Adrian Martin

Hands Across the Table

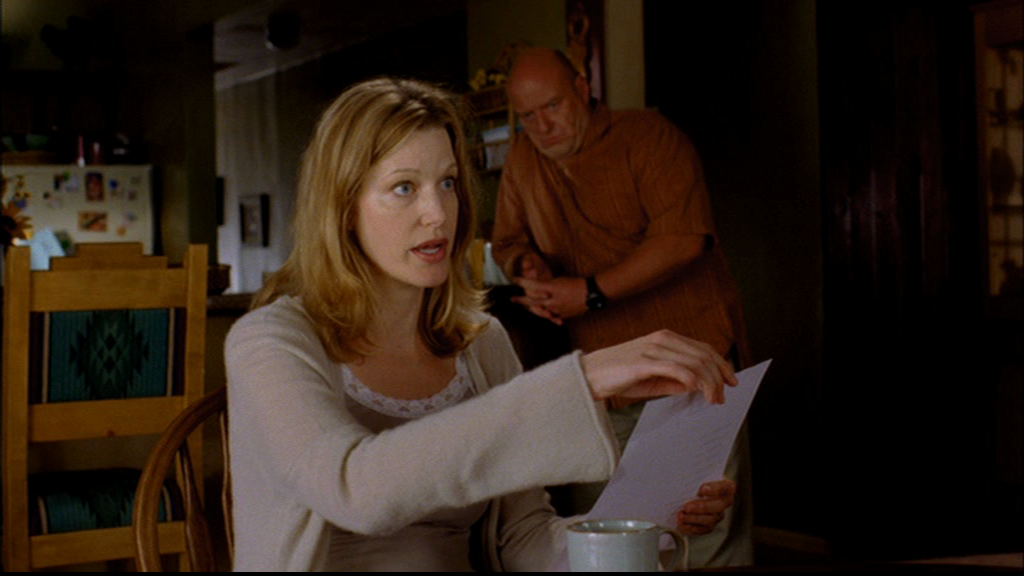

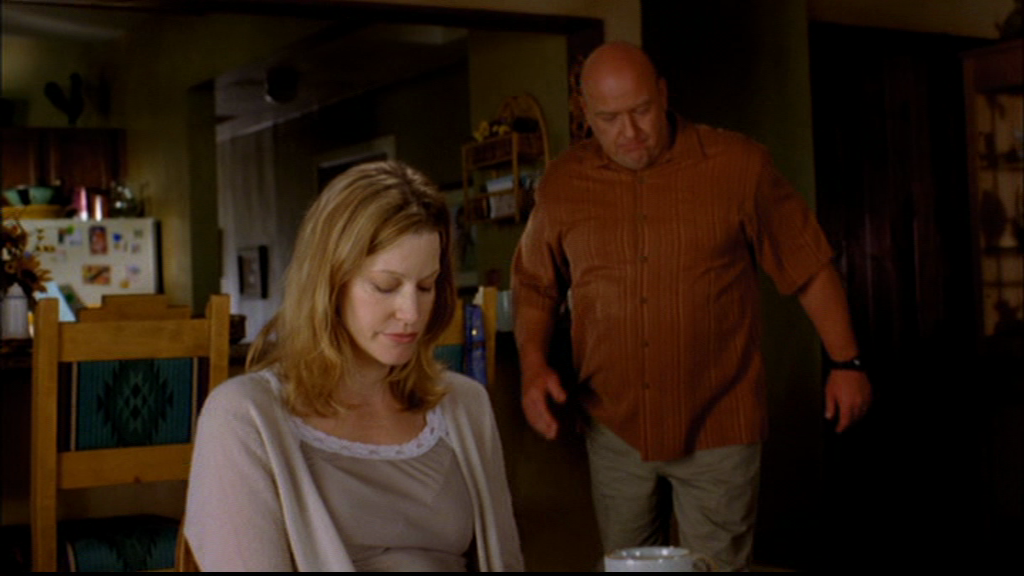

Hank (Dean Norris), a top guy in the US Drug Enforcement Agency, is standing, at a noticeably large distance, behind his confused and upset sister-in-law, Skyler (Anna Gunn) – who is seated, conversing with her son, Walter Jr. (R.J. Mitte) and a detective. Her husband, Walter (Bryan Cranston) has gone missing, and she’s worried, panicking over this mystery. After several minutes of group discussion, Hank waddles forward, perhaps reluctantly but nonetheless stoically, to offer Skyler some small, physical solace – not a hug, but rather a slightly manic ‘it’s alright’ pat on her shoulder. A cut takes us right around from his stiff, even pained, walking approach, to – in the foreground of the frame – his hand gesture on her body, seen now from behind Skyler’s chair. Why emphasise this detail via such a cut and shift in camera position, around eight and a half minutes into “Grilled,” the second episode of Season 2 of Breaking Bad (2009), directed by Charles Haid?

I name the director, respectfully (because this is an especially rich and wonderful episode of Breaking Bad) – but in full awareness of the difficulty of attributing the precision and point of this cut to him, or at any rate to him alone. Two – probably more than two – key figures in the production could well have been part of making this decision: the Creator/Producer of the series, Vince Gilligan, who oversees everything in every episode; and the Director of Photography, Michael Slovis, who presumably played a huge role in setting the look and tone of the entire opus (he later directed some episodes).

So let’s bracket the thorny auteur attribution and look at the scene itself. Long-form television fiction has, over the past few decades and particularly in a series as good as Breaking Bad, returned us to a special item of narrative craft: what narratologists such as David Bordwell call motivation, which refers to the way that plot actions performed by characters are rendered natural and logical, within the fictional world, by being associated with specific psychological traits. In something that goes for five or more seasons – and where the basic narrative arc has been sketched well in advance – there arises the opportunity to plant certain motivating moments (perhaps more than once, as required by the needs of the fiction) long before they are paid off in specific plot actions.

Many hours later in screen time – and three years later for viewers who followed the initial prime-time roll-out of the series – Season 5 of Breaking Bad will need to make absolutely believable, not just once but twice over, the action of Hank excusing himself from talking to his troubled brother-in-law, the previously missing Walter, leaving the room to take a breather (on the pretext of making coffee) – and thus inadvertently allowing Walter to plant (and eventually remove) a secret, illegal listening device. How can a viewer be persuaded to accept this potentially risible event? We have to know – consciously or not, on the basis of our experience of what we have already seen and heard in the series – that Hank is so ill-at-ease with displays of strong emotion from others (even his immediate family members) that he will do anything, or rather do something quite specific, to avoid direct contact with this emotion. Hank deals with it, but reluctantly, awkwardly, badly. And that is why, in Episode 2 of Season 2, his shoulder-pat is underlined – quietly, but definitely. It goes into our spectator-memory and eases through the much later plot contrivance (understanding, of course, that every single plot move in the universe of fiction is, in this sense, contrived, manufactured, manoeuvred into place).

The more you look at this entire, almost three-minute scene, the better and more intricate it gets. We can notice, for example, that Hank does his patting gesture, in fact, a grand total of four times: on the detective, on Walter Jr, and twice on Skyler! This is contrasted with the warmer mother-son embrace, viewed from the master-shot’s distance, that sneaks into the final frames of the scene. (Keen students of style analysis may recall here Victor Perkins’ wonderful analysis of a related gesture of sociality that circulates through a scene in Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place, 1950; or the various studies in Andrew Klevan’s book Film Performance.)

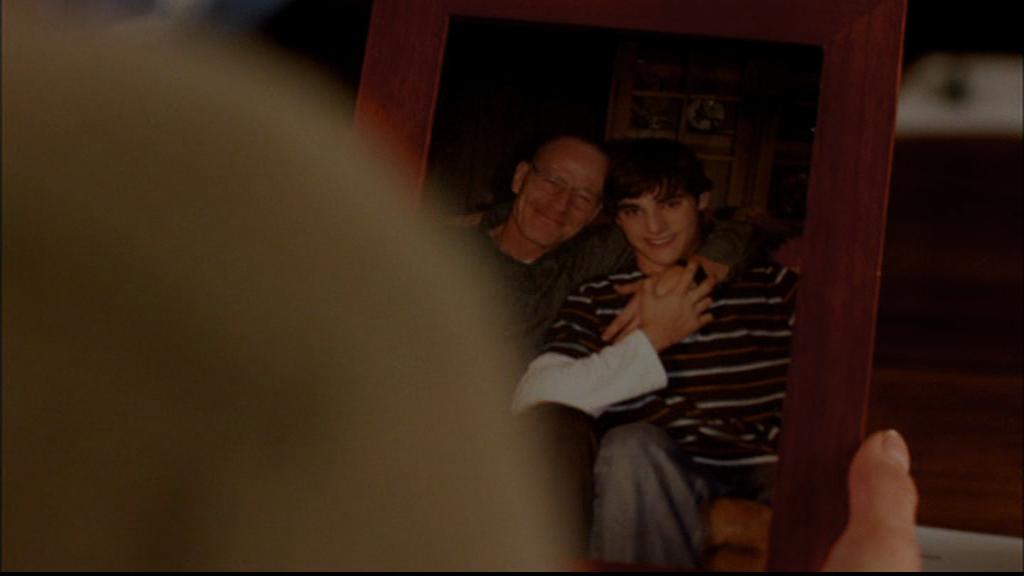

The scene even begins (before the first master-shot set-up) with some hand business, in the father-and-son photo which Skyler offers to the detective – a case of motivation in the very different sense that Alain Masson, in his study of a scene from Billy Wilder’s Avanti! (1972), gives this term: the ingenious transformation of even the most banal, ordinary objects and gestures into meaningful motifs that thread through the work as a whole (a very big whole, in the instance of Breaking Bad):

We can notice, too, an intriguing distribution of gestures and comportments along the line of gender: all three men in the scene are visibly uncomfortable in the face of Sklyer’s ‘feminine’, histrionic distress (look again at the third and fourth frame-grabs above) – they may all be thinking that she is deluded, barking up the wrong tree when it comes to the interpretation of her husband’s odd behaviour – and they each show this in a particular, specific way: Walter Jr plays neurotically with his hands, while the detective, in an extremely odd (but obviously deliberate, directed) gesture-system, clicks his head, rigidly and in sequence, into three (and only three) positions: awkwardly leaning it back to look at Hank, straight ahead to take in (with evident incredulity) Skyler, and right down to his pad to take notes (and to avoid female emotion). Which is to say: gestures in a mise-en-scène usually have a lot to do with prevailing but internally dynamic social codes (in a given, specific society and situation) concerning what is acceptable and unacceptable in terms of bodily behaviour and interaction, the limits and transgressions of interpersonal space. This is what I have elsewhere called social mise-en-scène, a missing ingredient in much stylistic/formal analysis past and present.

There are doubtless some conventional, predictable aspects to the televisual mise-en-scène and découpage of the scene. There is, first, a high level of shot repetition, or what film theorists call redundancy: ten separate camera positions (or set-ups), distributed over thirty-eight cuts. (When close analysts count shots as defined by discrete cuts, as they have long been trained to do, they almost always forget to attend to the plan of the set-ups, which is the first phase of the eventual, fully edited découpage; this range of positions from which a scene is covered is far more important, on the practical, decision-making level, to filmmakers themselves than the number of eventual cuts, which is always a highly variable factor.) Second, a tendency to over-use the slightly shaky, hand-held effect (in almost every set-up here) so beloved of TV drama – something that comes from the dual pressure of shooting quickly and wanting, at any cost, the ersatz realism of a ‘you are there’ aura. And third, a massive concentration of the all-inclusive, wide-scale master-shot, which here comes in two versions: a darkly lit variation at the very start and end, showing us Hank’s entrance and eventual exit; and the more traditional, well-lit three-shot showing us Skyler, Walt Jr. and the detective seated, conversing at the table.

Some analysts may also find conventional the way that the cuts are, by and large, geared to, or cued by, either mid-gesture overlaps (her hand passes a document/his hand receives it), or exchanges of glances. But here, we begin to enter a more fine-grain area, where variations and subtleties can be introduced – as they often are in the carefully and impressively directed/assembled episodes of Breaking Bad. And our example is a good one for this inquiry: the detail on Hank’s hand gesture is surely more than a simple, functional ‘cut on movement’.

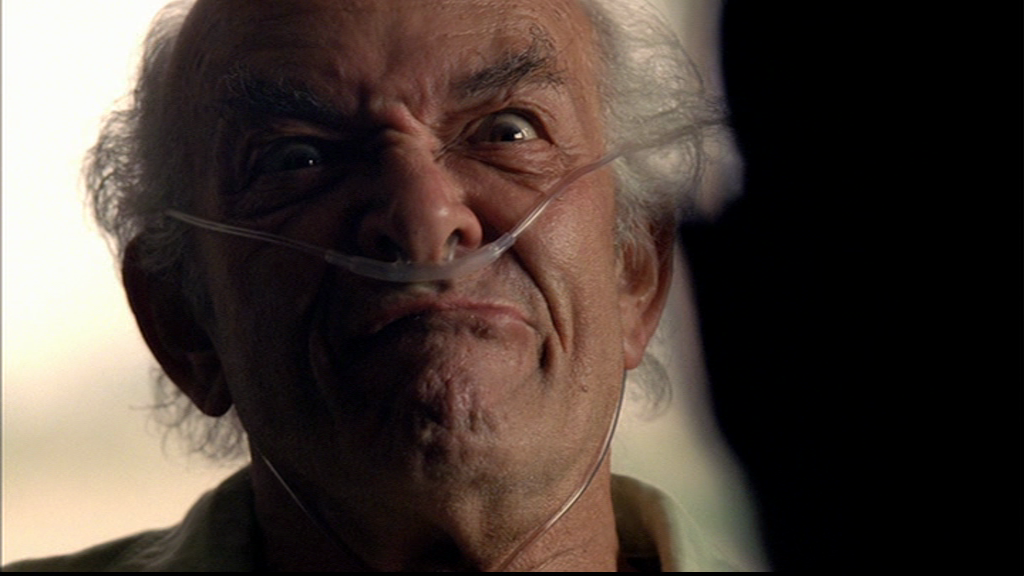

One especially significant decision stands out in this scene: Hank does not sit at the table with the other three. He takes up his – quite deliberately awkward – standing/leaning position behind Skyler. Why? First, it’s his problem with the emotions of others that I have already discussed: an avoidance tactic. But it’s also, second, a power-ploy: by taking up this indirect stance, he is able to make significant eye-contact with the detective, an exchange that Skyler cannot see. Several major plots in Breaking Bad – especially all the tense events circulating around the mute, disabled figure of the (nonetheless) all-seeing and all-knowing Hector (Mark Margolis) – hinge on the issue of unseen looks and returned gazes.

Two final things. Frequently, when I offer the public demonstration of an analysis like this one, I am asked whether I am perhaps ‘reading too much in’ to the scene, over-interpreting it – seeing things that the makers them-selves would never have thought of planting in the design of their work. Chance and coincidence play a big role in filmmaking (so the objection goes), and not all of this kind of stuff is systematically, consciously previewed or conceptualised. This may sometimes be so. However, I prefer to put my faith in the power of artistic intuition – always more powerful and far-reaching than prefigured plans – and then on the capacity for seizing upon and working through the material that has been gathered, making it into a satisfying, coherent whole (“shaping a whole piece of entertainment”, as Nicholas Ray used to say).

Was it the episode Editor, Skip MacDonald, who seized upon the full significance of Hank’s hand detail, as covered (twice) in the set-ups, choosing to underline it with a cut? We’ll likely never know, but the important thing is: it’s there.

Moreover, analysis of the particular sort I have here exemplified is not at all interpretation in the strict sense – it has nothing to do with symbolism, metaphor, allegory, etc. It doesn’t even (yet) work up to a properly thematic reading of Breaking Bad. Insofar as it presumes to decipher the craft of the series, it sticks close to the idea that Victor Perkins expressed so well over twenty years ago: that the meanings of a scene are directly there on the screen – not somehow under it, or behind it. These meanings may need to be teased out to be explicated and cohered into a pattern that becomes fully graspable – but they were never invisible, never obscure in the first place.

Lastly: I try to keep an eye and ear out (as Masson wisely advises) for the details that escape the grid of my own, neat analysis. It is, often, these very details which give the fullness and complexity of life to a scene, and to the work as a whole. In this case, my moment choisi has a kick-back coda: just as Hank is about to swiftly withdraw his hand from Skyler’s back, she grabs it for a little extra warmth, and holds on for dear life, almost falling out the image as she does so. This little drama of social mise-en-scène and resistance happens right at the edge of the frame. And that – big screen or small screen, it makes no difference – is cinema.

REFERENCES

David Bordwell, Narration in the Fiction Film (University of Wisconsin Press, 1985).

Andrew Klevan, Film Performance: From Achievement to Appreciation (London: Wallflower Press, 2005).

Adrian Martin, “At Table: The Social Mise en scène of How Green Was My Valley”, Undercurrent, no. 5 (2009), http://www.fipresci.org/undercurrent/issue_0509/ how_green.htm

Alain Masson, “A Sequence from Avanti!”, Continuum, Vol. 5 No. 2 (1992), pp. 167-178.

V.F. Perkins, “Must We Say What They Mean? Film Criticism and Interpretation”, Movie, no. 34/35 (1990), pp. 1-7.

V.F. Perkins, “Moments of Choice”, Rouge, no. 9 (2006), http://www.rouge.com.au/9/moments_choice.html

© Adrian Martin April 2013

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Adrian Martin is Visting Guest Professor of Film Studies at Goethe University, Frankfurt, during 2013/4. He is the Co-editor of LOLA (www.lolajournal.com). His most recent book is Last Day Every Day (Punctum).