Jean Ma

Close reading: The Mise-en-scène of Song Performance

A question frequently raised in recent discussions of the field of Chinese cinema is whether close analysis necessarily privileges certain realms of filmmaking over others. Perusing the titles of English-language publications on this topic, one immediately notices the preponderance of close readings of films from the last three decades – a period that witnesses unprecedented global visibility for filmmakers from Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the PRC, in the realms of art cinema, commercial genre cinema, and artistic/political underground movements. Against this contemporary bias, a sense of urgency has arisen around Chinese cinema as a history yet to be fully written, marked by gaps in time (i.e., the “missing years” of the Cold War period) as well as in entire sectors of production (i.e., dialect industries like Amoy and Cantonese). The ongoing endeavor to construct a basic historical foundation animates tensions between the close and distant view, between approaches that dive deep into the individual film and those that open outward towards broader vistas of production, distribution, and reception. To the eyes of some critics, historically grounded inquiry necessitates a shift in interpretive scale, away from close analysis to the long view; for example, in his important study of the Amoy film industry, Jeremy Taylor posits a fundamental incompatibility between these methodologies.1

But in my own work I have found the opposite to be true: film form carries an artifactual significance, as much as an aesthetic or stylistic meaning, and the work of close analysis is dissociable from the historian’s task of thick description. Thinking historically cannot only mean turning away from the illusory world within the film towards the empirical conditions surrounding it; rather, it must entail a confrontation with the individual work as a relic of its time.

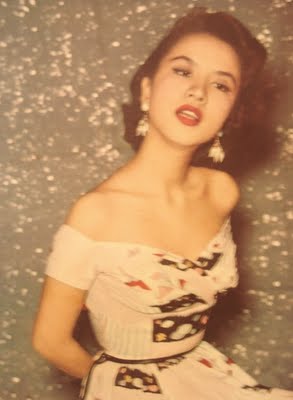

By way of a more concrete illustration, I offer an example from my current book project on the songstress in 1950s and 60s Mandarin films from Hong Kong. Scenes of song performance, always by female vocalists, were ubiquitous in this period, attesting to the tight symbiotic interconnections between the film and music recording industries. One of the biggest singing stars of postwar Hong Kong was Chung Ching. Her first starring role came in 1956 with Songs of the Peach Blossom River, where she played a plucky country lass nicknamed Wildcat, with a lovely voice and fondness for singing. Wildcat meets a visitor from the city, Li Ming, who is interested in her talents and invites her to his home to record her singing. In the scene that follows, we see Wildcat singing into a microphone; the camera tracks back to a long shot that reveals Li sitting to her right, looking on with delight while he operates a magnetic tape recorder. The sound of her voice continues over a dissolve into a medium close-up of Li. The camera then pans back over to Wildcat staring at the device in wonder as her song is played back to her. The temporal interval between the actions of recording and replaying is elided in the sonic construction of the scene, for the song continues without interruption as the film shifts from one point in time to a later point. Contained in the scene is an ellipsis in time that is visually registered but sonically denied – an inaudible cut, we might call it, designed to impress upon the audience the virtual identity between the live and technologically mediated voice.2

Though it passes in the blink of an eye, this inaudible cut holds a key to unpacking the logic behind song performance on film in this period. To begin with, in Wildcat’s uncanny confrontation with her recorded voice, we are offered a momentary glimpse into the workings of playback technology. Sound design in this period depended primarily upon post-production processes, with playback technology utilized in the construction of song sequences. Actors would move their lips in sync with songs prerecorded in a studio. The synthesis of sound and image at the end of this process amounts to a technological re-integration of these two separate registers. But if the voice breaks free of the singer’s body at the moment when Wildcat becomes her own listener, it is only to demonstrate that it never really belonged to this body in the first place; the lack of any audible difference between the “live” and recorded performance of the song retroactively reveals liveness itself to be an effect of mediation. On the basis of this opening of a fissure between body and voice, we can begin to draw out the particular terms of the audiovisual contract that Songs of the Peach Blossom River holds out to its audience.3

In doing so, we gain a deeper insight into how the relation of body and voice, image and sound, was understood in this period. For this relation does not conform to a standard of synchronization that aims at effectively “[binding] the voice to a body in a unity whose immediacy can only be perceived as given,” in the words of Mary Ann Doane.4 The calculated display of technological prowess here is made at the expense of a necessary, immediate, and self-evident relation of sound and image. No longer the property of the visible body, the voice announces its machinic origins and lays bare the composite nature of song performance as a “trick” of the playback process.

Notably, this disclosure is unaccompanied by any laments for a loss of authenticity, originality, or other such notions of ontological purity. A brief look at a well-known counterexample – taken from a classical Hollywood musical of the same decade – further elucidates this point. Singin’ in the Rain (1952) contains a scene that turns upon a similar revelation of the non-identity of the singer’s voice and body, but with very different implications. In the film’s ending, Lina Lamont, the beautiful leading lady with the ugly voice, is unveiled as a phoney, while Kathy Selden, the owner of the lovely voice that Lina has stolen with the assistance of dubbing technology, is climactically unveiled as the “real star.” The conclusion of Singin’ in the Rain offers a canonical illustration of classical Hollywood cinema’s investment in the voice as a locus of authenticity. The illusion of realness requires the return of the voice to its “original” and rightful source, thereby “perpetuating the image of unity and identity” projected by the performing body. In its insistence on synchronization, Doane argues, classical cinema upholds an ideology of presence while repressing any awareness of “the material heterogeneity of the ‘body’ of the film.”5

Conversely, the lack of anxiety that Songs of the Peach Blossom River displays toward the proper place of the voice reflects a very different set of assumptions about the status of the voice and its relation to the image. This difference is perhaps accounted for by the “no film without a song” mentality of postwar film culture, where musical performance is not limited to certain genres (like the musical), but universally present as part of the basic idiom of narrative cinema. As Rick Altman has pointed out, the Hollywood musical pushes film’s constitutive material heterogeneity to a limit, insofar as “more than any other type of film the musical has resorted to dubbing, rerecording, hopping, postsynchronization, and other techniques which involve separate recording of the image and diegetic music.”6 Whereas Singin’ in the Rain stands out as the exception that proves classical cinema’s rule, the far-reaching scope of musical spectacle in Hong Kong cinema renders the composite and fragmented nature of film performance inescapable, a normal condition hardly meriting the work of repression.

Indeed the high premium placed on musical spectacle within this film culture trumps not just representational ideals of identity and unity (revealing the historical and cultural contingency of such ideals along the way), but also the actual capacities of the performer, as demonstrated by Chung Ching’s examples. For if Chung was typecast as a songstress for the better part of her career, this was in spite of her lack of vocal talent. Chung’s song scenes were always dubbed by other vocalists. This did not prevent her from building a successful and prolific career as a singing star, appearing in numerous productions each packed with interludes of song performance. Songs of the Peach Blossom River marked the beginning of an enduring partnership between Chung and the singer Yao Lee, celebrated as the “queen of Mandarin pop”; the two would collaborate in a similar fashion in many subsequent productions, with Yao providing the vocals for Chung’s musical scenes. The film’s program brochure even features an image of Yao on its cover, attesting to the drawing power wielded by the singer despite her behind-the-scenes role. As this marketing maneuver suggests, Yao’s star power equaled or exceeded that of the many actresses whose song performances she dubbed; although she rarely appeared onscreen, hers was one of the most recognizable voices of postwar popular music.

Yao Lee’s visibility here stands in stark contrast to the anonymity imposed upon those who play a similar behind-the-screen role in other contexts (as illustrated by the travails of the fictional Kathy Selden). In postwar Hong Kong many other well-known actresses relied on professional vocalists to dub their songs, and even in the case of singers who fell somewhat short of Yao’s star power, the practice of substituting singing was no secret to the public. The names of behind-the-screen singers were regularly included in film credits or sometimes even, as in Yao’s case, billed above those of the actors. Film songs were circulated and sold as LPs that prominently featured the names and faces of vocalists on their covers, as well as disseminated in print as song sheets that further endowed this music with a life beyond the film. Moreover, far from being unique in its approach to film music, Songs of the Peach Blossom River finds a precedent as far back as the early sound era. The first full-sound Chinese film Songstress Red Peony (1931) paired the image of movie queen Hu Die with the voice of the male opera singer Mei Lanfang, famed for his performances of female roles in Beijing opera.

The asynchrony of body and voice in Songs of the Peach Blossom River maps onto the separate identities of the two performers who collaborate in this scene, attesting to a composite – rather than unified – conception of stardom operative in this period.7 A brief moment in which sound and image split off from one another points to Hong Kong cinema’s cross-medial ties to a larger cultural universe of popular songs and musical performance (a universe referenced in the film’s plot when Wildcat is eventually discovered, her songs played on the radio and performed by her on stage). These ties are activated in the scene of song performance, which weaves together the pleasures of cinematic storytelling with those of musical listening by means of an interplay of voices and bodies.

Jean Ma is an Associate Professor in the Department of Art at Stanford University. She is the author of Melancholy Drift: Marking Time in Chinese Cinema. She is the coeditor of Still Moving: Between Cinema and Photography (with Karen Beckman), and a forthcoming special issue of the Journal of Chinese Cinemas on sound and music. Her work has appeared in Grey Room, Post Script, Journal of Chinese Cinemas, A Companion to Michael Haneke, and Global Art Cinemas: New Histories and Theories.

————————————————————————-

1 Rethinking Transnational Chinese Cinemas: The Amoy-Dialect Film Industry in Cold War Asia (New York: Routledge, 2011).

2 My description of this as an “inaudible cut” is inspired by the technique of the invisible cut, associated with the trick films of George Méliès.

3 The idea of the audiovisual contact comes from Michel Chion, who defines it as “a sort of symbolic pact to which the audio-spectator agrees when she or he considers the elements of sound and image to be participating in one and the same entity or world.” Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen, ed. and trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 222.

4 Mary Ann Doane, “The Voice in the Cinema: The Articulation of Body and Space,” Yale French Studies 60 (1980): 47.

5 Doane, “The Voice in the Cinema,” 47.

6 Rick Altman, The American Film Musical (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1978), 64.

7 Here we encounter a parallel between song performances in Chinese and Indian cinema. As Neepa Majumdar writes, “Hindi cinema’s song sequences simultaneously draw upon two different star texts, those of the sing and of the actor. Putting together the ideal voice with the ideal body results in an ideal cinematic construct, a composite star.” Wanted Cultured Ladies Only! Female Stardom and Cinema in India, 1930s – 1950s (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), 177.