Sex and the City: a Festival Introduction

by Roger Rawlings

The Savannah Film Festival is beloved because it comes immediately after the Toronto and New York Film Festivals, showcasing the end-of-year films that are likely to be in the news in the coming awards season; it has often included the Best Picture winner of that year; and, it is slipped into a smallish town in the South, making the whole affair manageable (unlike, say, the madness of Sundance). Best of all, it is an event that truly brings the town together.

The Savannah Film Festival is beloved because it comes immediately after the Toronto and New York Film Festivals, showcasing the end-of-year films that are likely to be in the news in the coming awards season; it has often included the Best Picture winner of that year; and, it is slipped into a smallish town in the South, making the whole affair manageable (unlike, say, the madness of Sundance). Best of all, it is an event that truly brings the town together.

As always, this year the community was eminently gracious to the films and the artists, even when the films postulated wild avant-garde experimentation, severe social criticism, controversial political stances and dangerous examples of lives lived on the edge. But they were also extra patient this year as the festival pushed the envelope with a lot of provocative S.E.X.

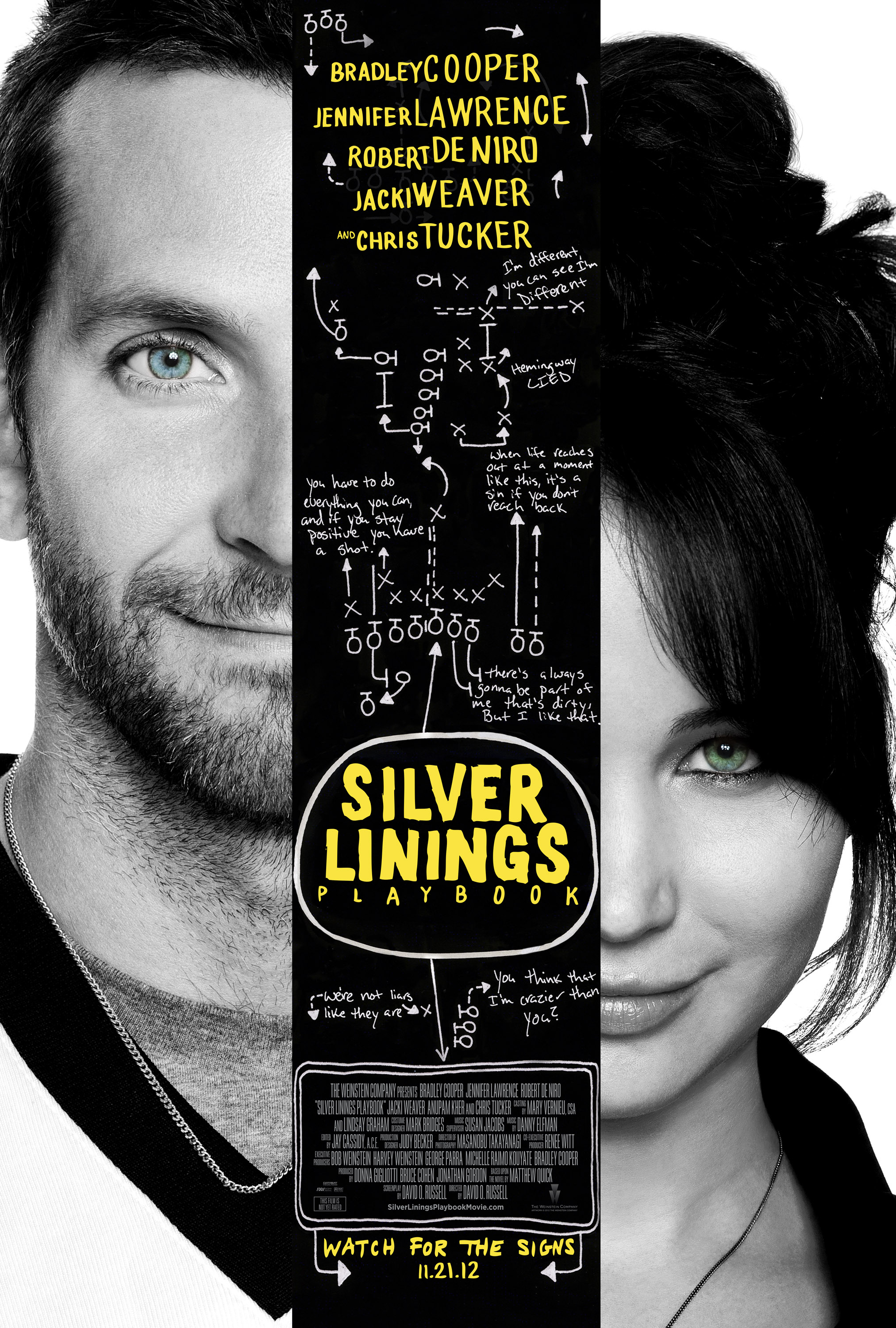

The Cinema Studies panel tries to spot trends and themes of these films, and this year it noticed that many films seemed to concern a chronic “wounded masculinity.” Films such as Flight, Rust and Bone, Violet and Daisy, On the Road, and Silver Linings Playbook presented males whose identities as able bodied everyday heroes was challenged in multiple ways, creating confused and downward-spiraling characters (even Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master fell into this category, a film released only a few weeks earlier than the festival).

What may be the cause of such a trend? Certainly one answer would be the down economy. After years of pain and hardship for many middle- and working-class American families, as was true during the Great Depression, male identity is intrinsically inter-woven with one’s profession. With so many Americans out of work since 2008, masculinity most definitely has been in crisis. But instead of “hitting the road” or “bucking up” to face down the hardships, this recession’s wounded males must now go to therapy and imbibe psycho-pharmacological drugs to “cure” their problems. Conflict now comes from having a “condition” that must be diagnosed and treated from the outside; introspection never just comes from within anymore.

Taken even further, though, a more prominent theme might be, “Dads attempting to reconcile with their sons.” All the nightly special features had some version of this narrative—Flight, Rust and Bone, On the Road, and of course, Silver Linings—which is important because these are going to be the most influential films to come out of the culture industries in the next two months. Ultimately, Denzel Washington (Flight) must face his demons if he wants to have a real relationship with his estranged son; in Rust and Bone, Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts) must come to terms with what adulthood really means when his son Sam has a terrible accident through borderline negligence; Kerouac’s On The Road was always about Neal Cassidy’s search for his missing father in the postwar Northwest; and, so, Silver Linings has Bradley Cooper inheriting his father’s (Robert de Niro) Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (all of his decisions are based on hunches and coincidences), putting truth to the edicts “the sins of the father…,” and “the past is never dead; it isn’t even past.”

Dysfunctional families in American film have been a staple ever since Ordinary People, ever, even, since Stella Dallas. At least now, though, we can have a laugh about it all, instead of it always having to be expressed through misty-eyed melodrama. This year, thankfully, we were also spared the “cute” kids telling us how precious it all is (Little Miss Sunshine, The Family Stone, The Squid and the Whale, Another Happy Day; although, this year did bring those darlings in Wes Anderson’s Moonrise Kingdom!). Because of its gently mocking tone of melodrama’s preciousness and precociousness, Silver Linings was the most successful of the festival films to illustrate these ideas.

After the Silver Linings screening, friends were quick to dismiss it: “It was a mess! What was that? It seemed lost!” (These are the same folks who rushed to hail Amour as “A masterpiece!” Amour is an incredible piece of European art filmmaking, probably even a masterpiece—time will tell—but one couldn’t call it a “great experience.” It is an excruciatingly painful film wherein a bourgeois artistic Parisian family must face the very, very—almost in real time—slow descent of their mother into acute dementia and eventually complete non-motor function, until, finally, relief is given the spent family and, so, the audience. It is a beautiful, serious and daring achievement, but if that’s the new criteria for movie-going enjoyment, paint drying at least has a happier ending).

After the Silver Linings screening, friends were quick to dismiss it: “It was a mess! What was that? It seemed lost!” (These are the same folks who rushed to hail Amour as “A masterpiece!” Amour is an incredible piece of European art filmmaking, probably even a masterpiece—time will tell—but one couldn’t call it a “great experience.” It is an excruciatingly painful film wherein a bourgeois artistic Parisian family must face the very, very—almost in real time—slow descent of their mother into acute dementia and eventually complete non-motor function, until, finally, relief is given the spent family and, so, the audience. It is a beautiful, serious and daring achievement, but if that’s the new criteria for movie-going enjoyment, paint drying at least has a happier ending).

But if Silver Linings is a mess, what’s wrong with that? This is a story (from the 2008 book by Matthew Quick) about two very messed-up individuals who find each other as a result of marital traumas (he attacks his wife’s lover; she loses her husband unexpectedly and they both go into tailspins). Okay, so they’re messed up? If they are “messed up,” isn’t content supposed to be form? Their messiness is illustrated by the jump cut editing and anxious hand-held shooting style, enhancing their fractured psyches.

Looking closer, though, Silver Linings Playbook isn’t a mess at all. It is a hermetically-sealed airtight classical three act structure: Act 1) how they both fall apart; 2) their meeting-cute, and then warming to one another; 3) and then, the ballroom dancing challenge. It is quite a conventional Hollywood narrative, which makes sense given David O. Russell’s roller coaster career; for all his Existential bravado (I Heart Huckabees), he’s wise to now stick somewhat to the Hollywood formula (The Fighter). The classical story has merely been updated for our 21st century age of Xanax and shrinkage. Most of all, Silver Linings was especially refreshing in a field of films that were all rife with sex, because it was the only evening film that didn’t have any!

Rust and Bone allowed audiences to witness the sex lives of those who went through physical horrors, cleverly CGI-ing Marion Cotillard’s altered body; On the Road, as a fiercely faithful adaptation of the Kerouac novel, captured the early Beats’ restless search for experience through running away, palling around and talking about or having sex at every opportunity; in Violet and Daisy sex is an act of revenge against societal gerrymandered gender roles; and Flight, whose lead character (Denzel Washington) uses sex as a by-product of his nihilistic self-loathing, offers sex literally “in-your-face” in its we-get-the-point overlong opening scene. And then there’s the embarrassingly silly (for everyone involved) FDR film, Hyde Park on the Hudson, which turns the 32nd president into a David Duchovney-type sex addict.

But, one might argue, sex is always in the culture (even generals in the military apparently indulge). And since movies are there to reflect the culture, this should not be such a charged issue. True. But, every night the sex was flagrant and incessant, often prurient and gratuitous, and what made Silver Linings much more fun was its refusal of the obvious: it handled the sex angle with symbolic grace and charm by allowing ballroom dancing to stand-in for sex.

The dysfunctional leads (new A-listers Bradley Cooper and Jennifer Lawrence) make a pact: that he will agree to dance with her if she will get his apology note to his ex-wife (her sister in law). They practice throughout Act 2, and in the last act they show the judges, and us, their clearly self-invented moves. They aren’t terrible, but are merely semi-good, making it all the more humorous, “climaxing” in the hilarious crotch-in-the-face ice capades lift. This is their awkward sex scene that the audience has been anticipating for the last 75 minutes, much as the rapid-fire dialogue of the 1930s screwball comedies stood in for sex in the face of the Production Code. If the two damaged dysfunctionals must try to “manage” their anger in the new “cure-your-ailment” society, dancing as sex is a pretty fair and classy swap. And, it is the ultimate excuse for the different families, friends and enemies to come together, a stand-in for the community at the movies and at the film festival itself. A heterogeneous block-party be-in Lovefest.

If the thing about the Savannah Film festival is its John Fordian “bringing the community together” vibe—when was the last time you saw a comedy with a sold out house, everybody laughing along together?—then Silver Linings gave it its church choir sing-along gospel rapture. Maybe Silver Linings isn’t Noises Off or His Gal Friday. But it is vibrant, it moves, and it speaks to the collective inclusive ideal of the diverse American community, a wonderful collective sigh of dysfunctional relief. So, see it with your community, with a packed house if possible on a Friday night; you’ll laugh, you’ll cry, together, just as the (Mad) Man said.

Published December 3, 2012.

Roger Rawlings is Professor and Program Coordinator of Graduate Cinema Studies at the Savannah College of Art and Design. His Ph. D in English and Film Studies is from The Graduate Center of the City University of New York and Masters in Cinema Studies from New York University. Roger has produced several films, including Headwrecker in Ireland, which won the Irish Academy Award for Best Short Film, 2002. He co-wrote and directed the feature, Neurotica (2004), starring Amy Sedaris and Brian D’Arcy James. Most recently he co- wrote the story and Executive Produced the forthcoming feature Losers Take All, to be released April 2013.