film made $16M; Mira Nair’s made $7M. These box office returns confirmed that Hollywood business practices would continue to be shaped by racist norms, and that Washington’s romantic portrayals would, as a consequence, reach only a limited audience. With starring comedic roles going to Eddie Murphy, and parts in urban crime films going to younger actors, from the 1990s forward Washington appeared primarily in films that established his association with characters known for their wit, determination, ethical decency, and ability to share emotional intimacy with colleagues, friends, and family.

The Pelican Brief was the first of many films that offered that opportunity. With prices adjusted for inflation, the film remains the top grossing movie in Washington’s career. Its onscreen segregation of the co-stars also exemplifies Hollywood’s ingrained racist conventions. As John McWhorter noted at the time: “If Julia Roberts had been costarred with absolutely any attractive white male working in Hollywood, a romantic angle would have been assumed [yet] there was America’s black matinée idol . . . on screen with lovely Julia Roberts . . . and the two of them are ‘friends.’”[7] (108). bell hooks saw the main characters as “completely allied with the existing social structure of white-supremacist patriarchy” because there was no romance despite Washington being “‘the black male sex symbol” of the period.[8] Those observations are entirely right, and yet Washington’s performance as the quietly determined reporter also filled Hollywood screens with an image that did not conform to stereotypes of African American men as predators, saints, or buffoons.

That same December, Washington’s co-starring role in Philadelphia (1993) was another instance when Hollywood strictures on representing black romance helped to establish Washington as “a regular guy” audiences could identify with and as a classic movie star. With Hanks portraying the character identified with non-normative sexuality, Washington became associated with broad-based social and even sexual norms. His character offered a point of identification for a range of audiences, in that Washington, who goes from being a close-minded ambulance-chasing lawyer to a compassionate and effective agent of social change, embodies the film’s narrative arc in which homophobic beliefs are supplanted by a respect for all individuals’ civil rights.

A few years later, Courage Under Fire created another occasion when Hollywood conventions led Washington to become the focus of audience identification. In the film, Meg Ryan is a medevac pilot posthumously awarded a Medal of Honor. The film cleverly keeps Ryan and Washington connected, but distant as it traces Washington’s investigation of events surrounding the crash. With Ryan in the story about changing gender and social norms, Washington becomes associated with broad-based values as the film comes to center on the story of Nat Serling, a tank commander haunted by guilt for covering up a friendly-fire incident he ordered. Washington’s performance conveys the character’s faltering journey from denial and isolation to responsibility and reconnection with family. As expected, the black character’s family life is conveyed briefly, in a series of scenes between Denzel Washington and Regina Taylor that together last less than ten minutes. Yet despite Hollywood’s standardized deference to white audiences, the scenes with Washington and Taylor create a rich narrative about a black married couple’s loss and renewal of physical and emotional intimacy, and their reunion signals the close of the narrative.

Washington’s performances in films like John Q (2002) and The Taking of Pelham 123 (2009) also conform to Hollywood conventions by eliminating the romantic dimension of the black couple’s relationship. Yet with Washington portraying “a regular guy,” he again becomes identified with characters that possess the emotional depth required to face universal ethical dilemmas, and films such as these tacitly make black family dramas stand in for American family dramas. Thus, despite being designed not to offend the widest and whitest audience, Washington’s body of work is, arguably, anchored by a series of portrayals that reconfigure images of black masculinity and “classic movie stardom.” Although Washington’s heavily censored matinee idol image is antiquated by 21st century norms, it reflects the specific options, challenges, and negotiations in Washington’s career. With romance and physical intimacy off limits, over the course of his career Washington became associated with characters defined by their grace, dignity, humanity, and inner strength. Thus, in Washington’s case, his image as a matinee idol and a star known for commitment to family and community has been constructed, at least in part, by the racism in Hollywood’s conventions and business practices.

Cynthia Baron teaches in the Department of Theatre and Film and the doctoral American Cultures Studies Program at Bowling Green State University. She has recently completed a book on Denzel Washington for the Palgrave Film Stars series. She is co-author of Reframing Screen Performance (2008) and Appetites and Anxieties: Food, Film and the Politics of Representation (2014). She is co-editor of More Than a Method: Trends and Traditions in Contemporary Film Performance (2004) and editor of The Projector: An Electronic Journal on Film, Media, and Culture.

[1] Donald Bogle, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies & Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in American Films 4th edition (New York: Continuum, 2004), 123.

[2] Melvin Donalson, “Denzel Washington: A Revisionist Black Masculinity,” in Pretty People: Movies Stars of the 1990s, ed. Anna Everett (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012), 66.

[3] Christine Geraghty, “Re-examining Stardom: Questions of Texts, Bodies and Performance,” in Reinventing Film Studies, eds. Christine Gledhill and Linda Williams (London: Arnold, 2000), 183-201.

[4] For further discussion of these performance modes, see Todd Boyd, The New H.N.I.C (Head Niggas in Charge): The Death of Civil Rights and the Reign of Hip-Hop (New York: New York University Press, 2002); Richard Dyer, Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society (London: British Film Institute, 1986); and Krin Gabbard, Black Magic: White Hollywood and African American Culture (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2004).

[5] Ruth Vasey, The World According to Hollywood, 1918-1939 (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 12.

[6] Douglas Brode, Denzel Washington: His Films and Career (Secaucus, NJ: Carol Publishing, 1997), 73.

[7] John H McWhorter, Losing the Race: Self-Sabotage in Black America (New York: The Free Press, 2000), 108.

[8] bell hooks, Reel to Real: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies (New York: Routledge, 1996), 85.